Class war in Kolkata: Why East Bengal vs Mohun Bagan is more than a game

Football in the world's second most populous nation can attract enormous crowds, particularly when Kolkata's 'big two' are going toe to toe - as Rob Bright found out for the September 2007 issue of FourFourTwo

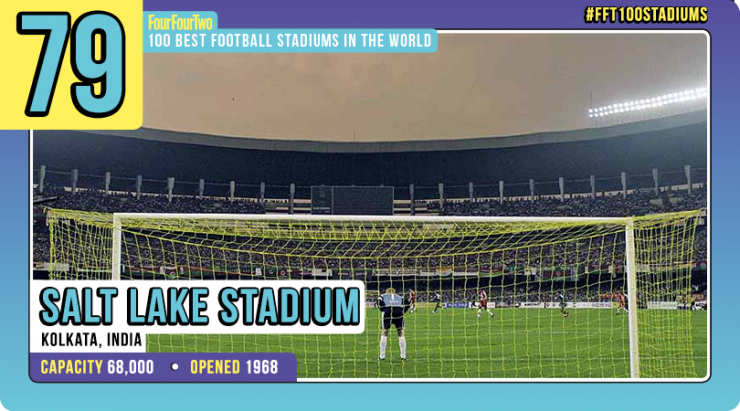

Salt Lake Stadium is a huge, drab slab of concrete that sits, like some wayward Cold War relic, in a northern suburb of Kolkata rather grandly named Salt Lake City. It’s suburbs such as this where that Indian economic miracle you’ve been hearing about is beginning to assert itself, announced in the glittering glass towers and five-star hotels that join the stadium on the skyline like altogether more fashionable and affluent residents.

It’s a couple of hours before kick-off and the crowds are already gathering inside the stadium. Hindi songs crackle from the PA system, the sound of drums rises up through the thick, mosquito-infested air, and fans let off bangers so loud they rattle the spine. The spectrum of colour moves from red and yellow through to maroon and green; the former belonging to East Bengal, the latter to Mohun Bagan, both Kolkatan sides, and the oldest and greatest rivals in Indian football.

If it had been something as significant as a cup semi-final, as it was in 1997, 131,000 would be crammed in here

Given that Salt Lake Stadium can hold about 120,000, their numbers look sparse amid the grey spartan stands, yet over 60,000 are expected here to watch what is an inconsequential league game, Mohun Bagan being well off the pace so far this season. If it had been something as significant as a cup semi-final, as it was in 1997, 131,000 would be crammed in here, and the noise, awesome even now with the stadium half-full, would have been deafening.

Just over 24 hours ago, flying into Kolkata from Delhi, neither I nor FourFourTwo’s photographer, local Bengali Anamit Sen, had managed to secure press accreditation, despite spending weeks wading through the quagmire that is Indian bureaucracy. As the plane began its descent over small tufts of tropical forest, the leaves of palm trees bursting skywards and the late-afternoon sun forming an orange disc on the horizon, reflected in the water of flooded rice fields, I dwelt on the fact that I might not have a story to do once I got here.

Football vs cricket

Comments down the years describe Kolkata as being 'a corpse on which the Indians feed like flies', 'a squalid sump-hole of filth and poverty' and 'a city pursued by nightmares'

For all that, the prospect of being in Kolkata itself was motivation enough for making the trip, and I was buoyed up by this surprisingly idyllic arrival. This is a city, after all, whose grim reputation is hardly the stuff of glossy travel brochures. Comments down the years describe it as being like “a corpse on which the Indians feed like flies”, a place full of “the hot stench of the slow-decaying poor”, “a squalid sump-hole of filth and poverty” and “a city pursued by nightmares”.

Winston Churchill said “I shall be glad to have seen it, namely that it will be unnecessary for me ever to see it again”, while people are ritually warned not to even think about going anywhere near the tap water – “Brush your teeth with cola if you have to,” they are told. It’s not exactly going to have you rushing down to Thomas Cook...

