When Nottingham Forest ruled Europe: The story of Brian Clough's continental conquerors

With continental competition set to return to the City Ground this term, FFT relives the story of how Old Big ’Ead captured Old Big Ears and then retained it the following season

Things were moving somewhat slowly in Nottingham, as 1974 dissolved into 1975. Not just outside, where pit smoke still spiked the air, but inside the Palais nightclub.

A 1920s revolving dancefloor moved the various perms, flares and star-jumpers past your table at a rather stately pace as the disc jockey played the maudlin, chugging Billy, Don’t Be A Hero by local group Paper Lace.

At the bar, a group of lads passed a petition around. It was handed to a 19-year-old carpet-fitter from Long Eaton, who read ‘We, the undersigned, ask Nottingham Forest Football Club to appoint Brian Clough as manager’, and looked down through the hundreds of signatures, before adding his own. The petition was soon presented at the City Ground. Things were about to start moving a lot faster.

Several decades on, as he spoke to FFT, that carpet-fitter pondered the hurricane that was about to descend on an unsuspecting city. “It was ridiculous,” Garry Birtles said. “Ridiculous but great. Ridiculously great.”

The hurricane’s name was Brian Howard Clough. It made landfall at the City Ground on January 6, 1975, unable to do much damage to a place already in ruins.

13th in Division Two, Forest’s Christmas present to their fans had been a 2-0 home defeat to local rivals Notts County. Promising striker Tony Woodcock was about to be sold on to Lincoln City. Disenchanted midfielders Martin O’Neill and John Robertson were on the transfer list.

“The players could do well one week, but they couldn’t keep it up,” said manager Allan Brown. “It was like something inbred in the club.”

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

A ramshackle edifice of tin and wood, the City Ground had just one modern stand, and that was only because its predecessor had burned down in 1968.

“It was a club that had absolutely nothing,” said Duncan Hamilton, author of the award-winning Clough memoir Provided You Don’t Kiss Me. Within five years, Forest would be a club with everything, and all thanks to a manager that no-one else had wanted.

Grasping the nettle

Despite his 1972 title win with Derby, Brian Clough was damaged goods by January 1975. At the Baseball Ground, he’d fallen out with the directors. At Leeds, he’d fallen out with the players. In between, he’d gone to Brighton and fallen out with the town itself, which stubbornly refused to move closer to his Derbyshire home.

Even when desperate Forest called, it was on their terms. A pay cut from his Leeds days, no big money to spend on transfers. There was a slice of luck in his first game. Forest pulled off an FA Cup shock, but only after Spurs were caught in traffic and arrived just 10 minutes before kick-off. “I would warn our supporters that this is not the start of anything special,” said the new manager, and in the short term, his assessment was correct.

Forest went three months without a win and, as Clough laid into his players, he was starting to look like a busted flush. A raid on Leeds for a player he’d taken to Elland Road looked like the work of a desperate man. Even before Clough’s 44 days were up, John McGovern had attracted the derision of Leeds fans, a fully-fledged terrace hate figure at the club.

The following season brought only four wins in Forest’s first 16 games, but a strong finish, which pushed the club to eighth, at last provided momentum. The real work was done in the close season. Back page stories, encouraged by Clough, linked the ever abrasive northerner to genteel Highbury.

