How WhatsApp changed football

It’s not just banter – instant messaging has changed players’ habits and killed the deadline-day fax. But is it all good news?

In the hands of a criminal, a knife can be used to take a life,” says the Canadian writer Gabor Maté. “But in the hands of a surgeon, a knife can be used to save a life. So is a knife good or bad?”

It’s a point that can be less dramatically applied to a simple little end-to-end encrypted messaging tool that has taken over the world. WhatsApp is mainly used for casual jabber, but it has also revolutionised communication to such a degree that we’re still dealing with its real impact, positive and negative, which has been unexpectedly far-reaching.

It’s able to inform, entertain, make us howl with laughter, send videos viral, share our most intimate thoughts and moments, do deals, market products, make or break reputations and more. In the football realm alone, WhatsApp’s wild story encompasses everything from enabling transfers and engendering team spirit to provoking murder, assisting criminal convictions and capturing people’s dying words.

For good and ill, FourFourTwo takes a journey through the mad world of instant messaging to discover its true relationship with football. Two blue ticks will appear when you finish this article...

“The piss-taking is relentless”

WhatsApp was a simple stroke of genius. Its creators invented the go-to communication method for the modern masses – and consequently football – by spotting an obvious need: people were annoyed that they had to pay for text messages, which became costly and unreliable if they were outside their contracted area, and they required a phone signal to do it. Net-dependent messaging services such as Facebook, meanwhile, either had unpleasant interfaces or were plagued with ads.

This shiny new proposition offered free messages, internationally, with no awkward registration process, nor unnecessary gubbins. Its masterstroke was piggybacking all of your existing contacts: WhatsApp used your number as your identity, so getting aboard was seamless. People also wanted to know that their messages had been sent and received – WhatsApp’s blue tick system worked a treat. It didn’t restrict the number of contacts in a group, and its encryption meant that users trusted it. And so the app exploded worldwide, almost without the need to advertise.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Launched in 2009, WhatsApp also got a couple of years’ headstart on any realistic competition. No wonder Facebook saw value in the company, which they bought for £19 billion last year as the service hit 1.5 billion users and 60 billion messages per day. The value for business was obvious. There can be company-wide groups; groups for individual departments; planning groups; social chats. And this also translated to footballers, who are generally staring at their smartphones when they’re not running around.

Logistics is one benefit. “We get team news from the manager if our training time has changed,” Frenkie de Jong explains to FFT, speaking from his time at Ajax. “And if there’s a match that everyone’s watching, people talk about it.” De Jong also used the app to inform team-mates of his Barcelona transfer in January. “I did tell them before it was made public,” he says. “We didn’t train the next day, so I thought that in case it was announced before I saw them next, I’d send them a message before they read about it in the media.”

WhatsApp groups are now – like any workplace – ubiquitous at football clubs. It has added a new dimension to the way players communicate. Foremost among them is as a vehicle for the dreaded ‘banter’, which in days gone by meant the comic genius that is Alan Shearer cutting up your socks.

“The piss-taking is relentless,” says an experienced Football League player, speaking to FFT anonymously. “Our team group at the moment is great: there’s quite a lot of funny lads, and the WhatsApp group is just an extension of the dressing room chat. We’re doing OK, so the messages sent to the group are upbeat – loads of memes, pictures and ripping. But it’s all done with respect, and I genuinely think the group has helped morale.

“I’m in a bunch of WhatsApp groups, but the club one is my favourite. The management approve, it’s also good for planning social events, and people will be pinging mad images about. It’s done nothing but good.”

For amateur teams, WhatsApp has been invaluable for its seamlessness in getting people to the same place at the same time. Players can arrange lifts or warn of problems on public transport. It’s a good tool on the bigger stage, too: coach Phil Neville uses WhatsApp with every player in the England Women’s team, and a group exists for English players abroad.