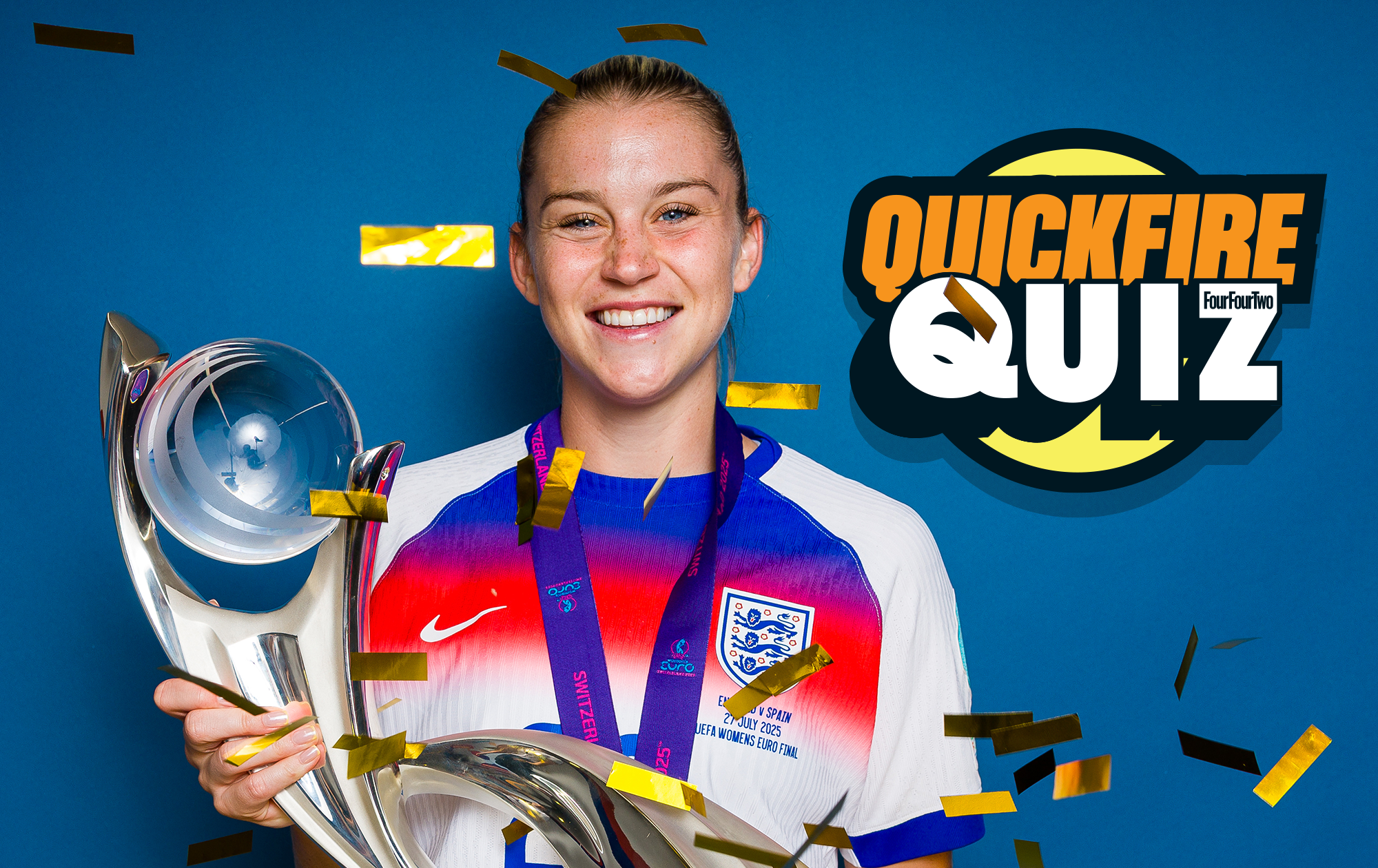

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Yet beneath this wretched first impression, many visitors have discovered, as Anglo-American journalist and author Christopher Hitchens put it, a “fantastically interesting, brave, highly evolved and cultured city which has universities, film schools, theatres, bookshops, literary cafes and very vibrant politics.”

And, as Hitch failed to mention, a fanatical devotion to football. Kolkata was the first city in India to take up the sport, and it remains its emotional heartland, encapsulated by the derby match. When you first hear about this, it comes as something of a shock. Mention “India” in word association and people respond with “curry”, “Taj Mahal”, “Shilpa Shetty”, “cricket”... But football?!

Yet when India gained independence in 1947, most people expected football to become the national sport. It had already been thriving for the previous 50 years, it was cheap to play and it permeated all levels of India’s highly-stratified society, appealing to all classes. It would also have been a more appropriate vehicle to promote the new sense of nationhood, a chance for India to introduce itself to, and compete with, a greater number of countries than the cricket ever could.

And yet, the reasons why it didn’t happen are, in part, the same reasons why Mohun Bagan vs East Bengal still attracts so many fans; football here is still essentially about regional, rather than national pride. This extends to the governing bodies – the game’s history is awash with incidents of in-fighting between states that have prevented a coherent national agenda from ever emerging.