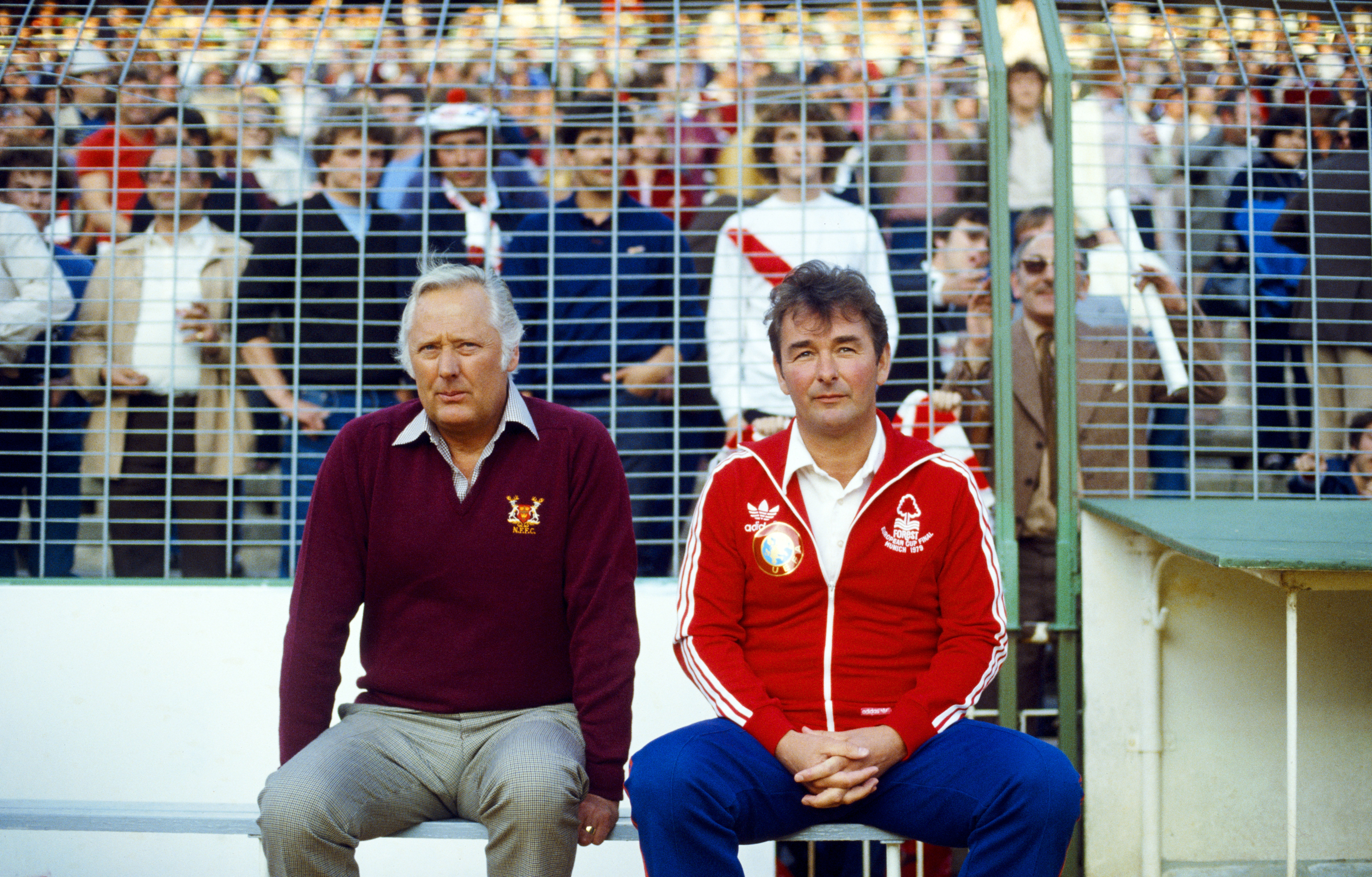

Forest blinked and the first battle of a war of attrition with the club’s ever more powerless suits was won when Clough got the go-ahead to bring in Peter Taylor, his former Middlesbrough team-mate and Derby assistant, back from Brighton, where he’d succeeded the Leeds-bound Clough.

Taylor’s arrival, and the way it was orchestrated, set a pattern for years of magnificent mayhem. Clough lived in the headlines, linked constantly with jobs at Manchester United, at Derby, at Villa, Sunderland, in Dubai and the USA, and even the Welsh national team. His sideman worked under cover, disguising himself in a bobble hat and glasses to scout the players who formed Forest’s great side. Working together, said writer Hamilton, “they were two people of one mind.”