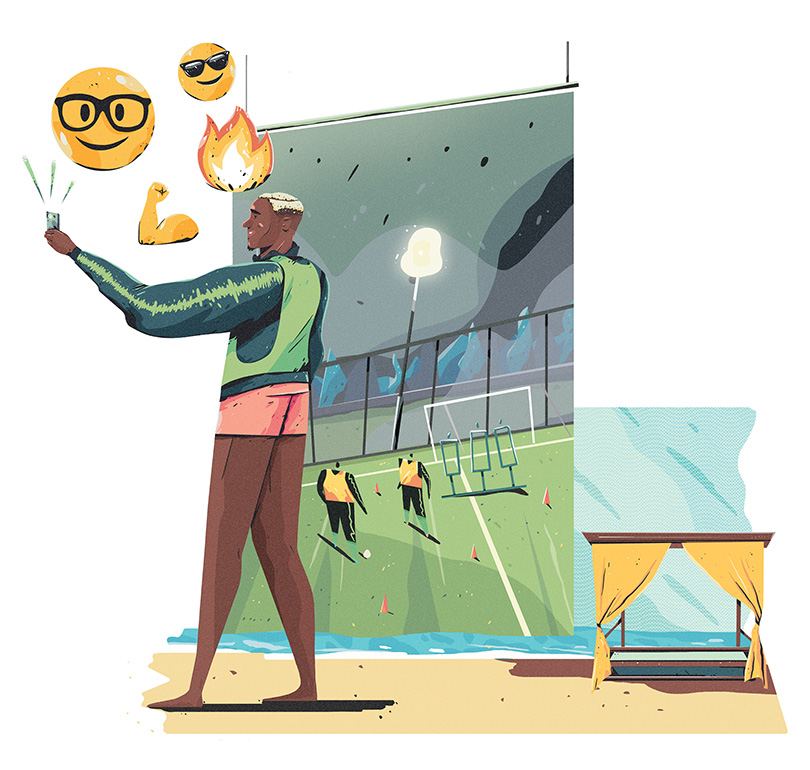

Jadon Sancho and Reiss Nelson are big fans of the app – and each other. “I’ve got love for him; he’s got love for me,” admits Borussia Dortmund’s Sancho. “We just keep on pushing each other.” Nelson, on loan at Hoffenheim from Arsenal, adds: “We message each other every day. If he’s got a game a day before mine, I’m like, ‘Sanch, you know what you have to do’.”

The format does lend itself to laughs. Last November, a conversation from the Northern Premier League went viral when Lancaster City youngster Tom Preston tried to WhatsApp the club physio, only to accidentally message team-mate Rob Wilson. Preston was complaining of a swollen right foot. “Put a sirloin steak on it,” replied the deadpan Dollies midfielder. Preston fell for it and slapped a “big fat juicy one” on his tender extremity, before sending a picture. Wilson had further counsel: “Looking at the meat, it’s quite dark. If you put salt and pepper on it, it should reduce the colouring and help with the process of recovery.” The conversation was soon all over Twitter.

Even at the highest level, WhatsApp mirth is in full effect. Gerard Pique wrote on The Players’ Tribune recently that he made a group for “guys on the Spanish national team who play for Real Madrid and Barcelona” and that last year, with Barça way ahead in the league, “All we do in that group is talk shit to one another about Barça and Real. It’s the best. Last season, when Real’s guys were winning everything, they were feeling pretty good. They were just talking shit constantly. This season, though, it’s a different vibe – their Instagram photos are looking sombre. So, I’m texting them in the WhatsApp group: ‘Come on, why so serious?!’ Then I put a crying emoji and a laughing emoji.” Harsh but fair.

Chelsea’s army of loan players are connected in a WhatsApp group with a hefty 33 names.

“It’s designed to help all players feel part of the same process,” explains the Blues’ coach, Eddie Newton. “We have a lot of players out on loan. These youngsters are big products for the club and we are regularly monitoring their progress and their games. The group helps everyone to stay closer together regardless of where they are playing. It’s a big help.

“It’s used after games, if players have scored or won man of the match. A lot of these players have grown up together and know each other well, so they feel really comfortable using this kind of platform. We’ll have our say as well, if we want to get a message through to them. This is a massive tool for us and it’s proving to be a big success.”

Whether every player agrees with that is questionable. Former goalkeeper Matej Delac shrugged, “Mostly, people from the club point out who was best that weekend,” while Izzy Brown admitted, “I don’t talk too much” and Patrick Bamford said, “Sometimes it can drain your battery if everyone is messaging each other... However, if someone does something special at the weekend, one of the computer technology guys from the loan department will send it all out.” Since then, Delac and Bamford have left the group and the club altogether.

“What the f**k is wrong with ya?”

