The 13 coolest footballers of all time (according to us)

This dazzling lot didn’t obey convention. They drank, smoked, agitated and ignored orders, but – most of all – they entertained

1. George Best

This was a man who, among other achievements, appeared on Top of the Pops, married models and dated Miss Worlds

There was something distinctly uncool about Best’s demise and passing as a result of alcoholism, but it wasn’t for nothing that he was known as O Quinto Beatle, a name given to him by the Portuguese press in 1966. The Belfast Boy was Britain’s first rock ’n’ roll footballer, combining “feet as sensitive as a pickpocket’s hands” (The Observer) with an unrivalled appetite for excess and variety.

This was a man who, among other achievements, appeared on Top of the Pops, married models and dated Miss Worlds, owned nightclubs and fashion boutiques, went to prison, appeared drunk and lewd on the country’s most-watched chat show, had pop songs and films made in his honour, airports named after him and advertised sausages.

All this, having retired from top-level football in earnest at the age of 27, his place as arguably the greatest player these islands have ever produced already secure. Wow.

2. Jay-Jay Okocha

Okocha rode a tackle, turned left, feinted right, turned left again and knocked the ball in from 10 yards, through three pairs of legs and past the diving keeper

Long before Okocha came to the Premier League, long before Bolton’s fans had t-shirts made that read ‘Jay-Jay – so good they named him twice’, long before British kids raced onto playgrounds, yelling, “I’m Okocha!” and tried to copy his dummies, flicks and turns, every German boy sat open-mouthed in front of the television and decided the one thing he wanted from life was to be like Jay-Jay.

Okocha’s Eintracht Frankfurt played Karlsruher in August 1993. With three minutes left Jay-Jay, who was barely 20, had only Karlsruher’s goalkeeper to beat. The angle was tight. Okocha shimmied to his left, feinted to his right, then turned left. Now three defenders blocked his path. Okocha rode a tackle, turned left, feinted right, turned left again and knocked the ball in from 10 yards, through three pairs of legs and past the diving keeper.

Get FourFourTwo Newsletter

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

The commentator said: “Let them fire me – I’ll now show you 100 replays of that goal.” He didn’t, but he didn’t have to. Jay-Jay was now a legend. The keeper’s name? Oliver Kahn.

3. Rivellino

In scoring the Selecao’s opening goal of the tournament, a trademark free-kick, Rivellino earned the nickname Patada Atomica (Atomic Kick)

Pele was the undisputed star, Carlos Alberto the inspirational captain and Jairzinho the top scorer, but nobody summed up the effortless brilliance and style of Brazil 1970’s ‘Team of the Century’ like Rivellino. There was something about the combination of languid left foot, rolled-down socks and porn-star ’tache that screamed ‘cool’.

The son of Italian immigrants – born Roberto Rivellino, he went by his actual name, unlike many Brazilian footballers – he grew up playing barefoot on Sao Paulo’s streets, followed by futsal, and his talent was obvious from a young age. But despite almost making Brazil’s 1966 World Cup squad as a teenager, the Corinthians star wasn’t guaranteed a starting spot by 1970, having played in only one qualifier as a substitute – he scored – as Brazil reached Mexico with a perfect record.

But coach Joao Saldanha was sacked at the 11th hour after hearing a club manager criticise his selections and threatening him with a gun. His replacement, Mario Zagallo, wanted Rivellino in the team even though he played as a No.10, a position already occupied by a certain Pele. Asked to play on the left wing, Rivellino was the final piece in Brazil’s jigsaw.

In scoring the Selecao’s opening goal of the tournament, a trademark free-kick, Rivellino earned the nickname Patada Atomica (Atomic Kick). Although his other two goals in the tournament were also thunderbolts from outside the box, there was far more to his game. “Technically,” said Carlos Alberto, “it’s hard to even talk about how good he was.”