The Indian Football Association, founded in 1892, was the first indigenous institution established for the sport. Its founder, Nagendra Prasad, is regarded as the father of subcontinental football.

It’s to the IFA’s offices that we’re immediately heading. With little time to get things arranged, most Indians would have thrown in the towel by now. The local media normally has to set things in motion months before hand if it wants to get accreditation for a game like this. We have hours.

I’m white and representing the UK press, phenomena that are about as common in Indian football as Thierry Henry warming the subs bench

But we have two advantages: I’m white and representing the UK press, phenomena that are about as common in Indian football as Thierry Henry warming the subs bench. Anamit remains confident that my presence alone will be enough.

After making our way through the pressing heat of the central Kolkata crowds, shirts stuck to our backs, we arrive at the IFA HQ which, despite the illustrious heritage, is a ramshackle collection of poorly-lit rabbit warrens tucked down a backstreet not far from the giant park that dominates the city, known as the Maidan.

We’re here to meet Shri Subrata Dutta, the Honourable Secretary of the IFA, who has yet to arrive, so we’re ushered into an empty office and told to wait. We do, for an hour. Given his status, Dutta can afford to be late. Indians love hierarchy and Dutta’s position makes him a demi-god in this world, a man with enough power to make the wheels turn that bit faster for a chosen few.

Eventually we’re called to another room where Dutta is sitting expansively behind a desk, his bald head shining beneath the fluorescent strip lighting. He apologises for being late and is enormously helpful, promising to make sure we received VIP passes for the game and the necessary IDs in order to take action photographs. “It’s a good job you were here,” says a relieved Anamit.

It’s a neat illustration of how the colonial past still impacts upon the present, often expressed as an exaggerated deference to Westerners. Yet it worked the other way in the past, the game giving the local population the first means by which they could compete with their ‘masters’ on equal terms, a chance to assert their opposition to occupation. “War by other means,” as George Orwell put it.

How football came to India

The British brought the game here with the expansion of trade under the East India company. As the British capital at the time, what was then known as Calcutta was the first city to be exposed to football, games being played as early as 1854, teams made up mainly of the military classes or industrial workers.

Despite the creation of the IFA in 1892, the football league was exclusively for British teams until 1914. Nevertheless, Indian teams were free to play in cup competitions, and it’s here that Mohun Bagan established their reputation as an emblem of national self-esteem, when in 1911 they beat a British side in the final of the IFA Shield, the first native team to do so.

It would fill every Indian with joy and pride to know that rice-eating, malaria-ridden, bare-footed Bengalis have got the better of beef-eating, Herculean, booted John Bull

After the victory, the ecstatic indigenous press reported how “the Bengalees were tearing off their shirts and waving them around their heads”. If that sounds curiously contemporary, another report is even more so, stating “it would fill every Indian with joy and pride to know that rice-eating, malaria-ridden, bare-footed Bengalis have got the better of beef-eating, Herculean, booted John Bull”. It could almost be a blueprint for the notorious Norwegian commentary after their victory over the English in 1981 ‘Margaret Thatcher, Princess Diana, Winston Churchill – your boys took one hell of a beating!’

NEXT: A taste of Brazil in Kolkata

With the bureaucracy finally dealt with, we head out for a taste of Kolkata nightlife. Mother Theresa may have led us all to believe that there was nothing here but misery and deprivation, but walking past brightly-lit modern bars and restaurants in a trendy part of town, it’s easy to see how such a view is offensive to many Bengalis. What depravity there is comes via whispered offers of opium, marijuana and “college girls, full naked”.

I end up in a bar where a band is playing convincing covers of well-known samba tracks. The vibe is loose and easy-going, with everyone just the right side of drunkenness. It’s easy to see how, when the World Cup comes around, Kolkata transforms into a Brazilian outpost, cheering on their adopted side with all the reverence and fanaticism of those in Rio or Sao Paolo.

The love affair with Brazilian football stretches back to 1977, when 100,000 people made a pilgrimage to the Maidan to see Pele juggling a ball. During the 2002 World Cup, crowds gathered on the platforms of the much-celebrated metro system to watch Brazil on the screens there. In the excitement following one goal, a commuter was pushed in the path of a train and died.

A few more mojitos later, the last of the revellers leave the bar, give up the sense of Latin abandon and make their way home, the incessant sound of car horns providing the familiar lullaby.

