Remembering Lilleshall: Football’s answer to Hogwarts

St George’s Park it ain’t. So what made the FA’s school of footballing witchcraft and wizardry so special to all who attended? FFT steps inside the chamber of secrets

In a dusty cellar, beneath an early 19th-century hunting lodge in the middle of the Shropshire countryside, sits a little piece of English football history. A discarded honours board, the type you see in cricket clubhouses, is propped against some old cardboard boxes.

On it are the names of 12 full England internationals. All of them, at one time or another, lived in this house. Three other former residents have since won senior England caps, the most recent and almost certainly last being Leon Osman.

In some ways the board is testament to their time here. This is the place Joe Cole “learned so much”; where Jamie Carragher spent the “best two years” of his life and Michael Owen says was the making of him. In fact, speak to any player who attended the FA’s School of Excellence at Lilleshall between 1984 and 1999 and they’ll struggle to find a bad word to say about the place.

But what must ‘the Lilleshall experiment’ have been like for those involved; a bunch of kids from all over the country thrown together miles from home, with dreams of becoming football stars competing with the realities of adolescence? As FFT discovered, these walls have ears…

Cream of the crop

“He was pulling up trees even then,” says one of Owen’s Lilleshall contemporaries. “Some players develop at different rates than others, physically and technically, but it was obvious he was going to make it.” Owen was glowing about his time in Shropshire: “It’s where my game really took off.”

Set up by then-England manager Bobby Robson and the FA’s technical director Charles Hughes, Lilleshall’s aim, according to the governing body, was to give the country’s best 16 footballers in their age group “the opportunity of developing as a selected young talented player in the ideal environment, with the best coaches for a maximum amount of time”.

Each intake was selected via a series of local, regional and national trials, whittled down from around 2,000 until the cream of the country’s finest 14-year-olds were identified, with the ultimate aim of equipping them for international football – should they make it that far.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

In theory, the idea of the best training with the best, coached by the best, was a sound one, but not everybody approved. “I remember Graham Taylor telling me not to go,” says Rod Thomas, who arrived at Lilleshall in 1985 from Watford, where he was already being dubbed ‘the new John Barnes’.

Jamie Carragher, who arrived in 1992, was also under pressure from Liverpool, who feared the National School would “ruin” the “best 14-year-old in the country”. Carra was having none of it. “Lilleshall was the perfect grounding for a young professional,” he later insisted.

But what made it so special to those who attended? It certainly wasn’t a feeling of familiarity. Nestled in the heart of a 30,000-acre site owned for centuries by various ruling classes, Lilleshall Hall couldn’t have been more alien to its newest residents.

"Like a grand old haunted house"

The grounds boast perfectly manicured lawns and hedges, ornate fountains, cloisters, a bowling green and a 70-foot obelisk

“I thought I was arriving at a mansion,” said Carragher. And it’s some mansion. Before you even get to the Grade II listed building the footballers called home, you must enter the estate via the ‘Golden Gates’ – an exact replica of those in front of Buckingham Palace – and negotiate the 1.6-mile drive. Lined with conifers and pines, you wouldn’t be at all surprised if Her Majesty emerged in a Land Rover from one of the many tracks winding off into the surrounding countryside.

“The house itself is exactly like Hogwarts in Harry Potter,” says Danny Webber, who arrived from Manchester United’s youth set-up in 1996. “It’s quite eerie, especially when you’re trying to sleep for the first couple of nights. It’s silent, and when you go outside at night it’s pitch black.”

Rod Thomas agrees: “It’s like a grand old haunted house, with dark corners and creaky doors.” Not to mention sweeping stairways, stained-glass windows, chandeliers, uneven floorboards, bookshelves that could pass for secret passageways and two stags’ heads mounted on the wall in reception (and yes, their eyes do follow you).

The canteen even has decorative faux Roman columns, for goodness’ sake. The grounds, meanwhile, boast perfectly manicured lawns and hedges, ornate fountains, cloisters, a bowling green and a 70-foot obelisk. Obviously. This was as far from the council estates of London, Manchester and Liverpool as you can imagine.

Time for adjustment

Another graduate who was always destined for great things, Cole even told FFT at the time that he had 100% convinction he’d make it in the game. Jamie Carragher recalled one of the coaches telling Cole off for doing a Cruyff turn: “We won’t be having any of that nonsense here, lad!”