Nothing illustrated this more than two pieces of skill in the final against Italy. First, Rivellino crossed on the volley with an almost laconic swing of the left foot for Pele to head Brazil’s opener; then, in the second half, he did the ‘Elastico’ (flip-flap). It was a move invented by Corinthians team-mate Sergio Echigo and later popularised by Ronaldinho, but it was Rivellino who perfected it. “Pele couldn’t do that trick,” he joked. “He wasn’t skilful enough.”

He was being serious last summer, however, when prior to the World Cup he bemoaned the lack of players such as himself in today’s game: “The game is too tactical now, too physical. What we once called The Beautiful Game no longer exists. But football is the game of the people. It is a chance for people to celebrate.”

4. Eric Cantona

As irascible as he was talented, run-ins with team-mates, managers and authority meant the fiery forward had six clubs between leaving Auxerre in 1988 and joining Manchester United

How was Eric Daniel Pierre Cantona different to other footballers? How was he the same, more like. Lover, fighter, enigma, philosopher, genius, actor, lager salesman – and, oh yes, he could play a bit, too.

As irascible as he was talented, run-ins with team-mates, managers and authority meant the fiery forward had six clubs between leaving Auxerre in 1988 and joining Manchester United in 1992, by which time his sporadically splendid international career was all but over. Old Trafford – and indeed English football – had never seen the like: the upturned collar, the Gallic swagger, the ability to inspire those around him.

“The place was a frenzy every time he touched the ball,” recalled Alex Ferguson, whose Manchester United side won four Premier League titles in five years with the Frenchman pulling the strings. Kung-fu kicks, seagulls, trawlers and a sudden retirement aged 30 seemed only to enhance Le Roi’s mythical magnetism.

5. Andrea Pirlo

Pirlo is one of the coolest players of his generation based on his playing style alone, but his luscious locks and beautiful beard complete the package

“One part of my job I’ll never learn to love is the pre-match warm-up. I hate it with every fibre of my being. It actually disgusts me. It’s nothing but masturbation for conditioning coaches.”

So said Andrea Pirlo in his autobiography, I Think Therefore I Play. The Italian playmaker was never one for breaking into a sweat on the pitch, instead exuding effortless elegance as he pinged diagonal balls onto the foot of a team-mate and bent free-kicks into the top corner from 30 yards.

Pirlo is one of the coolest players of his generation based on his playing style alone, but his luscious locks and beautiful beard complete the package. He even owns a vineyard in Italy and has been pictured wearing a ‘No Pirlo No Party’ t-shirt’, for goodness’ sake.

6. Dimitar Berbatov

After scoring for Fulham on Boxing Day 2012, Berbatov revealed a T-shirt with the following handwritten motto: “Keep calm and pass me the ball”

Football supporters hate lazy players. They want their heroes to leave the pitch drenched in sweat, having proven they’re willing to give their all for the club and the cause.

But there's one exception – a moody, mercurial Bulgarian that The Guardian once said “doesn’t play football. He has no interest in it. He is above it.”

Dimitar Berbatov is the one player people don’t want to see exert himself, or even – God forbid – break sweat. It’s because they recognise the presence of true elegance and cherish it. You could fill a book explaining Berbatov’s aesthetic appeal, from how nonchalantly he converts the hardest scoring chances (and wastes the most glaring ones) to the fact he looks like Andy Garcia and once admitted: “I’ve studied the way he smokes so I can hold my cigarette in the same way.”

But seven words are enough. After scoring for Fulham on Boxing Day 2012, Berbatov revealed a T-shirt with the following handwritten motto: “Keep calm and pass me the ball”.

7. Ferenc Puskas

According to Scotland legend and drinking partner Jim Baxter, Puskas’ only two words of English were ‘vhisky’ and ‘jiggy-jig’

Dubbed ‘the Galloping Major’ due to his rank in the Hungarian Army, the beauty of Puskas was that he rarely got beyond a canter, so good was his reading of the game. Winning trophies and breaking goal records galore for Honved, Real Madrid and his country didn’t get in the way of fondness for the good life, either. According to Scotland legend and drinking partner Jim Baxter, Puskas’ only two words of English were ‘vhisky’ and ‘jiggy-jig’.