Come match-day, repeated "No"s down the phone line make it clear that we won’t get access to the players prior to tonight’s game. They will go for the ritual puja (prayer) and then be kept away from the media until after the game. Instead I meet up with Raman Vijayan, a striker for Kolkata’s other major side, Mohammedan Sporting, who made a habit of humiliating British clubs in the 1930s, and have remained a major force.

Life after football

Vijayan is a rangy 33-year-old but looks 10 years younger and played for East Bengal for four years in the mid-‘90s. He explains how important it is for players to get sponsorship from a company who will provide them with a job after they retire. Consequently, clubs are often named after the companies and institutions that finance them, like JCT Mills or Mahindra United.

East Bengal players' average yearly income is around £17,000 – good money in India, but not enough to save for a life outside the game. There are plenty of stories of former greats reduced to selling street food, while some reached a level of destitution that led to suicide

East Bengal players are on an average yearly contract of around £17,000 – good money in India, but not enough to save for a life outside the game. There are plenty of stories of former greats reduced to selling street food, while some reached a level of destitution that led to suicide.

Vijayan didn’t kick a ball until he was 12, when he joined a sports school. He played his first professional game at 20 and was called up to the national side two years later, subsequently earning 18 caps and becoming one of India’s all-time top scorers. So what sort of condition does he think Indian football is in?

“In 1996, when the NFL was introduced, things got better. More sponsors have come into the game, like Vijay Mallaya, owner of Kingfisher beer and Kingfisher airlines, who now sponsors East Bengal. These sorts of people will finance the teams but don’t feel the need to interfere with the coach’s work.”

Unlike some people. Politicians and bureaucrats have used football as a tool to advance their own careers and the game has suffered as a result. What’s more, corruption in India is endemic and football is no exception. A friend in Delhi once told me how he used to get picked for the national youth team over better players because of his influential father.

Indian coaches have so little respect for their own players that they just assume foreigners will be better. Sometimes that’s not the case but they play them anyway because of how much they cost, so their reputation depends on it

Globalisation has led to more familiar problems. “One of the issues at present is the number of foreign players here,” explains Vijayan. “Indian coaches have so little respect for their own players that they just assume foreigners will be better.

"Sometimes that’s not the case but they play them anyway because of how much they cost, so their reputation depends on it. Part of the reason people think like this is from watching foreign games – mainly the Premiership, but also La Liga and Serie A – which are now on TV. Lots of people would rather pay to watch cable than support local teams.”

As Boria Majumdar and Kausik Bandyopadhyay observe in their book on the history of Indian football, Goalless, “Any failure on the part of cable operators to show important European matches has often resulted in their employees being beaten up and their offices ransacked.”

NEXT: How Partition and war exacerbated the rivalry

Partition and rivalry

Such violence surrounding football is not uncommon here, particularly between Mohun Bagan and East Bengal. The rivalry took a more violent turn after Partition in 1947, when refugees flooded into the city from East Bengal. It was exacerbated further in the 1970s when the war for the independence of East Pakistan resulted in the creation of Bangladesh. Once again, refugees from the East poured into Kolkata.

While both sets of supporters are mostly Hindu, sharing a common language and cultural heritage, Mohun Bagan fans regard themselves as more urbane and metropolitan than the ‘bumpkins’ from the East. That has changed as new generations have grown up without the sense of cultural division. These days, it’s not uncommon to find an East Bengal-supporting son to a Mohun Bagan father.

In the 1975 cup final, East Bengal defeated Mohun Bagan 5-0. One fan was in a state of such ecstasy after the fourth goal that he had a heart attack and had to be taken to hospital

Yet there are some remarkable stories of the intensity with which fans treat the encounter. In the 1975 cup final, East Bengal defeated Mohun Bagan 5-0. One fan was in a state of such ecstasy after the fourth goal that he had a heart attack and had to be taken to hospital.

A tragedy all the more bizarre befell 25-year-old Mohun Bagan fan, Umakanto Palodhi, who was so dejected by the defeat that he committed suicide that evening, leaving a note saying, “I wish to take revenge for this defeat in my next birth by returning as a better Mohun Bagan footballer.”

In 1977, after another defeat, one Mohun Bagan fan poisoned himself by devouring a bottle of pesticide, while matters came to a head in 1980 when a stampede killed 16 lives and injured hundreds.

“Do you think there will be violence tonight?” I ask Anamit, as we pogo over the potholed road en route to the stadium. He shakes his head but jokes about getting hold of a helmet just in case. At least it’s mostly a joke... “I remember going to meet my father after a derby when I was a boy,” he says, “and seeing him emerge holding a blood-stained handkerchief to his head. He’d got caught in the crossfire.”