No wonder homesickness was a problem. Future Leeds and England striker Alan Smith lasted eight weeks. Owen described the first two months as “an absolute killer… I often cried”. Even happy-go-lucky Londoner Joe Cole struggled at first.

“It was his first outing away from the nest,” his dad, George, tells FourFourTwo. “A couple of times he phoned and I told him: ‘OK, I’m leaving to come up and bring you back’ but 10 minutes later he would ring up again and say, ‘Don’t bother, I’m going to stay’.”

“Some people referred to it as a posh prison,” says Rod Thomas, “because if you had a bad day at training or got told off for doing something you shouldn’t have, it made you feel like you were a million miles away from home, especially in my day when there was no internet or mobile phones. It was sink or swim, basically, and it made you grow up quickly.”

Once that tricky bedding-in period had been negotiated, a hectic schedule ensured the boys had little time to dream of home. Danny Webber explains: “You’d go to school Monday morning, train in the afternoon, train Tuesday morning, school Tuesday afternoon, full day at school on Wednesday followed by training or a game in the evening, school Thursday, school Friday morning, training Friday afternoon.”

Middle of nowhere

Lilleshall gradually established itself as the location of choice for several sports’ governing bodies, with facilities that were – then, at least – state of the art

Any missed lessons would be made up in supervised study periods in the evenings. On Saturdays, the boys would be taken to a top-flight game – “usually one of the Midlands clubs because they were the closest” – before their own game on Sunday morning. Then, if they were lucky, in the afternoon they could get the bus into Telford, the nearest decent-sized town, and go to the cinema. “Boredom?” says Webber. “There wasn’t time.”

Lilleshall wasn’t just plucked from obscurity to house the FA’s Centre of Excellence. At first glance, it might not seem the obvious setting for a famed football finishing school but after opening as a National Recreation Centre in 1951, Lilleshall gradually established itself as the location of choice for several sports’ governing bodies, with facilities that were – then, at least – state of the art.

But it was Alf Ramsey’s England who really put this remote corner of Shropshire on the map when they trained and stayed here ahead of their 1966 World Cup triumph. The fact that it’s in the middle of nowhere… well, that’s kind of the point. There’s literally nothing to do but hone your sporting craft.

But was the quantity of training matched by the quality? One later graduate says it was “miles ahead” of what he was receiving at his club. Earlier students weren’t so sure. “They wanted workhorse athletes; players who could run all day and tackle hard,” one unnamed player tells FFT. Walk along the corridor at the main house lined with graduation photos and you can see what he means: strapping lads with stubble dominate the early years.

Introducing a style

The England hotshot scored five goals in each of his last two trial games, just 24 hours apart, to secure his place at Lilleshall. Then at Charlton, he was also the subject of some unlikely poaching.

“I used to speak to Joe Cole at Lilleshall,” he tells FFT. “He used to say, ‘You should come to West Ham.’” After graduating, he did just that.

“That’s because the prevailing philosophy in English football at the time was about getting the ball forward as quickly as possible,” explains John Cartwright, who was recruited as technical director at Lilleshall in the late ’80s by ‘direct’ football advocate FA technical director Charles Hughes, despite their conflicting coaching philosophies. “We were trying to improve possession football, rotation in positional play and so on, but I was never involved in the selection process,” adds Cartwright.

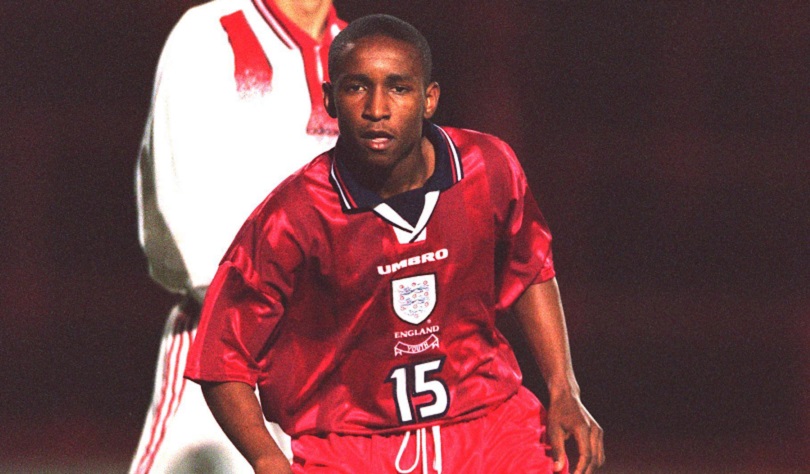

Look at later alumni, though – people like Owen, Cole, Nick Barmby and Jermain Defoe – and the emphasis had shifted. Of the graduates who went on to play for England, the majority were these smaller, more skilful players.