This “fat little man” made a mockery of England’s remarks about him in 1953, when his drag-back and finish in Hungary’s seminal 6-3 victory prompted The Times’ Geoffrey Green to describe Three Lions captain Billy Wright as “rushing… like a fire engine going to the wrong fire”.

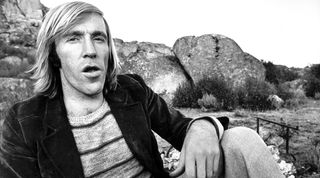

8. Gunter Netzer

He was far better-looking than any of his peers, drove (and crashed) a Ferrari, and even though he didn’t do drugs or drink, he ran a hip nightclub

In his last game for his hometown club Borussia Monchengladbach, the 1973 German Cup Final, Gunter Netzer sat on the bench for 90 minutes. His coach, Hennes Weisweiler, was so annoyed the midfielder had signed for Real Madrid that he didn’t start him.

At the end of regular time, it was 1-1. During the brief interval before extra-time, Netzer noted a Gladbach player was suffering from cramp, so he told his team-mate to come off. As the well-rested Netzer strode towards the pitch, he passed Weisweiler and casually told the confused coach: “Now I’m playing.” Three minutes later, he had scored the winner with a first-time shot from the edge of the box. Point proven.

This episode may help to explain why Netzer was seen as the epitome of cool in Germany from the mid-’60s to the mid-’70s. Outsiders may have been more fascinated by Paul Breitner because he sported an Afro and quoted Chairman Mao, but Germans knew there was no substance there. Netzer, though, was the real deal.

He was far better-looking than any of his peers, drove (and crashed) a Ferrari, and even though he didn’t do drugs or drink, he ran a hip nightclub called Lovers’ Lane. The interior was designed by Netzer’s girlfriend, a bright, beautiful, avant-garde artist.

Netzer didn’t have to sweat, toil or tackle; he had sidekicks for such mundane tasks. Netzer’s specialty was his incredibly precise long-range passing. As the German writer Helmut Bottiger once put it: “His passes were breathing the spirit of utopia.”

Netzer was always his own man, so much so that an early book about his career was called Rebel on the Ball. In January 1974, while sidelined with an injury, he was invited to the wedding of Tina Sinatra in Las Vegas. Knowing Real Madrid would never allow him to leave, he went without telling anyone.

9. Michael Laudrup

The Danish sports writer Jan Kjeldtoft once said Denmark “probably wouldn’t have won the title with him”, because the team’s style was “defending and counter-attacking”

How cool was Laudrup? Well, let’s put it this way: he was too cool to play in one of the coolest teams ever, the Danish team that stunned the continent by winning Euro 92.

During the qualifiers, Denmark’s two biggest stars – Michael and Brian Laudrup – fell out with coach Richard Moller Nielsen and quit the team. The Danes failed to qualify, but 10 days before the start of the tournament were asked to replace Yugoslavia, who had been booted out due to the ongoing war in the region.

Brian, who had returned to the fold two months earlier, travelled to Sweden with the team and lifted the trophy. But Michael, who was later named the best Danish player of all time, saw no reason to interrupt his holiday.

Maybe it was a good thing. The Danish sports writer Jan Kjeldtoft once said Denmark “probably wouldn’t have won the title with him”, because the team’s style was “defending and counter-attacking”. It was another way of saying that the silky-skilled playmaker would rather go down with all guns blazing than win with Nielsen’s defensive tactics.

10. Johan Cruyff

His combination of skill, seriousness, smart-thinking and swagger underline why, while his contemporaries Pele and Franz Beckenbauer were merely immortal greats of the game, Cruyff is iconic

Remember when, in 2005, Robert Pires and Thierry Henry fluffed that penalty against Manchester City where one player knocks the ball forward to a team-mate? What they were trying to do was copy a player for whom such an outrageous move was almost the norm.

