Cesc Fabregas: Q&A

"If I get something wrong, if I play badly, if I fail, I like people to have a go at me for it"

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

FourFourTwo Daily

Fantastic football content straight to your inbox! From the latest transfer news, quizzes, videos, features and interviews with the biggest names in the game, plus lots more.

Once a week

...And it’s LIVE!

Sign up to our FREE live football newsletter, tracking all of the biggest games available to watch on the device of your choice. Never miss a kick-off!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

London: A whitewashed studio down a quiet, anonymous back street off the Holloway Road. It is the morning after the night before – the night Arsenal crashed out of the Champions League, effectively ending their season with three months still to run.

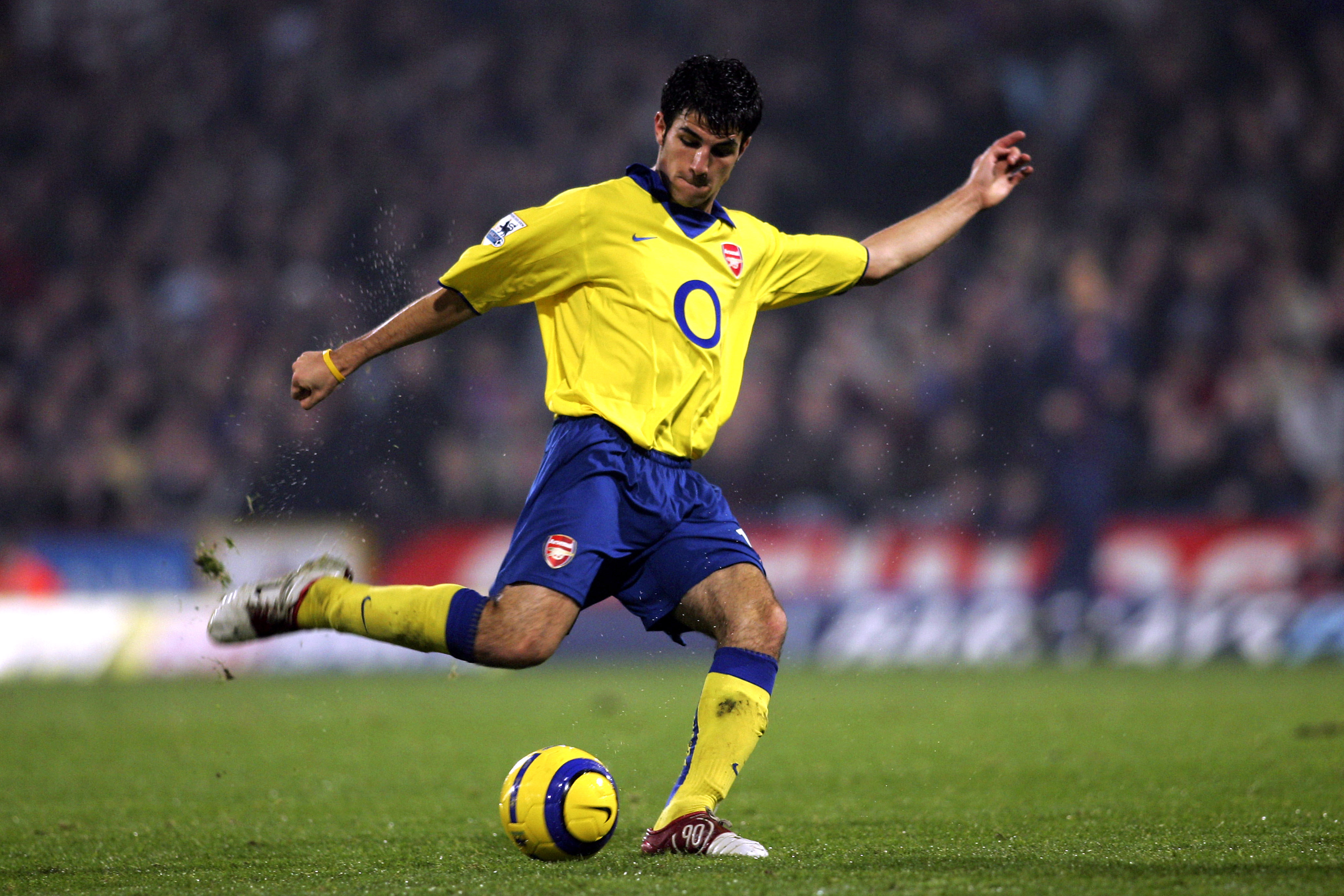

While Arsenal have occasionally glided with silky smoothness only to stumble when it really mattered and ultimately come up short, the man that FourFourTwo has come to meet has been an unqualified success. We’re here to crown Francesc Fabregas our Man of the Year.

