The bizarre history of football-inspired names: from German Kevins to the 600 Brazilians called Lineker

Can a moniker make or break a career? How did Mighty Mouse become the father of all German Kevins? Huw Davies uncovers the game’s bizarre and at times baffling nomenclature

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

FourFourTwo Daily

Fantastic football content straight to your inbox! From the latest transfer news, quizzes, videos, features and interviews with the biggest names in the game, plus lots more.

Once a week

...And it’s LIVE!

Sign up to our FREE live football newsletter, tracking all of the biggest games available to watch on the device of your choice. Never miss a kick-off!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

English footballers are not sexy. That’s not to say they’re an uglier breed than their foreign counterparts, but while exotic imports impact English culture – from David Ginola hijacking TV schedules with L’Oreal commercials to Paul Pogba collaborating with Croydon-born grime artist Stormzy 20 years later – the favour isn’t returned. You can’t imagine football fanatics in Brazil naming their offspring after a jug-eared tap-in merchant such as Gary Lineker, can you?

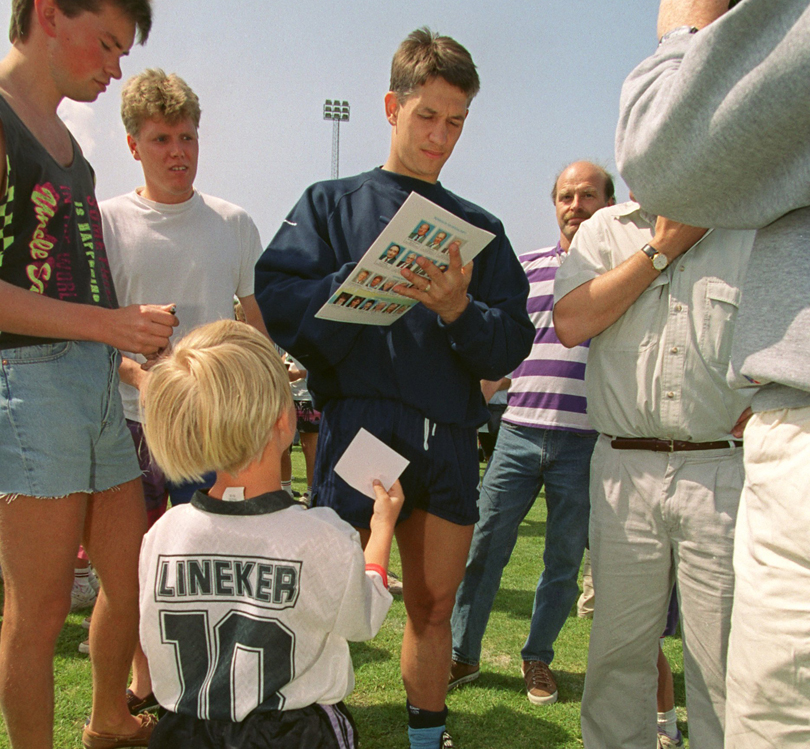

Well, actually, there are 606 Brazilians called Lineker. All were born from the 1980s onwards. Lineker is the 5,511th-most popular name in Brazil, and while that doesn’t sound like very much, it’s an Anglo-Saxon surname meaning ‘flax-grower’ which is being used as a given name in a Portuguese-speaking country. The finest striker to come out of Leicester – sit down, Emile – inadvertently lent his family name to hundreds of Brazilians, both male and female, from a genderqueer pop star to the son of Inter’s Felipe Melo.

And they play football, too. Goias-based outfit Aparecidense had a midfielder named Liniker, while 25-year-old spelling abomination Lynneeker is also back home again after a stint in Albania. Meanwhile, the midfielder Lineker Augusto tells FFT: “I once played against a guy called Liniker. Reporters were asking if we were cousins.”

But it’s not just Gary Lineker who brought a European name to the sport’s most successful nation. The Brazilian game also has, among others, a Raikard, a Rudigullithi and even a Charles Miller, in homage to the father of football in the country. The child who once inspired Bebeto’s baby-rocking goal celebration during the 1994 World Cup is named Mattheus, after Lothar; he’s now 22 and playing for Estoril in Portugal’s top tier. Yes, you are that old.

The rest of the footballing world reciprocates. Radamel Falcao was so called after the Brazilian Falcao, American frontman Edson Buddle borrows his name from Pele’s full name – his father thought that just calling him ‘Pele’ would invite too much pressure – and South Africa’s youngest-ever player is one Rivaldo Coetzee, who was born shortly after Brazil won bronze at the 1996 Olympics and christened Rivaldo Roberto Genino Coetzee in honour of three members of their squad (Genino being Middlesbrough’s Juninho).