In December 1982, Johan Cruyff took a penalty for Ajax against Helmond Sport, but instead of shooting at goal, he calmly laid the ball off for his team-mate Jesper Olsen. When the Dutch master was later asked why he’d done it, Cruyff nonchalantly said: “It’s something new, and people always like that.”

It was an answer typical of the man. Lesser mortals might have replied that they merely wanted to have some fun, but that was seldom a word that crossed Cruyff’s lips. He wasn’t in it for the fun. For him, football was serious. Like an early incarnation of Cantona, he would say strange but fascinating things, such as: “The most difficult thing about an easy match is to make a weak opponent play bad football.”

This combination of skill, seriousness, smart-thinking and swagger underline why, while his contemporaries Pele and Franz Beckenbauer were merely immortal greats of the game, Cruyff is iconic. There was an aura of mystery about him that signalled he not only played football much better than anyone else, but also knew more than anyone else.

Cruyff said things nobody had said before and did things nobody had done before – just think of that elegant little move that came to be known as ‘the Cruyff turn’.

A few years back, academics Teresa Lacerda and Stephen Mumford published a piece in which they used Cruyff’s “swift and gracious movements” during its execution combined with the “creativity” of having thought of it in the first place as an example of “aesthetic value” in sport.

And that is, of course, the final piece of the jigsaw puzzle. Being a brooding, enigmatic and groundbreaking genius is all very well, but to become a real icon you also have to look as effortlessly stylish as King Johan while doing it.

11. Zvonimir Boban

Boban became an instant hero for single-handedly defying armed representatives of what Croatians considered an oppressive, hostile state

Boban played for Milan for more than 10 years, won Serie A four times and was a member of the legendary side that demolished Barcelona 4-0 in the 1994 Champions League Final. Four years later he was the captain of the Croatian side that came third at the World Cup in France. He has a degree in history and adores the works of the Argentine poet Jorge Luis Borges.

And yet the first thing everyone remembers about Boban is that he kicked a cop. It has been called ‘the kick that started a war’, but that is, of course, a huge exaggeration. On May 13, 1990, when Boban’s Dinamo Zagreb faced bitter rivals Red Star Belgrade, Yugoslavia was already a dying state, cracking under ethnic tensions.

When violence in the stands erupted and fans spilled onto the pitch, police stormed the field of play. Boban saw one hitting a Dinamo fan, and although the officer was surrounded by six of his baton-wielding colleagues, the Zagreb captain jumped at him and kicked him in the chest. Boban became an instant hero for single-handedly defying armed representatives of what Croatians considered an oppressive, hostile state.

Boban himself later said of that moment: “Here I was, a public face prepared to risk his life, career and everything that fame could have brought, all because of one ideal, one cause: the Croatian cause.” No matter if you sympathise with his cause or not, such commitment and, above all, total fearlessness is rare. It explains why so many people still regard Boban as a role model.

12. Lev Yashin

At club level, politics dictated that he spent his entire career behind the Iron Curtain at Dynamo Moscow, with Yashin apparently shadowed by two minders whenever he travelled abroad

Known variously as the ‘Black Spider’, ‘Black Octopus’ and ‘Black Panther’, it’s that common word, ‘black’, that made Yashin stand out. But the all-black kit, worn to intimidate opponents, was only one of many things that made the Soviet shot-stopper a pioneer. He was, quite simply, the first great modern goalkeeper.

Fittingly for a player who said “the joy of seeing Yuri Gagarin flying in space is only superseded by the joy of a good penalty save”, Yashin first came to the world’s attention thanks to another Russian spacecraft, Sputnik II. The satellite enabled Sweden '58 to be the first World Cup broadcast globally and audiences witnessed a first: a goalkeeper dominating his penalty area, not just his goal-line, barking orders at defenders and starting attacks with a quick throw.

