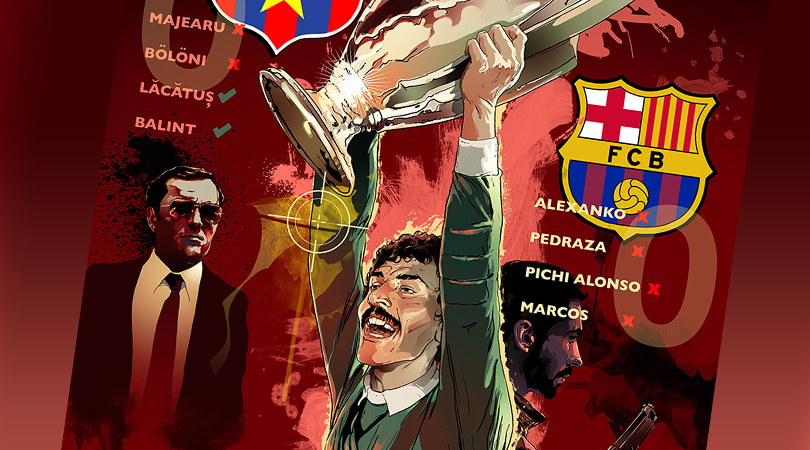

What happened to Helmuth Duckadam? “I saved four penalties to win the European Cup... but it was my last ever game”

The goalkeeper's career should have taken off after his heroics denied Barcelona in 1986. But with rumours lingering of a violent intervention by Romania’s communist rulers, he soon disappeared from view

When I was a kid, I’d always dream of playing in a big game and being the hero, helping my team to glory. But even as a child, I didn’t dare imagine it happening in the European Cup final.

Then, aged 27, even before reaching what’s regarded as the peak years for a keeper, that’s exactly what I did. I’d saved penalties in the past, against Roma and some very good players in Romania. I guess you could say that was my specialty. I stayed on after training for hours with team-mates, making bets on how many penalties I could save. All of that practice came in pretty handy.

I’d never dreamt it could be possible for Steaua Bucharest to lift the European Cup. Who could? The club hadn’t progressed past the first round in their previous six attempts. We didn’t have high expectations. We wanted to please those who were paying us and supporting us, of course, but we never imagined we could pick up the trophy.

In the early rounds of the 1985/86 tournament, we faced the kind of opponents you would never see in the Champions League today: Vejle of Denmark, Honved of Hungary and Lahti of Finland.

The dictator’s helping hand

Romania was still under communist rule in the ’80s, and Valentin Ceausescu – son of dictator Nicolae – was like the unofficial chairman of the club. Once we’d reached the quarter-finals, he told us we were going all the way. As soon as he left the room, every player fell about laughing. It still sounded impossible.

Valentin actually played a big role in our success. He took us all up to the mountains for our winter training camp. We were as tough as bulls by the spring. He helped us to train under floodlights back home, which would usually be impossible thanks to limitations on electricity consumption put in place by the communist regime. And when UEFA told us we needed to play in a change strip in the final because our kit clashed with Barcelona’s, Valentin sourced the materials and had a new red and white one specially made.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

I could write a dozen books based on my memories of that season; I would just need the patience to do it. The two games against Lahti both have special stories. In Bucharest, we played despite the entire country being flooded. At one point, the water covering our pitch was two feet high. The Romanian army, who were our patrons, helped to get the game on. Their solution? Drying the pitch with two helicopters.

The conditions weren’t much better for the return leg in Finland, as snow was piled up three feet high on the sidelines. There was a great atmosphere, though. More than 30,000 fans turned up, breaking the attendance record in Finland, all to see a team from Romania.

By the time we beat Anderlecht 3-0 in the semi-final second leg – overcoming a 1-0 first-leg deficit – confidence was sky high.

“This is my moment”

We were still massive underdogs for the final in Seville. After all, we were up against Barcelona. They thought they were at a higher level than us, that’s for sure, and they probably didn’t think we could push the game to extra time.

But as the clock ticked away, things became harder and harder for them. That fitness work really helped us, and we had some good chances too. I don’t think they were feeling very safe at the end of 90 minutes. In fact, I think we played better than them in extra time.

Our confidence and Barcelona’s frustration grew as the game wore on. It certainly wasn’t a spectacular final, but we had fantastic energy and believed in ourselves.

As the referee blew his whistle for the end of extra time, I thought, ‘This is my moment’. I didn’t care who was taking the penalties for my team, I was 100 per cent focused on my own job. I didn’t even watch our penalties – I just watched the reactions of the crowd.

We had two journalists who helped to get videos of our opponents from people working in the foreign embassies in Romania. Ironically, the only one of Barcelona’s matches I hadn’t been able to watch was their semi-final against Gothenburg, which they’d won on penalties.

That meant I didn’t know how Angel Pedraza, Pichi Alonso and the others took their penalties, but perhaps that actually turned out to be an advantage. They probably thought I knew how they shot last time, and that made them more uncertain.

More than luck

Their first penalty from Jose Ramon Alexanko was the most difficult to save. I guessed and went the right way. It was the kind of shot any keeper loves: not too high and not very powerful. If I’d gone the other way, everyone would have said he held his nerve, but unfortunately for him I guessed right. Was it a question of luck? Listen, you can dive to the right corner 10 times in a row, but if you’re not athletic or strong enough, you won’t save any penalties.