And it’s not just Brazilians and future professionals who are being named after famous footballers. All over the world, parents sign birth certificates while replaying goals in their head, setting their child on a path to either inspiration or humiliation. Kevin Keegan’s switch to Hamburg in 1977 kick-started a trend for German Kevins that would eventually end when the name became synonymous with academic under-achievement some 20 years later.

Are these unsuspecting souls destined to live in their namesakes’ shadows for the rest of their days? Or is greatness being thrust upon them? After all, what really is in a name?

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Naming children after public figures, celebrities and even fictional characters is not a new phenomenon. Game of Thrones might be responsible for the rise in babies called Arya (280 newborns were registered as such across England and Wales in 2015), Khaleesi (68) and Tyrion (14), but Wendy caught on only during the 1950s and ’60s after Disney’s adaptation of Peter Pan.

Individualism grew in the 19th century, then exploded in the 20th. People brought new nomenclature to the canon while turning away from a naming tradition so strong, so restrictive, so dull that in 1610, 44 per cent of boys in England were called John, William or Thomas. If there was a Jacobean sprog called Maverick – more popular today than Steve – then history didn’t record it.

Naturally, football followed in tow, with individualism assisted by multiculturalism. In England, names such as Raheem and Trent have replaced the more prosaic likes of the national team’s first-ever XI, comprising Reginald, Frederick, William, Harwood, Arnold, Charles, Charles, Charles, Cuthbert, Robert and John. The 19th-century Three Lions also had a Pelham van Donop and a Segar Bastard, so maybe the world was a better place back then.

These days, many footballers bear the forename of another player. Dennis Bergkamp is a well-known example, so called as his dad was an admirer of Denis Law (but felt the single ‘n’ was a bit effeminate). Obviously, though, Bergkamp Snr had no idea that the fruit of his loins would eventually become a world-class baller in his own right.

So is it mere coincidence when a child with a footballer’s name follows in their footsteps, or are they inspired by it? Or is their moniker simply a window into a family life which, driven by a passion for the game, prioritises sporting success regardless?

I'm Pele...

“He kept me around [football],” revealed Edson Buddle, the USA international with Pele’s first name, of his father in 2010. “He didn’t force me to play. I saw his friends embrace the sport and I wanted to follow.” Edson’s dad, Winston Buddle, explained: “A positive name brings positive results. That’s why I chose ‘Edson’, to bring good fortune.” He may have been thinking of Roman idiom, ‘Nomen est omen’, or ‘name is destiny’. It comes from Plautus’ play, Persa, in which a slave girl called Lucris (‘profits’) is described as a good purchase as “the name and omen are worth any price”. Charming.

But what of the pressure that comes with being linked to Pele? At least ‘Edson’ is a slightly obscure reference; not so for several footballers christened after a giant of the game. But one recipient dismisses talk of unnatural expectations.

“I have never felt any extra pressure for having my name; it is actually the other way around,” explains Breitner – or to give the Venezuelan his full name, Overath Breitner da Silva Medina. The 27-year-old midfielder, formerly of Brazilian side Santos and now in the Portuguese second tier after relegation with Uniao Madeira, was named after two of the 1974 West Germany team that lifted the World Cup 15 years before he was born.

“It has motivated me throughout my career,” Breitner tells FFT. “As a professional footballer, I’m known for my skills but also for my name. It is far from a common name in South America. Even my teachers found it difficult to pronounce correctly, which was funny.

“When I was a young boy and came to understand football,” he says, “my father showed me videos of [Wolfgang] Overath and [Paul] Breitner. He was a massive fan of Germany’s national team, as you can imagine. He showed me some footage of that side which won the World Cup and I was amazed by it. Breitner and Overath were both world-class footballers – two real legends. It’s a shame that I was not born in the same generation as them.” If he had, what would young Breitner have been called?

Perhaps the confidence that comes with being able to write two world champions into your signature did have an impact. Perhaps it is one reason why Breitner became a professional while his brother, also in Santos’s youth team, did not. Being called Roberto Prosinecki da Silva Medina wasn’t quite as inspiring. But even if Breitner does not feel the illustrious moniker weighing heavily upon him, the man responsible for it seemingly feared that it might. For the same reason Winston Buddle plumped for ‘Edson’ over ‘Pele’, Breitner’s father decided against the name he originally chose for his child – as trying to live up to it would be ‘too much responsibility’ for little Beckenbauer. He was probably right.

“Nobody believes it”

Lineker Augusto da Silva Matos was born on July 13, 1992, a couple of months after his native Brazil had travelled to England for a friendly at Wembley. It was a game that his namesake would never forget.