Birtles saw closely how they worked in tandem. “Peter would have a sixth sense of how you were feeling,” said the forward, signed from non-league Long Eaton United in 1976. “Brian would take on what he said and reach into your psychological DNA to find the way to motivate you.” But even as the basis of a great side – the guts of veterans Larry Lloyd and Frank Clark, the guile of Robertson and O’Neill, the goals of Woodcock – was assembled, promotion was far from a certainty.

On May 14, 1977, with Forest’s league fixtures complete and Bolton needing a win and a draw from their final two games, Clough had written off his team’s chances and skulked off to Mallorca, telling the press: “I have arranged for the place to get the Bolton result and I shall be having a glass of champagne at 3pm, and another at 5pm, no matter what happens.”

In the end, more than a glass was needed as Bolton fell short at the first hurdle, losing at home to Wolves. Forest went up with 52 points, the fifth-lowest haul of any promoted side in history, having lost 11 of their 42 games.

Even then, consolidation was not a word in Clough’s vocabulary. “I’m not looking to just stay up with the Liverpools, Man Uniteds and Arsenals,” he told reporters at the start of the season. “I’m going up to piss all over them. The lot of them.”

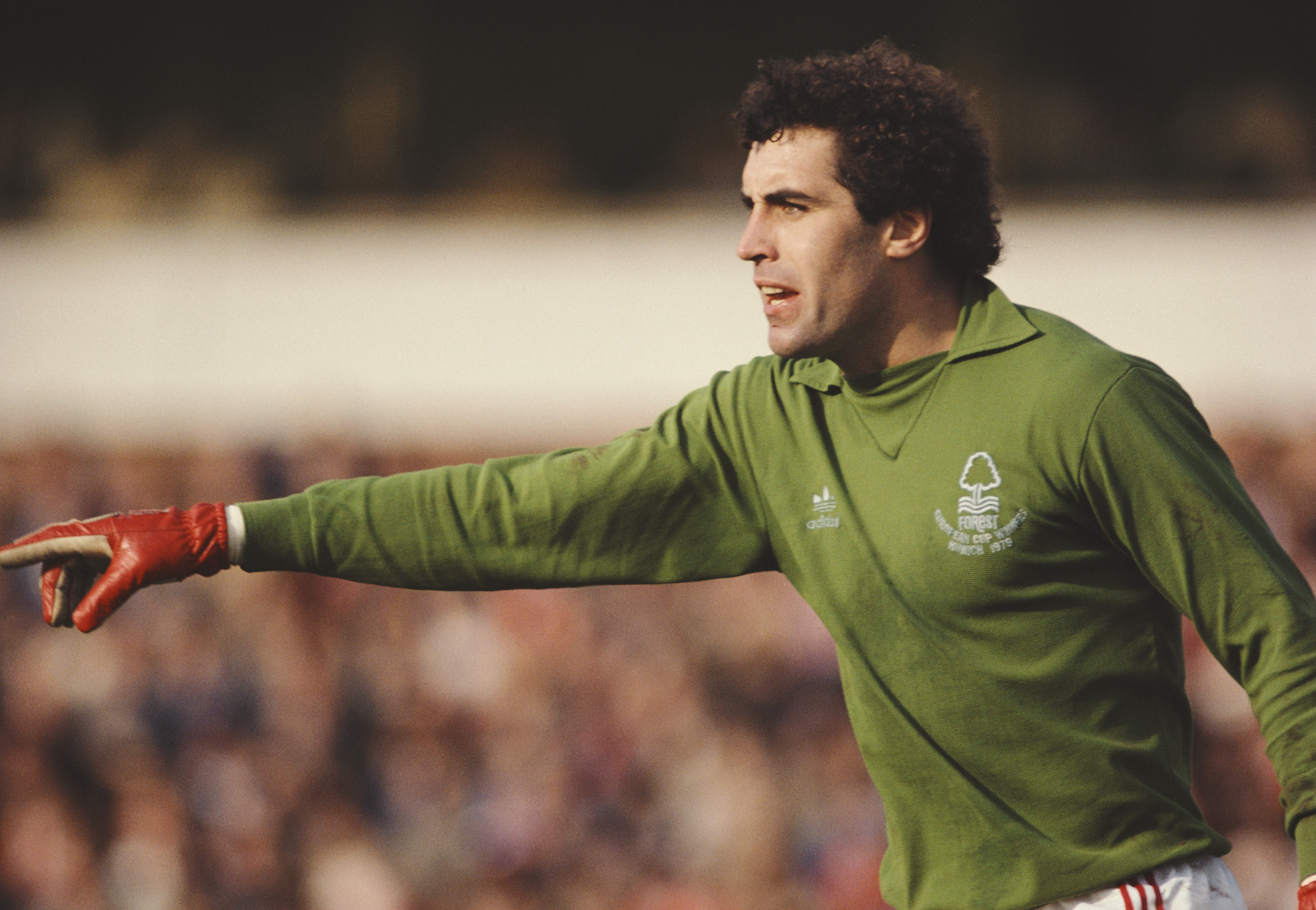

After a mauling at Highbury, Clough did just that, with the aid of two key signings. Peter Shilton was rescued from relegated Stoke for £270,000, a world record fee for a goalkeeper. Taylor also persuaded Clough to buy Birmingham’s striker Kenny Burns, who Clough had derided as “an ugly sod, a thug and a sh*thouse”. On arrival, Burns was converted into a central defender, having first satisfied Clough of his malleability by meekly accompanying the manager to a flower show.

In those days, before Clough’s eccentricity caricatured him, he was characterised by it. Expensive signings would be ordered to retrieve balls from nettle patches. Poor performances resulted in rambles down the banks of the Trent for catering van soup. Team talks could consist of the squad staring at a football for five minutes while Clough soliloquised.