Some fans rate Cesc as the finest passer that has ever graced the Arsenal midfield. At the heart of everything Arsenal produce, always demanding the ball and using it with vision and efficiency, he has shown remarkable consistency since joining from FC Barcelona's B team three years ago – which is more than can be said for many of his team-mates.

Not for him the blistering start, subsequent collapse and slow fizzle of the new arrival; the man from the Catalan town of Arenys del Mar, famous more for its turnip festival than its footballers, has been on a constantly upward trajectory since touching down in London.

But with Cesc, it is the character rather than the class that is striking, the manner in which he has taken on Patrick Vieira's shirt and his mantle – even going so far as to utterly outplay the former Highbury favourite when Arsenal faced Juventus in last season’s Champions League.

It was a powerful, compelling statement of intent. Already an obvious candidate for the Arsenal captaincy, Cesc has demonstrated rare confidence, desire and leadership, maturity, personality and intelligence, allied to a sense of responsibility and a fighting quality that so delights fans. And he's still only 19.

For a fleeting moment he almost looks it, too, as he strolls into the studio with a paper plate in one hand, cake in the other, crumbs tumbling down his chest. It is, he smiles, the only chance he's had to eat anything all day.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

He is running late and while it is not his fault, we have a problem: Cesc should already have left half an hour ago. He poses for photos but there's no time for our interview, so we arrange to meet in Madrid and Cesc makes a dash for it. But where is he going? He pauses as he races out the door: "French lesson".

Madrid: The Spanish Football Federation's training headquarters. Cesc pulls up a chair in an empty medical room, anatomy charts on the wall, stethoscope looped over a hook. He's not your average footballer, and certainly not your average 19-year-old.

There is none of the self-obsession or the awkwardness, none of the surliness or bland platitudes. Instead, he is articulate, likeable and engaging. And as he ponders what went wrong for Arsenal and what went right for him this year, Cesc displays the intelligence, insight and determination that has made him such a favourite at Arsenal.

When we met in London, you had to rush off for a French class. Some would say that's a telling commentary on Arsenal!

No, no, that's not why [breaks into a grin]. These days you have to keep studying, not least because my mum tells me so. It's logical: in a few years time I'll speak the three most important languages in the world – English, French and Spanish.

You certainly seem to have mastered English already

Although I studied it at school, I hardly spoke any when I came. But after three years in London it's normal to be able to speak English. If you go to a country you have to go with the desire to learn, adapt, and really integrate yourself. Coming to England wasn't a chore, it was an opportunity. If you speak English you can go anywhere in the world and the chance to learn the language whilst playing �football was really attractive.

When FFT came to London, it was the day after Arsenal had been knocked out of the Champions League, and yet we were interviewing you as Man of the Year. How do you judge a year when you have been superb, but the team has ended up disappointed?

Personally, I've felt physically good, avoided injury, and I've played well. But you can't do anything on your own and my performances are down to the team. We played well this year: until a while ago we were in every competition but now we're in none, which leaves you disappointed. On a personal level I'm happy, but as football is about what the team achieved I can't be satisfied. If the team hasn't achieved everything it could have achieved, that means I should have done more.

What did Arsenal lack?

The ability to finish off the job; we need to make our football pay off and put away our chances. Above all, we need more experience and more intelligence in the final minutes. We've blown a lot of games in the dying minutes – although it's true that we've won a lot late on, too – and our concentration needs to improve. Sometimes we think that at 1-0 or 0-0 in the last minute it's all over. It's not.

Are Arsenal overconfident?

I wouldn’t say it's a problem of overconfidence so much as one of concentration. We can't be cocky – how can we be cocky when we're 17 points off Manchester United? That would be bad, very, very bad. I know my team-mates and I don't think that it's that. We're confident because we believe that we have a good team but we have to work a harder. Sometimes, it's as if [Cesc turns to English] we switch off [back to Spanish], you know? I don’t know why … [a deep, confused frown comes across his face].

You almost look like you have a headache trying to work out why things go wrong, as if you can't fathom it.

