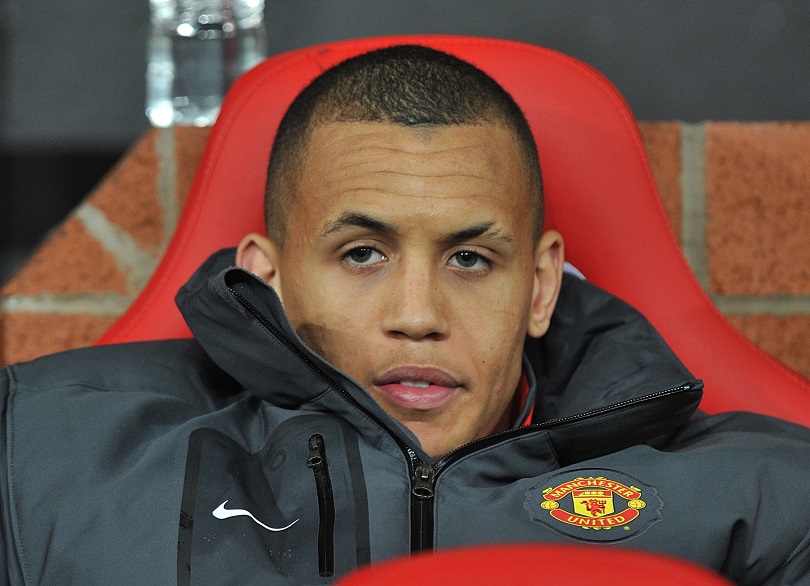

Where on earth did it all go wrong for Ravel Morrison?

In 2011, Ravel Morrison was the star of a Youth Cup-winning Manchester United outfit that featured Paul Pogba. So how come the Frenchman is now worth £90m, while his ex-teammate's in the Championship?

Gary Neville chose a timely moment to learn the ropes in television. While he was still a player, the right-back commentated for MUTV in the 2010/11 season, climbing up a rickety ladder at Altrincham’s Moss Lane ground or into the Old Trafford gantry to watch youth-team and reserve matches. Manchester United’s junior side, featuring Paul Pogba and Jesse Lingard, shone, with one player especially sticking out.

“Ravel Morrison’s ability was just a scandal,” Neville tells FourFourTwo. “He was playing in a midfield three with Pogba and Ryan Tunnicliffe. All of them were outstanding, but Ravel was the principal game changer. He was an unbelievable talent, a Paul Gascoigne-type who could beat men and score some incredible goals. There are few players in central midfield who can beat people – Ravel could drift past them.”

United midfield legend Paddy Crerand is prepared to go even further than Neville in his assessment of Morrison’s potential. “Ravel was the best youngster I’d seen since George Best,” he gushes. This is based on seeing almost every game Morrison played for United youth and reserve teams while working for MUTV. “Even in a side with Pogba, Ravel stood out. He was fast and had a quick football brain – everything a big star should have.”

Paul McGuinness worked extensively with Morrison when he was the youth coach at United, a position that he held for 23 years until 2016. “Ravel has the quality that the very best players possess – timing,” he tells FFT. “He has the ability to keep the ball until just the right moment to play the pass through the opposition’s defence, or to entice some defenders in and then slip right past them.”

Pogba in his shadow

United won 6-3 on aggregate with Morrison exceptional, bagging a brace in a 4-1 second-leg victory at Old Trafford

After a particularly tough 2010/11 FA Youth Cup run which saw them eliminate some top teams, including Liverpool and Chelsea, United met Sheffield United in the two-legged final. The side from Manchester won 6-3 on aggregate with Morrison exceptional, bagging a brace in a 4-1 second-leg victory at Old Trafford. It meant a record 10th FA Youth Cup for United, with Tunnicliffe, Lingard, Pogba and Morrison all pictured with the trophy. They were making some waves.

“Ravel Morrison was younger than me but he was brought up to train with us,” said Blackburn Rovers defender Corry Evans, then with United. “You could see his ability – he was effortless as he glided past players and could shoot and score with either foot.”

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Pogba and Morrison were the first to be given a chance with the first team, the latter making a cameo in a 2010 League Cup Fourth Round victory over Wolves, but neither would make the crucial breakthrough. Both ended up in Italy. Pogba became one of the most sought-after players in world football. Morrison did not.

Born in Wythenshawe in February 1993, Morrison didn't grow up on the vast 1930s council estate near Manchester airport which takes the same name, but rather in the upper working class/lower middle class region of west Manchester, in between Old Trafford and the Carrington training ground. United spotted Morrison while playing for Fletcher Moss Rangers, which picks up some of the best young Mancunian talents, but as Morrison progressed through the Red Devils’ ranks, his behaviour and outside influences were becoming an issue.