At short notice, the team might be sequestered in hotels in Scarborough, Derby or Clough’s favourite Spanish hideaway, Cala Millor in Mallorca.

Bonding through alcohol was often encouraged, the squad establishing post-training headquarters at Uriah Heap’s wine bar (where an 11.50am kick-off was regarded as tardy) and undertaking post-match analysis at Madison’s nightclub. “There was no sense that what we did was strange,” Birtles said. “It was only when we all moved away that you discovered other clubs didn’t do things like that.”

‘Sweden is boring’

Away from the madness, Forest on the pitch were a thrilling proposition.

A flexible 4-3-3 allowed Robertson to push deep on the left and curl crosses towards Woodcock and Peter Withe. In midfield, Archie Gemmill roamed from the left and O’Neill drifted in from the right, with McGovern a ball-winner and passer. Behind them, the view was uncompromising: Clark on the left, Lloyd and Burns in the centre, Viv Anderson on the right. That irresistible mix of pragmatism and technique was easily the equal of the giants of Anfield. By October, promoted Forest were top of the league and their manager was assuring writers that despite their status as defending league and European champions, “Liverpool aren’t the best team in the country, ’cos we are”.

Arsenal goalkeeper turned BBC pundit Bob Wilson assured Football Focus viewers that “the Forest bubble will burst”, while one newspaper referred to them as “caretaker leaders”. Then, in December 1977, Clough was invited to Lancaster Gate to interview for the England manager’s job.

It was an extraordinary three hours, deep inside the FA’s old headquarters. Manchester City’s chairman Peter Swales remembered it as a stitch-up orchestrated by FA chairman Sir Harold Thompson, with the intention of giving caretaker manager Ron Greenwood the job. Others say Clough was thoughtful, confident, inspirational.