For the first Lilleshall students, that taste of life as a senior international came much earlier. “Other teams would come down and use the facility, including the full England team,” explains Rod Thomas. “We used to train with them sometimes, which was very exciting. I went past Tony Dorigo in a practice match once and I remember him tapping me on the shoulder. His exact words were: ‘Next time you do that, you’ll be sitting on your arse.’ To me, that meant I wasn’t doing too bad.”

Thomas was, indeed, soon brought back down to earth, thanks to the National School’s YTS approach. “You had to do your chores; the jobs you would have had to do at your club,” he recalls. “Cleaning your boots, looking after the balls and kits, cleaning the showers in the changing room. Then there was schoolwork…”

For Lilleshall’s students, like every teenager, getting up for school was a necessary evil – and not always easy. “Without doubt, Joe [Cole] was the slackest at getting out of bed in the morning,” recalls Webber. “We had to tidy our rooms before school, which meant getting up at 6.45 so we could be down for breakfast at 7.30 and on the bus for 7.45.”

No escaping double maths

We had to look out for one another, because we encroached on a normal school where there was a great deal of jealousy

Their destination was Idsall Comprehensive School in the nearby village of Shifnal. Again, it was a world away from what most of them were used to. “Take Cole, for example,” says teacher Barry Fisher, who began at Idsall in 1985, the year after the first Lilleshall intake. “An east London boy in a rural Shropshire school was a complete fish-out-of-water experience.”

Fisher continues: “Actually coming to school five days a week was a shock for a lot of them. The lads from the big cities will tell you that, before coming here, they would often go to school in the morning then bunk off to play football in the afternoon, or they came home after school, dumped their bags and played football until it was dark. Homework was alien to many of them, too.”

So, too, uniforms. “We had to go to school suited and booted,” says Thomas, “whereas at my school in London we didn’t have to wear anything like that.”

With all eyes on ‘the Lilleshall lads’, a pack mentality emerged. “Everyone looked out for one another,” recalled Owen. “We had to, because we encroached on a normal school where there was a great deal of jealousy.

"In addition, we naturally took all the prettiest girls because we were young footballers playing for England schoolboys. We had one or two serious problems with the local kids and some fights… I remember a big group coming down with baseball bats one day, and us having to run off. There were even attempts to confront us up at Lilleshall.”

Helped education

Teachers, coaches, canteen staff… speak to anybody who worked at Lilleshall at the time and one name always crops up: The Sol Man. “Always polite, could eat for England,” says one cook, who rather sweetly would rather not be named. “He filled the doorframe even then,” says teacher Barry Fisher. “A friend of mine was the maths teacher at the time and he said Sol would always stay behind to do extra maths at lunchtime.”

As the novelty wore off, though, integration became easier, with sport the obvious starting point. “We’d send our football team in groups to train with them at Lilleshall,” recalls Fisher. “Although the Lilleshall boys couldn’t play for our school team – for obvious reasons – they did athletics and played cricket in PE in the summer term. “I remember one lad called Albert who had never thrown a javelin before in his life, so we taught him for 10 minutes on school sports day and he broke the school record with his first throw – 60-odd metres!”

And if a career in professional football was the carrot, school was most definitely the stick. “If they ever stepped out of line educationally they were penalised back up at Lilleshall,” continues Fisher. “They might miss a game, so they had to make sure their schoolwork was up to scratch.”

“I probably did as well, if not better than I would have done at school back in Manchester,” admits Danny Webber, “because we were already in a very regimented environment up at Lilleshall. It was very strange, because you had a bunch of working-class lads effectively going to boarding school, which would never have happened under normal circumstances. Some take to it better than others, but I think as a whole you came out of Lilleshall a better educated person.”

There was, however, the odd reminder that this wasn’t just any old bunch of working-class lads. “Occasionally students would get taken out of school to play in the FA Youth Cup for their clubs,” says Fisher, “and sometimes they’d come back with a win bonus. Most of them would keep it to themselves, but some would say, ‘Ooh, look what I’ve got’, which could cause problems.”