The pressure was on, as our first two spot-kicks had been saved by Barcelona’s Urruti, but I fancied myself as a penalty-taker in training and that helped me to get inside the mind of the takers.

With the second penalty, I tried to adopt a more logical approach. Pedraza was up next for Barcelona. I tried to think what I’d do if I were him. Urruti had gone left for the first penalty and right for the second. I went to my right again. Maybe Pedraza thought I’d go the other way for the second penalty, as Urruti did. I was very fit. I had good, strong legs and pushed myself to the limit to stop it.

Marius Lacatus blasted home his penalty off the crossbar, and after two saved penalties each we finally had the lead.

Barcelona’s third was the easiest to stop. Alonso must have thought, ‘OK, he’s gone to the right twice but he won’t push his luck. I’ll shoot there’. Sure enough, I went the same way and was there when the ball arrived, collecting it confidently.

Gavril Balint calmly rolled his penalty into the bottom corner to put us 2-0 up. And then it all came down to the next Barcelona penalty. Marcos had to score for them.

For me, it was a matter of inspiration. If you watch the replay of his shot carefully, you’ll see the mind games I played. First, I let him think that I was going to my left. As he was getting closer, I moved slightly to my right, then suddenly jumped left. He saw me change direction, thought I was going to keep jumping to my right, and shot weakly to my left. When you explain it like this, it almost sounds easy, but when there are 70,000 people watching you in a European Cup final, it feels a lot more complicated!

Beers from the locals

We had absolutely no idea how to celebrate. It was a total shock to us. We got the cup, went back to the hotel, drank a glass of wine and maybe some champagne, and that was pretty much it. The next day in Seville, however, was extraordinary.

Barça were a rival to fans of both Sevilla and Real Betis, so the locals kept offering us beer and asking for autographs on money or napkins. It was amazing for us, coming from a closed, communist country.

I was blown away – I was only 27 and had just saved four penalties to help my team win the European Cup. But it would end up being my last ever game at the highest level.

In Romania, there had been rumours of an attempt to get us to throw the match. This was absolute nonsense. I have no idea where it came from, but if anything we were even more motivated by the promises that the communists made us. Not that we got what we had originally been offered…

Initially they told us we would all get a Romanian Moto, then it changed to a Dacia car, then an ARO 4x4, also of Romanian production. Two months after the final, they finally gave us each an ARO 4x4. The problem was they weren’t new – we got old and used cars from the army! Our captain, Stefan Iovan, had an even bigger surprise. His ARO had been put together by a mechanic from pieces of various different cars! He wasn’t happy, although the rest of us were. The ARO was a useful vehicle for shepherds, so we sold them for decent prices.

Too dangerous to play

But then my life changed for the worse in a major way. A few weeks after the final, I was due to play in a game that was going to be fixed. The idea was to ensure our striker won the award for top scorer in the division, but I didn’t want to be involved.

Our player ended up scoring three goals, but a young lad at Sportul scored more in his last match and ended the campaign with 31 goals. That young lad’s name was Gheorghe Hagi.

For refusing to play, I was banned from Steaua’s training facilities for two weeks. There was even a trial at the ground, with Ilie Ceausescu, the dictator’s brother and an army general, overseeing proceedings. I was fined the equivalent of two months’ wages before being allowed back into the team, but the nightmare wasn’t over.

An aneurysm was discovered in my right arm. I had surgery shortly before the Intercontinental Cup final against River Plate in Tokyo. I travelled to Japan and joined up with the team, even jumping around in goal so local reporters could get pictures of me in action. I just had to make sure I always landed on my left arm.

But very quickly, the doctors said it was far too dangerous for me to carry on playing. Then I got kicked out of the army, as Ceausescu said if I couldn’t play football, I had to leave the army too. I couldn’t believe it – I’d gone from this amazing high to a terrible low so fast.

Rumours and receptions

This led to suggestions that Nicu Ceausescu, the Romanian dictator’s youngest son and brother of Valentin, had shot me in the arm, but it’s simply not true. I’ve been denying various stories about a member of the family shooting me because I’d overshadowed them or annoyed them for almost 33 years. In Bucharest back then, the hate towards the regime was strong. If someone said something in a factory in the morning, the entire city would be buzzing by midnight.

We actually met Nicolae after the final. There was a reception and he mingled with us, which wasn’t something you’d expect to happen. His words weren’t that friendly or complimentary; he was cold. He even said that if we’d been better prepared, we’d have won in normal time!

I later got a job with the Border Police and spent seven years there. These days, I’m back at Steaua as an ambassador.

People ask me if it could ever happen again, but my performance, in a way, is unique. I was in an Eastern European team, the score after 120 minutes of football and four penalties was 0-0, and a goalkeeper saved four penalties out of four. There are a lot of details which make this final a one-off, and I don’t think there’ll ever be one like it again.

Interview: Emanuel Rosu • Illustration: Gavin McBain

This feature originally appeared in the February 2019 issue of FourFourTwo.

MORE BETWEEN THE LINES… "I remember the first day that I had to kill someone... it’s you or them" – War and survival with Bruce Grobbelaar

Join The Club

Join The Club