WhatsApp has its pitfalls, as does any form of communication (there probably used to be people annoyed by offensive smoke signals). It’s not the fault of the tech, but despite encryption, leaks are inevitable, and all kinds of information can emerge which football folk would rather was kept secret.

Written evidence exists and it can come back to bite you. At Notts County, seven members of non-football staff were suspended in 2018 after the uncovering of groups in which the Magpies’ owner was roundly abused. Only one of them remains at Meadow Lane today.

Then there was Roy Keane, Harry Arter and Jon Walters’ ridiculous bust-up, in which Keane, the then-Republic of Ireland assistant boss, called Arter a “prick” and a “c**t” – while he was lying on a treatment bed – and told Walters, “You’re getting soft, it’s no wonder Dyche doesn’t play ya”, because he thought both men were hamming up knocks. Although it was an entertaining, if hardly surprising, insight into Keane’s methods (“What the f**k is wrong with ya?!”), the Ireland camp would have rather it hadn’t come out via a leaked Stephen Ward message on WhatsApp.

Furthermore, how included you feel in a group can reflect your status in the squad. Peter Crouch revealed as much in How To Be A Footballer: “The England senior squad has its own group with its own brutal logic. Get called up and you are added; get dropped and suddenly the message is on everybody’s phone: ‘Peter Crouch has left this group’.”

WhatsApp’s relationship with the pro game has also taken an extremely dark turn at times. There were the messages that formed a part of Adam Johnson’s conviction for child sex offences (more than 800 were read out in court); or the explicit image of a 16-year-old share in a players’ group by Cliftonville striker Jay Donnelly, who was sentenced to four months in prison earlier this year; or the murder and mutilation of Sao Paulo midfielder Daniel Correa last October, after he used WhatsApp to send photos of himself lying in bed with his killer’s wife as part of a “prank”. WhatsApp also captured the tragic final words of Emiliano Sala in voice messages, as he travelled to Cardiff on a doomed private plane.

As well as revealing information that should have stayed private, there is also the simple downside that anyone who has ever joined a WhatsApp group has at some point experienced: being stuck in a group with an absolute moron (and remember, if there doesn’t appear to be one, it’s probably you).

One former League One player says he’s been there. “At my previous club, it used to get on my nerves,” he tells FFT. “There was a player who wouldn’t stop messaging irrelevant stuff all day. And it got a bit dodgy, with some videos or whatever being sent that club officials definitely wouldn’t have approved of. It was nothing terrible, but let’s just say it was the sort of stuff that immature lads might send to each other.

“There was also far more negativity – unhappiness with a coach – and I can see how that can extend to managers or owners. It’s the sort of stuff that the manager is going to go mental about if they find out. But I suppose that also reflected what was going on inside the dressing room. If someone annoys you in real life, then they’re going to annoy you on WhatsApp, too.”

Dr Daniel Smith, a lecturer in sociology at Cardiff University, says that while it can be beneficial when things are going well for a team, there is no particularly weighty evidence to support the idea that a WhatsApp group will always aid players in a positive way.

“The thing about the app is that, for most people, it’s something they will use with their mates,” he says. “It’s for light-hearted chat, and it usually works best for small numbers of good friends. Like most people, I have a WhatsApp group for my old friends, where you can let your guard down, and a work one that is much more formal.

“WhatsApp groups are a place where you can often go back to being a teenager. They can be very specific; a social situation in which you don’t have to be there. You may believe WhatsApp could be something that helps to bring a group of 20 players together, and it’s an interesting hypothesis, but there’s also plenty of evidence to support that it doesn’t work.

“A lot of research has been done in military settings, asking the question of how you can get soldiers to fight for each other, to sacrifice themselves for each other. One theory is that you get them to be mates and bond down the pub. But the research shows that a lot of soldiers hate each other’s guts if you observe them down at the barracks.

“Nevertheless, they can do a job because they’ve got professional ethics, they know the drill and they know how to carry it out. They follow rules, and a personal connection is lost. It sounds cold, but it’s a better way of organising incoherent groups together, to get the job done, than being friends.

“The same will be true in football. You’ve got players from all over the world on a team, multi-ethnic and multi-linguistic. They can still work together, because they are all professionals, but giving them a WhatsApp group won’t always help. In these groups, some people will enjoy it and some won’t. Some people are quiet and some are overbearing. So, you have the same problems as in everyday life.”

