What did George Graham ever do for Arsene Wenger? Here's what...

Twenty years on from Graham's Highbury heave-ho, Jon Spurling argues it’s not just Arsenal fans who should remain eternally grateful to him for shaping the Gunners in his own vision...

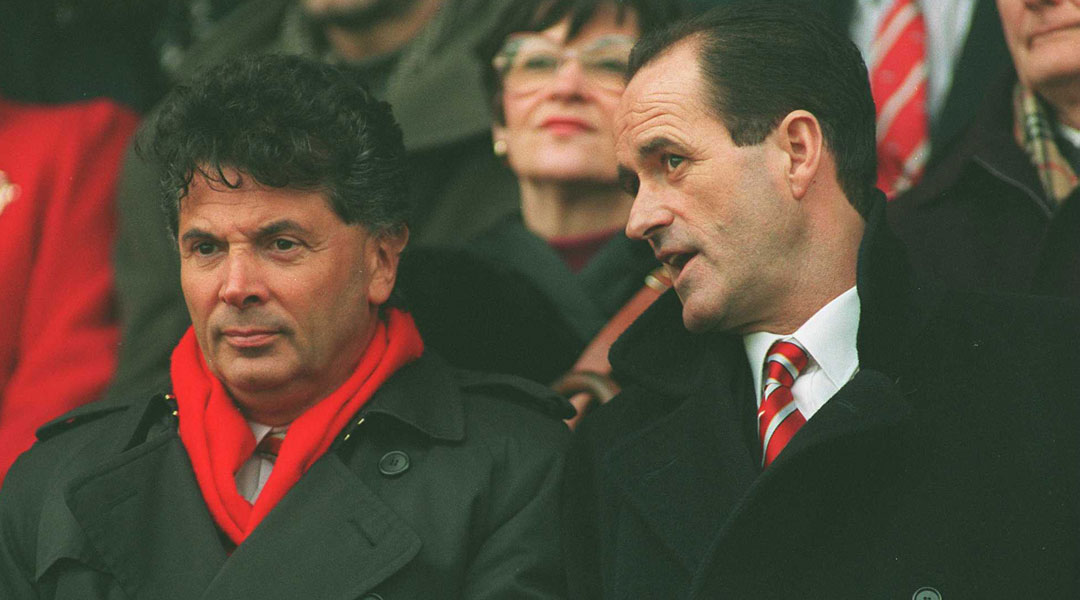

In February 1995, George Graham was fired by Arsenal in the wake of a bungs scandal. Since then, Gunners fans’ views on the Scot have remained mixed, and when he last publicly appeared at the Emirates – for the club’s 125th anniversary celebrations against Everton in 2011 – he received a muted reception.

Perhaps it’s because, decades later, the playing style of Graham’s teams appears crude and agricultural. Maybe it’s because he was caught with his fingers in the metaphorical till, or the small matter that he later went on to manage north London rivals Tottenham. Nonetheless, the divisive Scot's influence at Highbury ultimately helped pave the way for a relatively unknown Frenchman to take the club to new heights...

1) He provided a formidable backline

For the first four years of his tenure, Graham’s antennae for signing the right player rarely let him down. Lee Dixon and Steve Bould were plucked from lower-league Stoke City, and left-back Nigel Winterburn arrived from First Division new boys Wimbledon. With Tony Adams installed as club skipper by Graham in 1986, and the hugely experienced David O’Leary still as effective as ever in central defence, Graham moulded a blue-collar defensive unit through relentless and remorseless drilling exercises.

It remains a moot point as to whether Graham ever did use a piece of rope in training sessions to ensure the players operated as a unit – but the message was clear – Arsenal were a team built from the back. Their offside trap was a hugely effective system which squeezed the life out of the opposition. The Bould-Adams-Dixon-Winterburn quartet first played regularly together during the 1988/89 campaign – which ended with the decisive victory at Anfield – and remarkably it was still in place when Arsene Wenger took over in 1996.

The Frenchman explained: “The back four is the club’s rock. It is the foundation... the concrete base which keeps the team secure.” Initially, it seemed that Wenger would replace the ageing selection, but he gave them licence to roam on the pitch – and to stretch. “We would stretch before, during, and after training... then we’d stretch some more,” recalled Dixon. All four were as formidable as ever when Wenger’s Arsenal won the Double in 1997/98. “We were more mobile and forward moving than we’d been under George,” explained Winterburn, “but in essence, we were the same defenders.”

Behind the back four, goalkeeper David Seaman was brought to Highbury in 1990, much to the chagrin of Arsenal fans who resented the fact that popular keeper John Lukic was shunted out to make way for him.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

But 'safe hands' was an upgrade on Lukic, and in the days before he grew a pony tail and began to go AWOL from his goal-line, his calmness and ability to organise his defence was another anchor of Arsenal’s success.

When Wenger took over in 1996, Seaman had just enjoyed a career-defining Euro 96, and his new manager explained: “When you arrive at a club and see that Seaman is in goal, you feel relieved and grateful.” Seaman was injured for much of 1997/98, but returned as the season reached the business end. Wenger’s foreign legion was lauded for its stellar displays during that campaign, in which they conceded just 33 league goals, but it was Graham’s English defensive lieutenants who marshalled the troops.

