Long read: It's not the economy, stupid – how football cost Labour a general election

When Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson decided to hold the 1970 general election during the World Cup, he was concerned what effect England's performance could have. Then, four days before the vote, the Three Lions were knocked out...

When Harold Wilson saw Bobby Charlton substituted in the 1970 World Cup quarter-final, the Prime Minister began to suspect the game was up – both for England and for the Labour party’s hopes of re-election in the imminent general election.

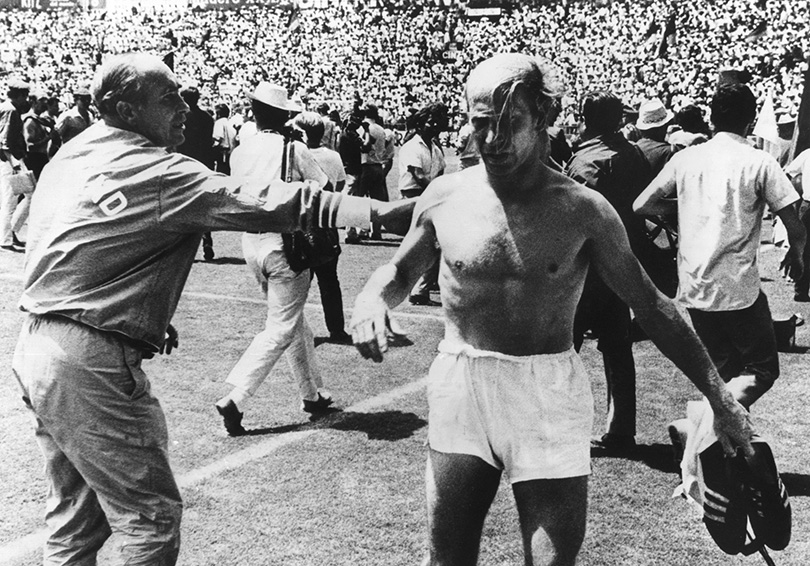

On Sunday June 14, in the merciless midday sun in Leon, England lost a remarkable contest with rivals West Germany 3-2, despite being pre-match favourites and leading 2-0 after 68 minutes through Alan Mullery and Martin Peters. Like many pundits, Wilson felt the turning point had been Sir Alf Ramsey’s first substitution, which came with England leading 2-1.

As he later told Bill Shankly: “I think the mistake was to take [Bobby] Charlton off. That was the signal to the Germans. All they had to do was pile on the attack.”

Four days later, on the morning of polling day, a letter to The Times from Peter Grosvenor presciently enquired: “Sir, thinking of strange reversals of fortune: could it be that Harold Wilson is 2-0 up with 20 minutes to play?”

All but one of the final opinion polls put Labour in the lead, but a swing of 4.7 per cent to the Conservatives ended Wilson’s six-year reign as Prime Minister. Labour lost 76 seats and the Tories, led by Edward Heath, unexpectedly formed the new Government.

Even today, historians and political writers can’t quite explain how Wilson lost.

The announcement of a large trade deficit on the Monday of election week didn’t help Labour’s cause. Wilson was later criticised for staging a comfy, complacent, presidential-style campaign long on personal appearances and short on policy details.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Yet the Labour leader became convinced that England’s defeat had played its part.

In a long conversation with Shankly on a trip to Liverpool in 1975, faithfully recounted in David Peace’s novel Red or Dead, Wilson said: “People get fed up with their government, like supporters get fed up with a team. And that’s what happened. When I heard we [England] lost 3-2, I thought there’d be an effect. And I did hear a lot of voters saying ‘Oh, I can’t stand anything after this.’ It had some effect on the election. Not decisive, of course.”

That seemed to be what he was counting on when his inner cabinet met at Chequers in April 1970 to discuss the timing of the next election. As then-Defence Secretary Denis Healey recounts with unintentional humour in his memoirs The Time Of My Life: “In June, the British football team would be defending its possession of the World Cup in Argentina.”

Not even realising the English were defending the Jules Rimet trophy in Mexico, Healey was predictably unimpressed by Wilson’s fears that “if we were defeated just before polling day the Government would suffer”. Yet Wilson described the World Cup – and the timing of matches – as a “determining factor”. After making a few calls, he was relieved to discover the matches would be played at night.