Needing just one more goal to equal Bobby Charlton’s record of 49 for England, Gary Winston Lineker stepped forward to take a penalty. What followed was a Panenka attempt so hideous that the ball barely left the floor. It wobbled apologetically towards goal before being saved several minutes later by goalkeeper Carlos. Lineker never did match Charlton’s record. Meanwhile, in front of a television back in Brazil, a father-to-be presumably told his pregnant wife, “Uh, he is usually better than this. Honestly!”

So, assuming the answer isn’t ‘an especially intricate display of trolling’, why did Lineker Augusto’s parents choose that name? “Lineker is a beautiful name and Gary Lineker was an excellent centre-forward, but he was actually just one option in a list of nine or 10,” explains his namesake’s father, Ze Augusto.

“There were also a few Italian players, such as [Marco] Tardelli, [Claudio] Gentile and [Alessandro] Altobelli, and a Swede, [Peter] Larsson. I thought, ‘My kid will be a footballer – I’ll give him the name of one!’ When he was young I started training with him and I never had any doubt that he would become a footballer, and, well, he did.

“I had also been a footballer, and I was promoted to the first team straight after Gary Lineker had scored six goals at the 1986 World Cup in Mexico. He was a very good player, and I can still remember a goal he scored that helped to convince me I wanted my boy to turn out as good as him. He ran with the ball, beat two or three opponents, then stopped it to score a great goal.” So apparently it wasn’t that fluffed Panenka penalty that sealed the deal.

There is one bone of contention between father and son. “I still can’t understand why he left the ‘Gary’ out of my name,” Lineker Augusto gripes to FFT. His dad, however, decided that would make his name too long. Well, you can’t be too silly about these things.

“I’ve got a book on his career that I have read more than once,” reveals the Brazilian Lineker of his inspiration. “I wanted to know where my name came from. Most people can’t even pronounce it – and my father-in-law calls me Heineken!

“I was lucky to be named after Gary Lineker and I dream about getting to know him – I don’t even know how I would react. I’m just relieved that I was born first, because my brother’s name is Leandro. My father had a deal with my mother: he would choose the name of their first son, and she’d pick the second.”

Ze Augusto adds: “His mother didn’t like it at first, as she wanted a Brazilian name,” before saying with a laugh, “but I told her that I was the one who called the shots at home.”

This is something of a theme. Monaco frontman Radamel Falcao revealed that his mother was hesitant to give her son the name of a Brazilian footballer but that his father “made sure it happened”. The Venezuelan Breitner admits, “I’ve been chatting with my wife about naming a son after a football player. I would definitely do it. However, she doesn’t have quite the same enthusiasm.” And the Brazilian Diego Maradona tells FFT: “My father had already got the name in mind, and my mum had no choice.”

Yes, that’s right: the Brazilian Diego Maradona, who was playing non-league football for Corinthian Casuals in England, and also has brothers called Rivelino and Platini. “When I say that my name is Diego Maradona, nobody believes it,” he says. “Most of the time I need to show them my documents!” Having a famous name doesn’t solve everything, then.

There’s no evidence to suggest having an ‘unusual’ name has any impact socially. Developmental psychologist Dr Martin Ford said: “Names only have a significant influence when they are the only thing you know about the person. Add a picture and the name’s impact recedes. Add information about personality, motivation and ability and it shrinks to minimal significance.” In fact, studies have noted a positive side-effect, in that oddly-named people have got better self-control. That does support the thesis presented by one Johnny Cash, titled A Boy Named Sue.

Yet, there’s a bizarre pattern in Germany that suggests great stock is placed in what someone is called. The name Kevin rose sharply in prominence after Kevin Keegan signed for Hamburg in 1977, only to decline following his departure back to England three years later. It skyrocketed again with the release of Home Alone in 1990, starring Macauley Culkin as young booby-trap expert and product of a broken home, Kevin McCallister.

In 1991, Kevin was the most popular boys’ name in Germany. But the name later developed a social stigma of being lower-class to the point that a 2009 study by the University of Oldenburg revealed that primary school teachers are subconsciously biased against any children who are called Kevin. It has now dropped outside the top 250 German boys’ names.

Nobody knows if this awaits for the 117 English children that were born ‘Cristiano’ during Ronaldo’s six seasons at Manchester United. ‘Thierry’ also grew in popularity alongside Henry’s time in England, leaping from five or six registrations per year to over 100 in 2003 and 2004, the time of Arsenal’s Invincibles.

In the Netherlands, however, Jari Litmanen’s impact has lasted much longer. Jari wasn’t even a name there before 1992, when the Finnish maestro joined Ajax from Myllykosken Pallo –47. By 1994 there were 74 Dutch babies being christened Jari in a single year; by 1996, once Ajax had played in consecutive Champions League finals, that number had risen to 205. And it’s still proving popular 20 years later: there was another 78 in 2016.