United felt they’d done as much as they could and given him chance after chance. They had supported him even after he was convicted of intimidating a witness to a knifepoint robbery, for which he’d escaped with a 12-month referral order and was instructed to cough up £2,000 in compensation. And they also backed him after he admitted criminal damage, having thrown his partner’s phone from her parents’ window. Morrison was referred to Salford’s youth offending team for domestic violence counselling, and then fined again.

Fergie's best

Others at Old Trafford insist that if Morrison was 10 per cent less talented, his behaviour would have seen him thrown out of football by the time he hit 16

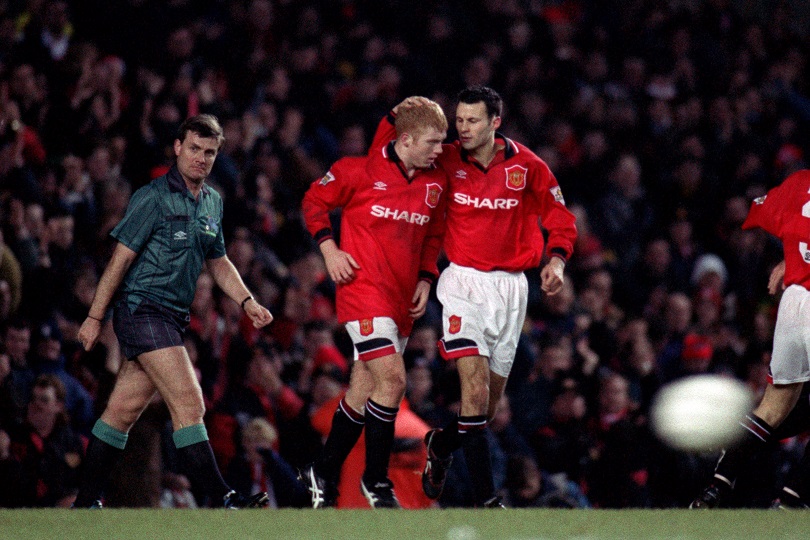

United had a vested interest. Alex Ferguson told senior players that Morrison was the biggest talent he had seen at United at the age of 14. Better than Paul Scholes, better than Ryan Giggs. Others at Old Trafford insist that if Morrison was 10 per cent less talented, his behaviour would have seen him thrown out of football by the time he hit 16.

But Ferguson persisted. He even moved him to the first-team dressing room, but the senior players soon became exasperated with the errant youngster. How could someone so talented, they thought, be at fault so often? Why was he always in the wrong place at the wrong time with the wrong crowd?

They’d all made the necessary sacrifices to become a professional footballer and they’d reached the very top. The rewards were there for Morrison to see every day – the status, respect and accoutrements of wealth. It frustrated them even more that someone with such natural talent appeared to be throwing it all away.

Morrison has been portrayed as a thick thug, but those who know him well insist that is not the case. His intelligence extends beyond what he can do with a football, but circumstances in his life haven’t helped him.

People hold back when they’re talking about Morrison. He turned 24 in February but his career is still alive and they don’t want to damage his prospects. He is not the bore sitting at the end of the bar saying what could have been. He’s still a professional and people who know him hope he’ll carve a successful career. Many are Mancunians, who’d love him to fulfil his immense talent and believe he just needs a break.

“He was actually a nice lad,” says Crerand, who grew up in Glasgow’s notorious Gorbals. “Quiet and respectful. Sometimes when you grow up with a group of lads, some go astray and you don’t. When you're the one getting a few quid, that can be an issue.”

Personal problems

He comes from an environment where gangs are prevalent and authority is distrusted, where you look after your own if there’s an issue, not call the police

Many have tried to help him. When Morrison played for England U21s, scoring twice against Lithuania in October 2013, boss Gareth Southgate thought he had him on the straight and narrow and hoped that he would soon be playing with the senior team. Roy Hodgson agreed.

There’s a clip of a Morrison goal from one of Southgate’s training sessions which shows his outrageous skill. A cross comes in, and just as he appears ready to volley it, he turns his body and flicks the ball in with the back of his leg – it earned a second round of applause in that session. He scored similar goals at United.

Other coaches in England’s younger age groups who’d experienced Morrison found him more difficult to work with and were reluctant to take him away on three-day trips abroad.

“He’s had deep-rooted issues and you can either point to him and say he doesn’t know how to behave and is at fault,” a United source explains to us, “or you can say he is a by-product of his upbringing, a victim who needs some help and guidance. He thought that things that were socially unacceptable were acceptable. He comes from an environment where gangs are prevalent and authority is distrusted, where you look after your own if there’s an issue, not call the police.”

Ferguson had worked with players from tough backgrounds before, including some of his very best. Although he’d finally said goodbye a year earlier, the Scot didn’t mention Morrison in his second book, published in 2013. He did, however, in his 2015 tome titled Leading.

“Sadly there are examples of players who have similar backgrounds to Giggs or Cristiano Ronaldo who, despite enormous natural talent, just aren’t emotionally or mentally strong enough to overcome the hurts of their childhood and their inner demons,” wrote Ferguson.