The ministers at Chequers agreed to wait for the May local election results before deciding whether to plump for June or October. When they showed a swing to the Government, Wilson set the date: June 18, during the climax of the World Cup and, crucially, before many Labour voters in the north were due to go on holiday en masse.

People get fed up with their government, like supporters get fed up with a team. And that’s what happened. When I heard we [England] lost 3-2, I thought there’d be an effect

Wilson was partly gambling his office on his theory of a “mystical symbiosis”, as his Chancellor of the Exchequer Roy Jenkins later put it, between Labour and the England team. This might sound absurd now, but throughout his long political career Wilson showed a keen awareness of the game and its political uses.

In 1966, he tried to persuade the BBC to let him share his expert analysis of the World Cup final with the nation at half-time. In an age when many celebrities had not yet learned to use football to underline their street cred, the Prime Minister’s suggestion was ignored.

When Manchester United won the European Cup in 1968, Wilson mocked his Leader of the House of Commons, Richard Crossman, for his indifference. In his diaries, Crossman noted: “Harold clearly felt this makes me incapable of being a great political leader – because the mark of a leader is to be a man who sees football or at least watches it on television.”

This conviction sprang from Wilson’s own life. He was no football luvvie. In April 1981, appearing on a Granada TV talk show with Shankly as a fellow guest, he was asked by host Shelley Rohde: “I’ve often thought, Sir Harold, your support for Huddersfield is a little out of expediency, or is that totally unfair?” Wilson replied: “Oh no, it’s born loyalties.”

To prove his point, the former Prime Minister revealed that he still carried around with him “the little card from a newspaper called Chums – which I’m sure went out of existence a long time ago – with a picture of the Huddersfield Town team in 1926.” That was the last Terriers side to win the league title.

Wilson then went on to regale Rohde and Shankly, in a stream of reminiscence worthy of Monty Python’s Four Yorkshiremen, how his mother would give him a bob (5p in decimal currency) to go on the tram, get a pork pie or chips and still have sixpence left to buy his ticket, adding: “I had to get there at 10 o’clock because of the crowds.”

He was just 10 years old at the time but the atmosphere of those matchdays made a profound impression on him. On that talk show, which is more famously remembered for Shankly’s remark that football is more important than life and death, Wilson described the game as “a religion, a way of life”.

Six years earlier, Wilson and Shankly had discussed Huddersfield at length, a club the former loved and the latter had managed. Asked by the Scot to pick the greatest player he’d ever seen, Wilson said: “It’s difficult, but Alex Jackson.” Shankly admired Jackson’s self-belief, fondly recalling his habit of going into the dressing room and telling the left-back: “I bet you a new hat I score three goals today.”

It’s a pedant’s point but, as Jackson scored 70 goals in 179 games for the Terriers, he must have been very good at sensing when he was likely to find the net. Some left-wing intellectuals have shared a habit of distrusting football’s mesmeric hold on the masses, regarding it – like religion before it – as another opium for the working classes.

Yet Wilson didn’t just love the game; he relied on it as a politician. His attachment to Huddersfield Town, along with his trusty pipe and raincoat, helped to position him as a man of the people. The contrast proved especially effective when he was vying for votes against yacht-sailing, organ-playing Heath. He used the language of football to communicate with colleagues, the media and the public.

In 1964, when he became the first Labour Prime Minister in 13 years, he was the only member of his government who had previously served in a cabinet. He later explained his role as follows: “I’d take the penalties; I acted as goalkeeper; I went and took the corner-kicks; I dashed down the wing.”

In short, he had to do everything because nobody else had any experience. Changing the analogy, he picked up on a Liverpool Post story that likened him to a football manager, and said: “And where does a manager sit? On the substitutes’ bench! I was reminding my team that I’ve got people on the bench at least as good as anyone who is on the field.”

Wilson's attachment to Huddersfield Town, along with his trusty pipe and raincoat, helped to position him as a man of the people

When the sting of defeat in 1970 had eased, Wilson would refer to the result as a “relegation”. In the February 1974 election, when Heath ended up with four fewer seats than Labour but tried to form a coalition with the Liberals, Wilson remarked: “It’s as if the referee had blown the whistle and one side had refused to leave the field.”