It's hard. You watch your team play well, you enjoy the matches, you seem to be playing great football and creating chances but then the results don't follow and you start to wonder: “What's going on? If we're playing well, why aren’t we winning?” You have to really go for the victory because if you have an attitude of “Ah, no worries,” well, then … [Cesc's words trail off] I sometimes get the feeling after games that there's a sense of: “no pasa nada” [no problem]. And that can't be; we can't allow that. We're a great team and we're obliged to win. What I want, and what I think everyone else wants, is to win. At the end of every game, people have to analyse what happened and improve for the next game. If not, we won't progress.

That sounds like Arsenal are too relaxed. Do you lack edge, desire or pride?

I'm not saying that we lack that, not at all. Arsenal are a winning team. But what I am saying is that there are times when we could do more. There are moments when people say: “well, we lost that match but we'll win the next one”, or whatever. No, no, no. Every player has to look at himself and try to be better in the next match, to make sure that what happened was just one bad day.

The image emerging is of a dressing room that accepts defeat …

If I get something wrong, if I play badly, if I fail, I like people to have a go at me for it. If I get it wrong, I want someone to tell me I have got it wrong, to make that clear to me.

Does no-one do that?

Yes. But amongst ourselves sometimes there's a kind of fear of saying things to each other. Maybe we have to lose that fear. If I fail, I want you to come up to me and tell me so, I want you to scream at me, have a go at me. That way I'll be ready next time; forewarned.

Are Arsenal too nice?

Well … [long pause] … Because critics certainly say so. There's a feeling that Arsenal play very nice football but that they lack balls. I wouldn’t say we lack balls, but I do think that we have to … [pause] … I watch Chelsea and United and I see them go for every ball, give everything in every match. And that comes from unity and desire. Sometimes I run for you, sometimes you run for me – that's solidarity. You need that to achieve great things.

After the Carling Cup final all the plaudits were for Arsenal, but Chelsea were the team who won the trophy. Do you feel like the bad guys always win?

Yes, yes, definitely. I'd prefer them to get all the plaudits while I walk away with the Cup. That's obvious. In the end, what matters in modern football is who wins and we haven't known how. We haven’t been able to employ that method [nastiness, resolution, edge, etc.].

We're a young team but I don’t like that excuse because it's as if every time you lose people say: “yeah, but they're a young team”. No, no, no. We're young, but if the coach plays us it's because he thinks we're good enough. I don’t like losing the ball and having people say. “It's ok, he's only 19”. If I lose the ball, I want the same responsibility, the same culpability, as Henry. I don’t want excuses: if I'm at Arsenal, it's because I'm good enough.

Are those eulogies meaningless to you, then?

No. What we did is worthy of praise. That day, we were a team of players that don’t play often in the league, that were on their way back from injuries, that were inexperienced and very young. People like Traore and Theo. For that team to get to the final and almost win against Chelsea is impressive.

But in the final analysis, people won't look back and remember that we played with Walcott or Diaby or me. No, they'll look back and remember that Chelsea beat Arsenal 2-1. That said, when a coach gives young players the chance in a game like that it's worthwhile, even if you lose, because the experience you gain is valuable.

The things Arsenal seem to lack – edge, effort, maturity, aggression – are exactly the things you as an individual have in spades. That a 19-year-old from Spain should have so much personality and presence is really striking. Where does all this confidence come from?

From within. When I was little I always wanted to play, even if I was ill or injured and if I couldn’t play I would cry and cry and cry. I got angry with my parents even though it wasn't their fault. I always wanted to play and win and fight for everything. It's that attitude which has brought me here, allowing me to enjoy playing for Arsenal, to play alongside Henry, to have already played in the World Cup, in the Champions League final, in an FA Cup final …

That's a hell of a lot for a 19-year-old.

Man, yes. In a few years I've played seven finals, thanks to discipline, desire, spirit and the teams I've played with. I've always believed that I could do something great and now, after seeing everything that has happened in the last three years, I'm even more convinced.

It was the game against Juventus, when you got the better of Patrick Vieira, that made English fans really take notice

It was important to prove to myself and to everyone else – but especially to myself – that I could play against Emerson and Vieira and defeat them. That game really left its mark; those who had doubts began to see me as an automatic choice and it gave me real confidence.

You got Vieira's No. 4 at Arsenal. How important was that shirt, psychologically?

People said it added to the pressure, but I didn’t feel like that. The coach knew I liked that number and was happy to hand it to me, which gave me a boost. Four is my number. Not just because of Vieira, but also my idol Pep Guardiola, because I'd always worn 4 as a kid and because I was born on 4th May. Giving me the shirt was a great gesture. I was only 19 but it showed that the coach believed in me. I don’t think he would have given the shirt to someone he didn't trust, that he thought might fold.

No. 4: Fabregas. Why not Cesc, like on your Spain shirt?