As that declaration of his suggests, though, spot-kick saves were his specialty – over 150 throughout his career – so much so that during the 1958 World Cup, the first of three Yashin played in, England’s Tom Finney decided to take a penalty with his weaker foot against the USSR, knowing that Yashin would have done his homework on his stronger one. In another group game, only Yashin’s heroics prevented a rout against eventual champions Brazil.

Two years later, having already won Olympic gold in 1956, he inspired Russia to victory in the first ever European Championship with a breathtaking performance in the final against Yugoslavia. Despite a disappointing World Cup in Chile in 1962, he bounced back the following year, becoming the first (and, to this day, only) goalkeeper to win the Ballon d’Or, thanks in no small part to his display against England for a Rest of the World XI to mark the FA’s centenary.

At club level, politics dictated that he spent his entire career behind the Iron Curtain at Dynamo Moscow, with Yashin apparently shadowed by two minders whenever he travelled abroad to ensure he didn’t defect to a big club in the west. So important was he to club and country, in fact, that the managers of both turned a blind eye to his bad habits, despite banning them among other players. Little wonder. In Yashin’s mind, it was the secret of his success. “The trick,” he once said, “is to smoke a cigarette to calm your nerves and then take a big swig of strong liquor to tone your muscles.” Of course it is.

13. Socrates

He also skippered the sexiest team never to win the World Cup, the Selecao’s Class of ’82, remembered just as much for falling gloriously short as most teams are for lifting the trophy

Where do you start with Socrates Brasileiro Sampaio de Souza Vieira de Oliveira? The headband he wore at the 1986 World Cup in tandem with that unmistakable beard would be enough to earn him a place on this list, yet he was also as deep a thinker as the Greek philosopher he was named after; a Van Gogh-referencing, Machiavelli-quoting, John Lennon-loving one-off.

He studied medicine – hence the ‘Doctor’ nickname – yet was a chain smoker and heavy drinker. He campaigned for democracy and against dictatorships, yet named Fidel Castro among his childhood heroes and sympathised with Muammar Gaddafi. He was a devoted husband and father, yet also a self-confessed womaniser. He was a walking, talking paradox who always seemed to know his own mind.

As a footballer alone Socrates was pretty damn cool, gliding across midfield for Botafogo, Corinthians and, most notably, Brazil. A peerless, two-footed playmaker and prolific goalscorer for a non-striker, he had rare technique for one so tall, perfecting the no-look heel pass and the no-run-up penalty.

He also skippered the sexiest team never to win the World Cup, the Selecao’s Class of ’82, remembered just as much for falling gloriously short as most teams are for lifting the trophy.

Perhaps fuelled by that disappointment, bemoaning the death of O Jogo Bonito later became one of his favourite subjects as a columnist. “Beauty comes first,” he once said. “Victory is secondary. What matters is joy.”

He wrote about politics and economics, too, and at the time of his premature death in 2011 he was penning a novel about the upcoming World Cup. All this, having put his medical degree – earned during his playing career – to good use by practising as a doctor once he had finally hung up his boots.

It’s fitting that the moment he described as “the most perfect I ever lived” transcended the beautiful game. In his early-’80s pomp with Corinthians, Socrates won the state championship with the Sao Paulo giants, shortly after helping to turn the club into a democracy in opposition to the military dictatorship that ruled Brazil, wearing shirts with ‘Democracia’ emblazoned across the back.

“If people do not have the power to say things,” Socrates boomed, “then I will say it for them. While I was a footballer, my legs amplifed my voice.” And how.

This feature originally appeared in the August 2015 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Greg Lea is a freelance football journalist who's filled in wherever FourFourTwo needs him since 2014. He became a Crystal Palace fan after watching a 1-0 loss to Port Vale in 1998, and once got on the scoresheet in a primary school game against Wilfried Zaha's Whitehorse Manor (an own goal in an 8-0 defeat).