Back in 10 Downing Street after coalition talks failed, and able to form one of the most experienced cabinets since the Second World War, Wilson decided his role had changed. “I’m going to be what they used to call a deep-lying centre-half. I can’t say I’d be a sweeper, because no one outside football would understand.”

Some of Wilson’s rhetoric irritated his colleagues. For every Tony Crosland, the Education Secretary who invariably slunk off with the government chauffeurs to watch Match of the Day, there was a Tony Benn, a full-throated socialist who, while aware of potential political complications, never had much time for the game.

Yet in the 1960s, with Wilson marketing himself as the British JFK, promising to modernise Britain through the “white heat” of science and technology, the upturn in fortunes of the England team – and English football – was a feelgood factor Labour were never likely to ignore. Wilson certainly eked every last advantage out of England’s World Cup glory.

I’m going to be what they used to call a deep-lying centre-half. I can’t say I’d be a sweeper, because no one outside football would understand

He had thrashed the Tories – and Heath – in the March 1966 election, racking up a 96-seat majority. By July the gloss had come off that triumph, with cuts in spending and tax increases outlined in an emergency budget designed to avert an economic crisis. Faced with such troubles, the Government did all it could to bask in England’s glory, with Wilson – at Wembley for the final – milking the applause at the celebration banquet.

After the final, a finger-wagging FA newsletter, written in the admonitory tone of a public-school headmaster, suggested that the entire nation could learn from Sir Alf Ramsey’s heroes: “[The victory] is indeed one of the few bright spots in the sombre economic situation which faces the country this summer. We feel sure that many of our export industries will derive… a welcome boost from this success. The players who have made it possible worked hard and made many sacrifices. They have set an example of devotion and loyalty to the country which many others would do well to follow.”

Coming into office with the promise of a scientific revolution that would transform the country, Wilson must have relished a Daily Telegraph story that praised Ramsey’s “almost scientific assault on the trophy”. Putting his failure as a wannabe football pundit behind him, he asked the electorate: “Have you ever noticed how we only win the World Cup under a Labour government?”

The question irked Heath, who noted in his memoirs that he had been rather more circumspect about Arsenal’s first domestic Double in 1971: “Unlike Harold Wilson five years earlier… I saw no justification for claiming the credit.”

Labour were convinced that the spoils from England’s World Cup win would come to them. In his diaries, Crossman said: “I must record a big change in Harold’s personal position. It has been a tremendous help for him that we won the World Cup.”

Crossman was so euphoric that he told his wife “the World Cup could be a decisive factor in strengthening sterling… Our men showed real guts and the bankers, I suspect, will be influenced by this.”

Putting his failure as a wannabe football pundit behind him, he asked the electorate: 'Have you ever noticed how we only win the World Cup under a Labour government?'

Alas, the guts displayed by England’s footballers failed to sway the bankers, and within a year the Government had to do something it had promised it never would: devalue sterling. The news that the currency was suddenly worth 14 per cent less against the dollar was such a jolt that Wilson felt obliged to assure the nation that “the pound in your pocket” hadn’t lost its value at home.

By 1970, with the economy stabilising, Wilson more popular with voters than Heath and millions of consumers savouring the difference that owning cars, TVs, washing machines and refrigerators had made to their lives, the Tory lead in the opinion polls had shrunk. Yet as the election campaign started, with a poll giving Labour a 7.5-point lead over the opposition, the Prime Minister never forgot about the World Cup.

At the end of May, when England captain Bobby Moore was arrested in Bogota for allegedly stealing a bracelet, Wilson was quick to intervene with the Colombian government. Moore was freed on May 28, 1970 on the grounds that there was insufficient evidence against him. The day after the England captain’s release, the Queen officially dissolved Parliament, with the general election set to follow three weeks later.

The nation might have been relieved that Moore could finally join an England squad due to face Romania on June 2, but Foreign Office officials, suddenly inundated with pleas from jailed Britons across the world, were not so chuffed. One civil servant complained snootily that “the Prime Minister took action on Moore’s behalf for political reasons during a general election campaign and I see no reason why we should allow this somewhat dubious intervention to colour our attitude in future.”

After a 1-0 victory over Romania, England came agonisingly close to earning a draw against Brazil on June 7. Their 1-0 loss in Guadalajara prompted Benn, then Minister of Technology, to note in his diary: “Today, Brazil beat England in the World Cup: the political effect of this can’t be altogether ignored.”