I wanted Cesc, but they wouldn't let me. Unless you're Brazilian, you can't. I don't know why.

We talked about your spirit and edge. You showed that during the fight in the Carling Cup final. Commentators say they don’t want to see that kind of thing but the fans love it.

I understand that the media has to speak up against violence, I really do. But I don’t think they know what it is to be in the middle of something like that, with everything going on around you, with the pressure and the passion of a big match. It happens. And as long as nothing serious occurs, you can forget it. The fans obviously support you, though.

Is it important to do be involved, being Spanish? Because of the supposedly soft reputation of foreign players, do you feel you have to prove to English fans that you do have edge?

I don’t do it because of that. I do it because it comes from inside me, because I can't help it. People then say nice things or nasty things about me but ultimately it's me that I have to please.

You also showed a bit of feistiness when you confronted Mark Hughes. You told him you couldn’t believe he'd been at Barcelona, given the way Blackburn play.

Yes, I was angry, I felt impotent and I'd just lost to a team that didn't try to play football. I have to accept that teams are free to choose their style, that there will always be those whose aim is to stop you playing. You have to try to find a way round that and losing was our fault too, because you need to be equal to the task.

But when you see a team that refuses to play football, that only comes to defend, that doesn't shoot, or even try to shoot, in the whole match, and just defends and defends … [sighs and pauses]. I got annoyed, spoke out, and then apologised. I deserved criticism because I shouldn't have said anything, but I was wound up.

What you actually said went down pretty well – especially with Arsenal fans. They said: “he's right, what Blackburn play isn't football”. It made you even more popular.

This is something that's very clear in my mind. Every coach bases his managerial style on the way he played football, on his experiences. You look at Rijkaard and Cruyff, coaches at Barcelona, who have played in teams that have played good football, that have enjoyed possession of the ball.

If you have played at Barcelona, you expect to have developed a taste for good football. If I was coach one day, I would always ask my players to stand up for themselves by playing football. If you're going to play against a team like Barça or Arsenal of course you're going to take defensive measures, but there is a big difference between that and refusing to play football at all. I wouldn’t like to do that, ever.

You're FFT's Man of the Year and Arsenal's fans seem to think you're almost too good to be at the Emirates. They fear that you won't be here for long because Arsenal are not a big, big, club like Barcelona or Madrid.

Quite honestly, I think Arsenal is a very, very big club – even though it feels tiny on the inside. I've never before seen the passion with which people live their football here. I have Arsenal's trust and they have mine: I'm showing a lot of commitment to the club. I have tried to return all the support I've been given by Arsene Wenger and the fans by signing a long, long contract – the longest in the club's history.

I don't like saying “I'm committed to the cause” because that's the same old cliché and I don’t want to announce that I'll be here forever – who knows, Arsenal might decide they don’t want me in a couple of years – but I don’t think Arsenal are going to be too small for me. Look at Henry, who's been here for almost ten years. For me, Arsenal is a very, very big club, and one I will always love.

But do Arsenal have to prove that status to you? If Henry had gone, what would have happened? When he said he would stay, Arsenal promised to sign lots of top players, but Rosicky was the only one who arrived fitting that bill. Have they broken that promise?

But there's also Gallas and, er …[pause]. You can see the quality of our players in training and those two have been important. Hopefully at the end of the year we can make some great signings and build a very, very good team.

We're starting to see cases – such as Raúl, for instance – of players burning out having started their careers young. You've played a lot of games for a 19-year-old. Do you fear burn out?

I have thought about it on occasion, yes. It's true what you say but it also depends on the way you live your life: if you're professional, look after yourself. I don’t think about players who started at 17 and gave up or went downhill at 28, I think of those who started at 17 and finished at 34. Pelé, Maradona and Zidane all started young and played into their thirties. I prefer to have them as a model, rather than players who have burnt out.

That's quite a model to follow! Zidane, Maradona, Pelé.

No, no, no. I'm not saying that I'm ever going to be as good as them. What I'm saying is that they went started early and finished late, that they're the players to emulate. Besides, you have to have hopes and dreams, illusion, don't you?

Nick Moore is a freelance journalist based on the Isle of Skye, Scotland. He wrote his first FourFourTwo feature in 2001 about Gerard Houllier's cup-treble-winning Liverpool side, and has continued to ink his witty words for the mag ever since. Nick has produced FFT's 'Ask A Silly Question' interview for 16 years, once getting Peter Crouch to confess that he dreams about being a dwarf.

Join The Club

Join The Club