Yet, given some of their former students are now household names, it’s surprising how little evidence there is of their time at Idsall – just a signed Jamie Carragher Liverpool shirt on the wall outside the sports hall, in fact. FFT stops some sixth-form lads to ask whether they know about the school’s historical link with Lilleshall. They shrug and nod vaguely, but struggle to name more than one or two players. Aren’t they surprised Idsall doesn’t make more of it? “Yeah, s’pose…”

Work hard, play hard

Another favourite pastime was sneaking into the gymnastics hall when the gymnasts weren’t there and playing on the equipment

Despite the rigours of school and football, back at Lilleshall’s dorms there was always time for a bit of mischief. “We had some great parties,” recalled Michael Owen of all people, “and usually got caught as we were getting into full flow.”

The most common punishment for stepping out of line, and one that has gone down in Lilleshall folklore, was the dreaded ‘driveway run’. “You think that driveway’s long,” says Webber, “but you don’t realise how long until you’ve had to run down it and back. Usually they made you do it before breakfast but I did mine at 9 o’clock at night in the pitch black.”

At least Webber’s generation had the luxury of games consoles and occasional use of the internet (“although it was dial-up back then, so it took all day”); for early intakes, doing the drive run in the dead of night was considered fun. “We did it to pass the time,” explains Thomas. “As a dare you had to leave handkerchiefs in different places to prove you’d done it.”

Other favourite pastimes included sneaking into the gymnastics hall when the gymnasts weren’t there and playing on the equipment, and ‘battles’ with other rooms. “You were in rooms of three and we used to have battles with Joe Cole’s room, the usual stuff like putting things in people’s beds and practical jokes,” says Webber. FFT even heard rumours – sadly unconfirmed – of a ‘netball knicker club’ involving the stealing of said sportswomen’s undergarments.

End of an era

Howard Wilkinson’s 1997 ‘Charter for Quality’ handed responsibility for developing England’s youngsters to the clubs

There was also a clear hierarchy between the second-year students and the upstarts from year one. “You come in at 14 and you’re all cocky, but the lads who have been there a year see themselves as the seniors,” says Webber. “If you took the mickey out of them or went too far, you’d get called to ‘a meeting’, and it was always in room 208…”

Now, FFT has been to room 208 and there’s nothing particularly scary about it, but you can imagine it would be if you were confronted with three 16-year-old centre-halves coming off the back of a growth spurt. “You’d think, ‘Oh my God!’” says Webber, “but you’d just take a few digs and walk out of there with your head held high.

“We called a few ‘meetings’ the year after, but the year below us were a bit soft, the likes of Leon Britton, Leon Knight and Jermain [Defoe], so we took it easy on them!”

Sadly for many, Defoe’s year would be the last to graduate. Howard Wilkinson’s 1997 ‘Charter for Quality’ handed responsibility for developing England’s youngsters to the clubs, in the form of an academy system based largely on the National School’s model.

Different paths

When I left, I had it in my head that I’d play for the United first team and for England. They were my hopes at 16 and they were probably everybody else’s

But what of the 234 who did pass through Lilleshall’s heavy oak doors? Inevitably, most had stars in their eyes – or, as a mildly amusing ITV documentary on the class of ’95 had it, The World At Their Feet (a typical quote from one player: “To be honest with you, I’m thick”). “When I left, I had it in my head that I’d play for the United first team and for England,” admits Webber. “They were my hopes at 16 and they were probably everybody else’s.”

Webber never did become a first-team regular at Old Trafford, but has still carved out a decent career spent largely in the Championship to date. The striker standing in his way at United has a more cynical view. “They think they’ve made it before they have,” said Andy Cole, who arrived at Lilleshall in 1986. “We had a Vietnamese boat boy in our year and he was at Tottenham. They were saying he was going to be unbelievable. What happened? Nothing.”

Francesco Totti – Rome's greatest son who never got the love he deserved

How important really is the 12th man? Players and experts reveal all...

Indeed, for every future international – and Andy Cole was one of them, albeit after leaving Arsenal and working his way back up the ladder – at least two faded into obscurity. Others, like Rod Thomas, fell somewhere in the middle, making a living in the Football League. But whether they made it or not, every graduate FFT spoke to agrees with Michael Owen that Lilleshall changed them “from a boy to a man”.

Steven Gerrard never actually made it onto the Lilleshall honours board, denied a place at the final trial – as was Frank Lampard. But even he felt the benefits of the National School, using that rejection to spur him on throughout his career. Or, as he puts it: “F*** Lilleshall.”

This feature originally appeared in the March 2013 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!

Join The Club

Join The Club