Following a 1-0 win over Czechoslovakia on June 11, a runners-up spot in Group C earned Ramsey’s defending champions a trip to Leon to face West Germany in what would prove to be one of the most controversial games in England’s World Cup history.

There are more explanations for England’s loss in Leon than there are for Wilson’s defeat in the 1970 election. Some see conspiracy in Gordon Banks’ dodgy bottle of beer (the great goalkeeper missed the game with an illness). Others castigate Ramsey for his tactics, arguing that 4-4-2 was never going to succeed in the Mexican heat. A few pinned the entire catastrophe on Banks’s replacement, Peter Bonetti.

Although Wilson felt Ramsey had made the wrong substitutions, he still rang the manager to commiserate and congratulate him on a “magnificent performance”.

Upon hearing the news on the campaign trail, Roy Jenkins remembered the “mystical symbiosis” between Labour and the England team, and wondered how this defeat would play out on polling day. Benn was quick to muse: “Tonight England was finally knocked out of the World Cup which, no doubt, will have another subtle effect on the public.”

The effect might have been mystical but it wasn’t subtle. The morning after the match, Jenkins and Minister for Sport Denis Howell had a meeting in Birmingham. “Roy was totally bemused that no question concerned either trade figures or immigration, but solely the football and whether Ramsey or Bonetti was the major culprit,” Howell recalled. “I tried to be good-humoured about my answers, but for the first time I had real doubts and knew the mood was changing fast – and afterwards my wife Brenda came back from canvassing and said, ‘I don’t like the smell of it all; it’s just like 1959 all over again.’”

In October 1959, the British electorate, largely agreeing with Prime Minister Harold Macmillan that they had “never had it so good”, gave the Conservative Government a 100-seat majority over Labour. The 1970 election wouldn’t be that one-sided, but Heath went into office with a healthy majority of 30.

Tonight England was finally knocked out of the World Cup which, no doubt, will have another subtle effect on the public

So how much difference did that World Cup quarter-final defeat make? Elections are, by and large, a referendum on how people feel about themselves and their country. If voters feel, as Macmillan suggested, that they’ve never had it so good, it might take a scandal of Watergate magnitude to convince them to choose a new government. If they are unsure or fear that things are likely to take a turn for the worse, they are more likely to vote for change.

A nation’s sense of wellbeing is influenced by a multitude of factors. Within 24 hours of England’s loss at the hands of Beckenbauer and friends, the headlines were dominated by a hefty balance-of-payments economic deficit. These two unexpected hammer blows seemed to reinforce Heath’s warnings that things were not as the Government was insisting, and that without change things would only get worse.

The nature of that quarter-final defeat – and the identity of the victors – also seemed to fit a particular political narrative. Here was a country that in 1966, full of optimism about modernisation, could conquer the world, but by 1970 had declined. This narrative echoed what Heath had been saying since the start of the campaign, rather than Labour’s message, which was encapsulated in the buoyant title of the party’s election manifesto: ‘Now Britain’s strong – let’s make it great to live in’.

So it is entirely probable that some voters, still traumatised by images of Gerd Muller slamming the ball past Bonetti to score West Germany’s third, concluded that Britain was not as strong as Labour insisted and voted Conservative.

As a rule of thumb, higher voter turnouts tend to favour Labour and in 1970 only 72 per cent of the electorate voted, down from 76 per cent in 1966, so it’s possible many Labour supporters simply stayed at home.

Crosland certainly felt he knew who was responsible for Labour’s “relegation”, putting it all down to the “disgruntled Match of the Day millions”. And if he was right, a government that took office in 1964, promising to revolutionise British society through the “white heat” of technology, came undone nearly six years later on a football pitch in the white heat of Leon.

This feature first appeared in the June 2015 issue of FourFourTwo magazine. Subscribe for only £9.50 every quarter – that's just £2.90 per issue!

NOW READ...

LIST Ansu Fati becomes youngest Champions League goalscorer – but what happened to the others?

QUIZ Can you name the 50 best teams ever in the European Cup/Champions League?

GUIDE Premier League live stream best VPN: how to watch every game from anywhere in the world

Join The Club

Join The Club