Celebrating a win with fish

Tonight, Mohun Bagan are ravaged by injury, former Bury striker and India captain Baichung Bhutia among the absentees. East Bengal will field their new Brazilian, Edmilson Pardal, who got off to a good start two games ago, scoring twice against JCT Mills. Both coaches are foreign; the experienced Carlos Alberto Pereira da Silva for East Bengal, and the fresher Nigerian, Chima Okorie, who was a big star as a player here in the 1980s.

Dutta’s VIP stamp gives us access to everywhere in the stadium except the changing rooms so we wander around the gloomy interior in search of a bar. But facilities inside prove to be every bit as low-rent as the exterior would suggest and we find nothing. What luxury there is consists of a block of seats sealed off behind lengthy panes of glass, into which cool air is pumped via air-conditioning units to stop Kolkata’s great and good from sweating.

The stiff, austere demeanours of the people taking their seats here are in marked contrast to the fans arriving in the stands, animated faces tribally painted, extravagant hats and banners on display, all manner of instruments tucked under their arms to help generate a suitable din.

Pitchside, India’s press corps are positioning camera tripods, hooking up laptops and smoking with the zeal of relapsed quitters. Bangers increase in frequency and the Bollywood tune reverberating through the PA is increasingly drowned out by the rising chants of opposing fans, the noise creating ghostly echoes in the empty upper tiers. The opposing players emerge onto the pitch and line up for the national anthem and the derby gets under way to an almighty roar.

The principle problems are stamina and strength. After 70 minutes, the players are flagging

Nerves account for some, but not all, of the dodgy first touches and misplaced passes that set the tone in the opening 10 minutes. It’s a scrappy affair, the general level of quality akin to Conference football.

One or two players display moments of skill; there’s some typically Brazilian flair from Edmilson, but like the rest of the outfield players, he lacks any decisive pace, and the whole game runs at about 70% of the speed of your average Premiership match. East Bengal chairman, Swapan Ball, had touched on this earlier in the day: “The principle problems are stamina and strength. After 70 minutes, the players are flagging.”

On 15 minutes we get a goal. East Bengal's Indian striker Saumik Dey breaks free to slot the ball home and is greeted by a wall of noise. More bangers go off, flares are lit and the East Bengal fans erupt in a mass of red and yellow. The drama is maintained by the constant pressure from Mohun Bagan’s enthusiastic youngsters as they search for an equaliser, but they are denied by a few near misses and some outstanding saves from East Bengal keeper Abhra Mondal.

The final whistle goes and the East Bengal fans begin their celebrations. Tonight and tomorrow they will be eating a fish known as Hilsa to mark their success, pushing the prices up in the local markets. Had Mohun Bagan won, prawns would be costing over the odds now. But the Mohun Bagan fans are philosophical about the result, encouraged by the gutsy performances that may help them rise above mid-table this season.

East Bengal goalkeeper Mondal displays an unselfconscious boastfulness, crowing “I am my own hero”

The only violence comes from the scuffles among the press as they jostle for interviews afterwards. When interviewed, Mondal displays an unselfconscious boastfulness that many Indians seem prone to, crowing, “I am my own hero”. Perhaps he was getting carried away in the moment, as happens literally a short time later, when he is held shoulder-high by fans and led out of the stadium with a police guard in tow.

In contrast, East Bengal coach Da Silva strikes a rather forlorn figure, despite victory. As the fifth estate clambers over each other, arms and microphones thrust towards him, he looks like foreigners often do here in India, exasperated and exhausted by the cheerfully irrational and chaotic nature of the culture.

For the football fan, Kolkata is a revelation. If the city’s intellectual life is personified in artists like filmmaker Satyajit Ray and Nobel prize-wining poet Rabrindanath Tagore, football is the barometer of its irrepressible spirit. This is a city that has taken the worst that history has thrown at it and survived, its character not only intact but enhanced. The enduring passion for football captures something of that.

But whether such enthusiasm can be channelled into a successful commercial future is less sure. The dilapidated condition of both teams’ stadiums suggest neglect born of a stifling bureaucracy, not to mention a threadbare budget. But with India’s cricketers returning from the World Cup in the West Indies in shame, maybe people will once again turn to the game that gave them their earliest memories of sporting national pride.

This feature originally appeared in the September 2007 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe!

Join The Club

Join The Club