2) He was active in helping them become a financial superpower

When Graham took the reins at Arsenal in 1986, the club was mired in debt to the tune of around £200,000. Within a year, thanks to Littlewoods and FA Cup runs, rising crowds at Highbury and Graham’s ruthless selling policy (jaded England strikers Tony Woodcock and Paul Mariner were sold, and the injury-prone Stewart Robson offloaded to West Ham), the club made a £1 million profit.

Graham’s preference for relying on youth team products and cheap imports (his first signing was Colchester’s Perry Groves for the princely sum of £75,000) meant that Arsenal remained in the black.

On the back of Arsenal’s league triumphs, vice-chairman David Dein was able begin modernising Highbury – adding the corporate boxes to the Clock End by late 1988, and announcing the opening of the Arsenal World Of Sport next to Finsbury Park tube station.

By the time he departed, Arsenal was a slick money-making organisation with an annual turnover of £20m. Graham’s appetite for signing top players may have faded by then, but as he points out: “The success Arsenal enjoyed under me helped bring huge profits to the club, added to an already-large fanbase, and meant there was now an infrastructure and commercial side which didn’t exist even five years before. It was all there for another manager to exploit. It turned out to be Wenger.”

Ironically, Wenger first appeared on Dein’s radar during a visit to London to watch Graham’s Arsenal. In the late ‘80s, the then-up-and-coming Monaco coach got lost in the maze of tunnels under Highbury, ended up in the ladies lounge and was redirected to the gentlemen’s lounge by none other than Barbara Dein, the vice-chairman’s wife. Dein and Wenger struck up an immediate rapport, with the former telling Alex Fynn – author of Arsenal: The Making Of A Modern Superclub, that he regarded Wenger as “one for the future”.

Wenger’s arrival at Highbury was some years off, but the Frenchman later admitted: “I used to watch Arsenal because I felt I could learn much from how he [Graham] organised his team tactically. I wasn’t the only young European coach to think that way.”

Graham’s disgrace after the bungs scandal was very much to Wenger’s advantage. Previously, Dein had always granted Graham a great deal of latitude (“I always told David that I preferred to work alone,” the Scot remarked) when it came to negotiating transfer deals.

Yet by the time Wenger arrived in 1996, the laissez faire era – which had seen Arsenal miss out on several transfer targets in Graham's latter days – was over. It was abundantly clear that Arsenal managers would now liaise closely with Dein over transfers, and it was the vice-chairman who was instrumental in bringing the likes of Patrick Vieira and Thierry Henry to Highbury – after Wenger’s initial recommendations.

3) He instilled an instabiable winning mentality

“You might not like me lads,” Graham told his players, “but if you work hard, you’ll win trophies and medals you can show your children and your grandchildren."

His maxims always remained the same: don’t concede goals. The bottom line is Arsenal win. Everyone fights for one another at Arsenal. We’re blood brothers, who play for the cannon on the shirt. He surrounded himself with trustworthy colleagues from his playing days – Pat Rice and George Armstrong – who shared Graham’s 'One for all' mentality and who, latterly, would work with Arsene Wenger.

The Frenchman labelled Rice and Armstrong (both Double winners in Bertie Mee’s 1971 side, who’d won 10 league games by a single goal) “true Arsenal men who understand the traditions of the club and who can pass on the message to the new breed of players.”

Under Graham, the Gunners became the ultimate flatline bullies – “1-0 to the Arsenal” became the team’s mantra – and although the quality of football was dire at times, it proved effective on many a big occasion, none more so than in the 1994 Cup Winners' Cup Final victory over a more technically-gifted Parma side.

The “1-0 to the Arsenal” philosophy didn’t simply die away when Graham departed the club. In 1997/98, Arsenal won seven league games 1-0, including the pivotal victory at Old Trafford courtesy of Marc Overmars’ winner, and a nerve-shredding single-goal Highbury win over Derby. The decisive victory in Manchester at the tail end of the 2001/02 campaign was also by a single goal.

When Wenger’s Arsenal hit a winter dip during 1997/98, skipper Adams and his fellow defensive stalwarts instigated a hastily-convened team meeting at the Café Royal during the Christmas party to emphasise to Vieira, Overmars et al the need for an all-for-one mentality, and for the former to shield the back four. “Tony was quick to point out that under George Graham, success only came when the team operated as an interlocking unit,” explained Vieira. “It was a turning point in our season, and we heeded what Tony said.”

As the infamous Battle of Old Trafford kicked off at the start of the 2003/04 campaign (Ruud van Nistelrooy’s missed late penalty meant Arsenal escaped with a 0-0 draw), Ray Parlour and Martin Keown, the two final survivors of the Graham era, were at the centre of the storm. “It certainly was a bit of a throwback to the mentality we had under George,” admitted Parlour. “Had we lost that game, we would never have been The Invincibles and it might have seriously affected our season.”

Both Parlour and Keown departed Highbury after Arsenal secured the league title – nine years after George Graham was fired. Arsenal haven’t really come close to winning the championship since.

Jon Spurling is a history and politics teacher in his day job, but has written articles and interviewed footballers for numerous publications at home and abroad over the last 25 years. He is a long-time contributor to FourFourTwo and has authored seven books, including the best-selling Highbury: The Story of Arsenal in N5, and Get It On: How The '70s Rocked Football was published in March 2022.

Join The Club

Join The Club