“Ravel Morrison might be the saddest case. He possessed as much natural talent as any youngster we ever signed, but he kept getting into trouble. It was painful to sell him to West Ham in January 2012 because he could have been a fantastic player. But, over a period of several years, the problems off the pitch continued to escalate and so we had little option but to cut the cord.”

"That's a genius goal"

As Pogba moved to Juventus in 2012, Allardyce sent Morrison on loan to second-division Birmingham City

Morrison’s transfer fee was £650,000, rising to £2.5 million pending appearances of £25,000 per game. On one level, ample compensation for someone who cost nothing and whose United career amounted to three substitute outings for the first team.

“I hope you can sort him out, because if you can he will be a genius,” Ferguson told then-Hammers manager Sam Allardyce. “He’s a brilliant player,” the Scot said. “Brilliant ability, top-class ability. He needs to get away from Manchester – start a new life.”

“He [Ferguson] let Ravel go for Ravel’s benefit, because he could not see it happening at Manchester United,” said Allardyce. “It was: ‘Get him down there and see if you can get the best out of him, because you’ll have a great player on your hands’.”

As Pogba moved to Juventus in the summer of 2012 after turning down the highest-ever reserve team contract offered to a Red Devil, Allardyce sent Morrison on loan to second-division Birmingham City. Initially it didn't go well, with senior professionals concerned by his timekeeping, but after a showdown with manager Lee Clark he became one of the Midlanders’ star men. Clark was keen for him to stay the following year, but Allardyce wanted him back. Finally, Morrison was taking off in the top flight.

His breathtaking goal in a 3-0 win against Spurs in October 2013 was described like this by Allardyce: “Ravel Morrison picks the ball up in his own half, heads directly for [Jan] Vertonghen and [Michael] Dawson, slips those two like they weren’t there, waits for the keeper to go down – a keeper who’s shown how good he is at one-on-ones, and how quick he is off the line – then uses his outstanding ability to dink it over him. The genius of Ravel Morrison. That is a genius goalfor me. You will struggle to see a better goal than that this season.”

Murky end at West Ham

Morrison claimed he was quickly dropped from the team because he refused to sign with the agent Mark Curtis, who has long had links with many of Allardyce’s players

Morrison was watching his diet, he was well-behaved and he had a professional demeanour. He was the most exciting young Hammer since Joe Cole or Michael Carrick. Then it went wrong and, for once, he doesn’t appear to have been at fault.

Morrison claimed he was quickly dropped from the team because he refused to sign with the agent Mark Curtis, who has long had links with many of Allardyce’s players. Morrison has had several agents or people purporting to represent him. Allardyce denied the claims, but they resurfaced during the investigation that led to him losing his job as England manager after just 67 days.

Fulham put a £4 million bid in for Ravel, which West Ham rejected before complaining to the FA for alleged tapping up – as Morrison’s former youth coach Rene Meulensteen was managing the Cottagers. Regardless, Morrison’s career was, undeservedly, now back in limbo again. When Allardyce left his England post in September, Morrison tweeted: “No 1 listened to a word I said.”

Morrison’s Hammers contract expired in 2015 – he’d spent a part of 2014/15 on loan at Cardiff before Bluebirds manager Russell Slade cut his stay short. His next destination was Lazio, where he was unable to break into the first team and was criticised by coach Stefano Pioli for a lack of professionalism in training and an unwillingness to learn Italian. Lazio are contracted to pay his wages – and collect his fines when he does not show up – through until June 2017.

Last chance saloon?

This January, Morrison trained with Wigan Athletic under Warren Joyce, his former coach at United’s reserve team. “Ravel’s obviously not played a lot of football recently,” Joyce said, “but I know how much of a talent he is from my days at Manchester United. It’s a unique opportunity for us really because we have got a chance to have a look at him and assess his fitness.”

Wigan didn’t push for Morrison, whose wages at Lazio were too high, but QPR did and he chose to join them for a second spell. He had fared well in west London during a 2014 loan, scoring six goals in 17 games.

“I’ve grown up and matured a lot,” Morrison admitted on signing for the west Londoners. “No more messing around – I am focussed and that has been my mindset for the last six months. I’m excited to be given the chance to play football again.”

Many hope he’s right, though they remain cautious.

“He should be a star, that kid,” laments Crerand. “He’s still young and he’s still got time but he’s also wasted time, and if Alex Ferguson couldn’t get the best out of him, who can?”

This feature originally appeared in the April 2017 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!

Andy Mitten has interviewed the likes of Lionel Messi, Eric Cantona, Sir Alex Ferguson and Diego Maradona for FourFourTwo magazine. He also founded and is editor of United We Stand, the Manchester United fanzine, and contributes to a number of publications, including GQ, the BBC and The Athletic.

Join The Club

Join The Club