Essentially, social media groups work only if everybody is totally committed to being genuinely sociable. “It’s an enjoyment of being with other people, which not everyone has,” says Smith. “When you’re playing a team sport, you’re being social but you’re also doing something else, which is committing to the rules of the game. Social media relies on playing with one another simply because you want to play. Not everyone always wants to do that.”

“Before mobiles, people had to stay near a landline on deadline day”

WhatsApp has had arguably its biggest impact in areas where the users rely on quick communication. On the transfer side of football, it has modernised an old, creaking system (think late faxes – faxes! – or Peter Odemwingie’s QPR odyssey). Daniel Geey, a football lawyer and the author of the fascinating book Done Deal, exploring the inside world of transfers, says the app has transformed the process of how contracts are signed.

“Ultimately it’s a way to communicate efficiently and securely,” he tells FFT. “Because it’s so ubiquitous, WhatsApp has become a really useful tool. When a transfer is unfolding, footballers and agents speak to each other on it; agents speak to other agents; and execs speak to each other as well.

“A lot of the finer details are worked out on WhatsApp, when before it would have been over email or phone. Voice and video options also come into play, especially when you may have foreign agents who don’t want to spend thousands and thousands of pounds making endless international calls. Now, they’re good as long as they have WiFi. It makes you available.

“Picture messages are used a lot now, too. A club might want the mandate for a player from an agent, and he can send a photo. Or, an agent and club may want to know where a player is physically, and he can send a WhatsApp pic – ‘about to get on a plane’. It can show authenticity as much as negotiate a deal.

“As well as this, WhatsApp is especially useful for negotiating final points of the commercial side,” continues Geey. “A lot of the more technical stuff is done on email, because you need to draft and redraft Word documents with in-house lawyers, but often the commercials can be done on WhatsApp.

“Before mobile phones, people had to stay near a landline on deadline day, and the fax machine would always be whirring. Email was the first revolution in the process. The next step was being instantaneous, and that’s WhatsApp – not only knowing that messages have been sent, but knowing they have been read, and hoping you’re going to get a quick response. The fact that you can also save WhatsApp messages as unread is also great. That puts it on your to-do list, which is particularly useful for agents and executives.”

The commercial potential of WhatsApp for football-related advertisers and sponsors is still in its infancy. Kevin De Bruyne recently took to his social media channels to share a WhatsApp group number that people could join; those who tapped in were linked to a ‘secret’ Nike advert starring the Manchester City dynamo alongside Ronaldinho, Neymar and Philippe Coutinho.

Such marketing has only just begun: while its founders resisted putting ads on WhatsApp, Facebook have said that they’re planning to do so. It remains to be seen whether that marks a death knell for the app or the dawn of Mark Zuckerberg’s next billion.

Ultimately, as with most social media, the best way for players – and indeed all of us – to treat WhatsApp is with kid gloves. “Any new technology will have ways of creating breakages in the way we disclose ourselves,” says sociologist Dan Smith. “People might shoot illicit images, stray into racism – things that go beyond the game. In a culture where personality rules, footballers are under the microscope. It pays to be careful.”

And we shouldn’t be too quick to castigate those who say something untoward in what’s supposed to be a private forum, says author Daniel Geey. “Whenever things go wrong on WhatsApp, I think we can be too slow to think about the wider narrative,” he tells FFT.

“There’s always a camera now when people make mistakes. And it’s very easy for players to mess up; to send a message they shouldn’t, or a picture they shouldn’t. The whole mobile era is making players extremely wary. I think it’s important to remember that we’re all as fallible as each other. When things go wrong, maybe we should give players more of a break than they currently get.”

Two blue ticks to that from us.

Then read...

LISTS 7 teams who needed a favour from a rival: title chases, drop dodges and fan-led losses

RANKED! Chelsea’s 8 worst strikers of the Premier League era

Nick Moore is a freelance journalist based on the Isle of Skye, Scotland. He wrote his first FourFourTwo feature in 2001 about Gerard Houllier's cup-treble-winning Liverpool side, and has continued to ink his witty words for the mag ever since. Nick has produced FFT's 'Ask A Silly Question' interview for 16 years, once getting Peter Crouch to confess that he dreams about being a dwarf.

Join The Club

Join The Club