What’s not in doubt is that Clough demanded the team’s colourful new Admiral strip be scrapped as a condition of taking the job and accused the FA’s secretary Ted Croker of talking “bullsh*t” about the need to focus on commercial matters. “I felt it went well,” Clough said, cheerfully. Of course, he didn’t get the job he wanted, but his side were able to take out his frustrations on opponents. Manchester United were beaten 4-0 at Old Trafford, remembered by Shilton as “the first time we really believed we could win the title”.

Robertson’s penalty won the League Cup against Liverpool. The manager took home his spoils, setting the trophy down on top of his television for his children to admire. Finally, with Forest on what would become a 42-game unbeaten run, they clinched their first title with four matches to spare. Clough celebrated by letting it be known that he and Taylor might leave for Sunderland.

In truth, the pair were going nowhere. Clough had already assumed full control at the City Ground. Only he could give the go-ahead to ground developments, renegotiate contracts and conduct transfer business. No wall at the ground could be painted without his sanction. Forest stumbled early on in the new season, going four games without a goal and Clough blaming diffidence brought on by their success.

“Being champions has turned us into a team of non-talkers,” he said. They then drew holders Liverpool in the first round of the European Cup. Given no chance, the emerging Birtles helped to establish a 2-0 home lead, before the European champions blew themselves out on the rocks of Shilton’s resistance at Anfield.

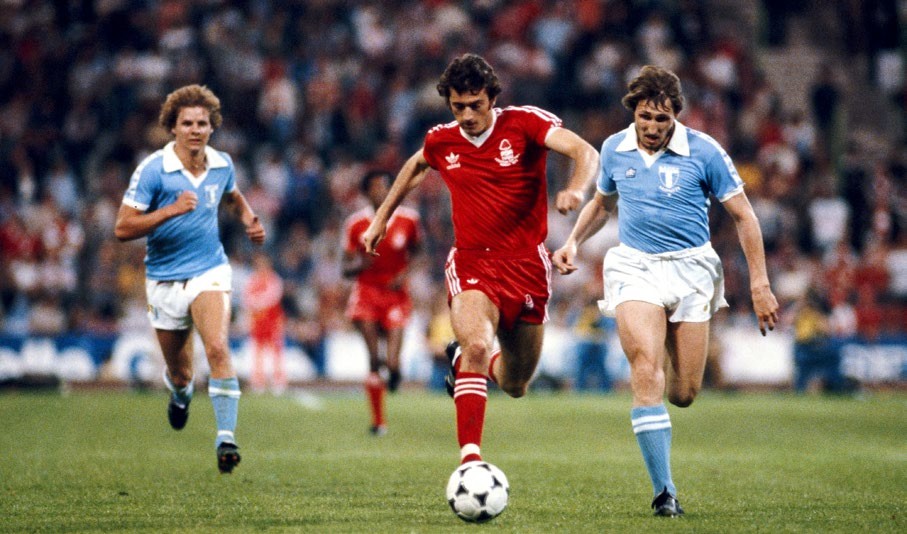

The rest of that campaign was largely conducted in swashbuckling style, with a 7-2 aggregate victory over AEK Athens followed by a 5-2 win over Grasshoppers of Zurich and a 3-3 home draw against German champions FC Köln in the first leg of the semi. Ian Bowyer’s goal in Cologne put Forest through to the final and what seemed a formality against Swedish side Malmo.

Who's Kevin Keegan?

Forest slipped further behind during the following season, finishing 12 points back in fifth, as Aston Villa claimed the title. Having beaten Barcelona to win the Super Cup, Forest progressed past Swedish club Oster, Romanians Arges Pitesti, East Germany’s Dynamo Berlin and the mighty Ajax in the European Cup, providing the opportunity to retain their status as continental kings in the final against Kevin Keegan’s Hamburg.