These days, naming a child after one of your favourite footballers is especially popular among the footballers themselves – Cristiano Ronaldo did name his son Cristiano Ronaldo, after all. Last year, Javi Marquez, then of Granada, named his child Modric, which must have been awkward when his team lined up against Luka’s Real Madrid. Egyptian full-back Ahmed Nabil called his son Ozil, Watford defender Daryl Janmaat’s sons are named Dani and Xavi, while ex-Aston Villa centre-back Ron Vlaar’s are called Shane and Xavi. The 2010 World Cup Final defeat really did a number on Dutch footballers, it seems.

And then there’s the case of Enzo Zidane.

Uruguayan playmaker Enzo Francescoli spent just the one season at Marseille – in 1989/90 – but that was enough to stir the heart of a 17-year-old l’OM supporter by the name of Zinedine. “I imitated him,” Zizou later said. “I tried to copy his movements. I wanted to do exactly what he did. Everything.” Coincidentally, the book Single White Female was published the same year.

While Francescoli inspired Zidane’s playing style, right down to the Frenchman’s 2006 World Cup re-enactment of Enzo’s headbutt and red card in the 1987 Copa America Final, things went further. Enzo Zidane Fernandez was born in March 1995.

A year later, Zizou finally met his hero, in the Intercontinental Cup Final between Juventus and River Plate. Zidane was struck dumb, Francescoli recalling: “He touched me and said he couldn’t believe he was with me.” Then Zidane revealed he had named his son Enzo, and it was Francescoli’s turn to be speechless.

After the game, Francescoli donated the France international and future World Cup winner his shirt. What happened next depends on who you believe: Zinedine himself, who claims that he gave the shirt to little Enzo to wear in bed, or Zizou’s wife, in the aforementioned ranks of mothers cajoled into naming their sons after footballers. “Zinedine used to wear Francescoli’s shirt to sleep in,” revealed Enzo’s mother. “I asked him to take it off.”

Ultimately, though, it’s impossible to create a footballer simply by naming your offspring after one. Take this example. A boy was born in Leicester and named after the Brazilian great Rivelino, albeit spelled Revelino. He never made it in football. His brother, on the other hand, did: one Emile Ivanhoe Heskey.

What’s in a name, indeed.

Additional reporting: Marcus Alves, Felipe Rocha

NEXT PAGE: If that wasn't enough, discover the player who moved to Spain, where his name had a very unfortunate meaning...

This feature originally appeared in FourFourTwo magazine. Why not take advantage of our brilliant subscribers' offer? Get 5 issues of the world's greatest football mag for £5 – the game's greatest stories and finest journalism direct to your door for less than a pint in London. Cheers!

NOW READ...

QUIZ! Can you name Michael Owen's 50 most frequent England team-mates?

LIST 10 managerial appointments that would have changed the course of Premier League history

WATCH Premier League live stream 2019/20: how to watch every game from anywhere in the world

New features you’ll love on FourFourTwo.com

What did you call me?

When Romanian forward Ciprian Marica moved to Getafe in 2013, he had a slight issue – his surname was a homophobic slur in Spanish...

Did you have any idea your name was an offensive term in Spanish before you moved to the country? Had it ever been an issue before?

Yes, I knew what my name meant in Spanish even before I went there, but it had never been a problem for me beforehand. I don’t remember exactly when it was that I realised, but I wasn’t too bothered. It wasn’t something that I could influence – so I didn’t feel it was too important.

Did you get much abuse from fans in La Liga? What did you make of it?

Certainly not from my own fans, no. Getafe are a team with a wonderful set of fans and there were never any shouts from supporters that made me feel uncomfortable. Not from the the fans nor from anybody else. But there was a funny situation inside a coffee house, though. I was asked to say my name so that the barista could write it on my cup. Out of habit, I just said, “Marica!” I made the man laugh. I got my coffee, we laughed and then we went on with our lives!

Is it true you changed the name on the back of your shirt in order to prevent the abuse? Did that help?

Right from the beginning I had my first name, Ciprian, on the back of my shirt. That wasn’t because I was afraid, but because I wanted to avoid the hype and unnecessary attention. You cannot ask to be shown respect if you go onto the pitch and provoke fans. Each time I played for Getafe, there was an excellent atmosphere in the stands and I didn’t ever feel I was under attack because of my name. While I was in Spain I never noticed any homophobic attitude towards me because of my name.

Huw was on the FourFourTwo staff from 2009 to 2015, ultimately as the magazine's Managing Editor, before becoming a freelancer and moving to Wales. As a writer, editor and tragic statto, he still contributes regularly to FFT in print and online, though as a match-going #WalesAway fan, he left a small chunk of his brain on one of many bus journeys across France in 2016.

Join The Club

Join The Club