Clough did his best to play down the significance of having to face England’s talismanic forward in Real Madrid’s Bernabeu. In any case, setting up to counteract a specific team, let alone a player, was forbidden under the Forest ethos. In the week before the final, Clough sent his men to Cala Millor with no training scheduled, no curfews and no alcohol restrictions in place. This time, it nearly went wrong.

Hamburg bossed matters for much of the final. The exception came in the 20th minute, when Robertson cut inside the otherwise immaculate Manfred Kaltz, edged to the D and finished with a low drive. Not for the last time, an English team had been outplayed by German opposition in a European Cup final and still took the trophy home.

“At half-time, I wondered how we could last,” admitted Clough. “We could have taken three off. When Birtles came off at the end, he didn’t even have the strength to remove his own shinpads.” Forest returned to England as heroes, albeit ones in need of minor tinkering. Yet there was a sour smell in the air, put there by Clough’s short-lived attempt to strip O’Neill of the captaincy, and there followed a close season as disastrous as 1976’s had been fruitful.

Within weeks, Burns, Birtles, Clark, Francis and Lloyd were all gone as Clough planned his second great team. But Taylor was unable to continue his success with transfers. The strategy, Clough later conceded, “was barmy, we were worried that some players might age too quickly – we’d never worried about that before, only about talent”.

By the start of the following season, the managerial team were barely on speaking terms, the result of Taylor’s decision to pen the first autobiography in which the subject was a supporting character. Clough claimed no advance knowledge of the book, and even though the title With Clough, By Taylor made the hierarchy clear, he viewed it as treachery. Sidemen Ronnie Fenton and Liam O’Kane quickly became the manager’s confidantes, with Taylor referred to only as “him down the corridor”.

Forest drifted. Defeated by Valencia in the Super Cup, then knocked out in the first round of the European Cup by CSKA Sofia, they were seventh in the league in 1980/81, and almost lost Clough to heart trouble over Christmas. In his absence, Taylor had the chance to emerge from the shadows. Yet the pressure to succeed with the string of poor signings, including misfiring strikers Justin Fashanu and Peter Ward, saw him suffer a kind of breakdown, left rooting through his own office for bugs planted by his best friend.

By the end of the next campaign, in which Forest finished a miserable 12th, Taylor was gone. When he returned 186 days later as manager of Derby, Clough was rather unamused. After Taylor took advantage of a Clough family holiday to sign Robertson in 1983, Clough was livid. The two never spoke again.

“We pass each other on the A52 going to work on most days of the week,” said Clough. “But if his car broke down and I saw him thumbing a lift, I wouldn’t pick him up. I’d run him over.”

In light of what happened to Clough and the club after the peak, it’s very tempting to write off everything after 1980 as failure. It wasn’t. In 1984, they finished third and might have won the UEFA Cup, having overcome Celtic in the

third round, but for semi-final foes Anderlecht bribing the referee. Forest returned regularly to Wembley, playing arguably more stylish football than ever. After Taylor’s sudden death in 1990, the decline began in earnest. Badly shaken, Clough relied on his twin weapons of bravado and alcohol until even they failed him. He still might have gone gracefully but for Forest’s financial problems, which forced him to start his final season with Teddy Sheringham and end it with Robert Rosario.

After a sad, inevitable relegation in 1993, there was nothing left to do but write the autobiography. “To Peter,” the dedication read. “You once said ‘When you get shot of me, there won’t be as much laughter in your life’. You were right.” Yet the force of nature that was Clough deserves a better epitaph.

Senator George McGovern’s response to the suicide of his friend Hunter S Thompson is more fitting. Asked about whether Thompson had wasted his talent after the 1970s success of Fear & Loathing In Las Vegas and Fear & Loathing On The Campaign Trail, the politician replied, “You know, you don’t have to write more than two masterpieces.” From August 1977 to May 1980, Brian Clough wrote three.

This article originally appeared in the April 2008 edition of FourFourTwo

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Join The Club

Join The Club