Real Madrid's galácticos... remembered by the galácticos: Zidane, Figo, Ronaldo and Roberto Carlos recall the magic

On this day in 2000, Luis Figo left Barcelona to become Real Madrid's first 'galáctico', thus kick-starting a footballing revolution like no other. It was, recalls Ronaldo, "a term we never chose to describe ourselves" – but it was inescapable. Four of football's greats tell FFT of the glitz, glamour... and glory

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

FourFourTwo Daily

Fantastic football content straight to your inbox! From the latest transfer news, quizzes, videos, features and interviews with the biggest names in the game, plus lots more.

Once a week

...And it’s LIVE!

Sign up to our FREE live football newsletter, tracking all of the biggest games available to watch on the device of your choice. Never miss a kick-off!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

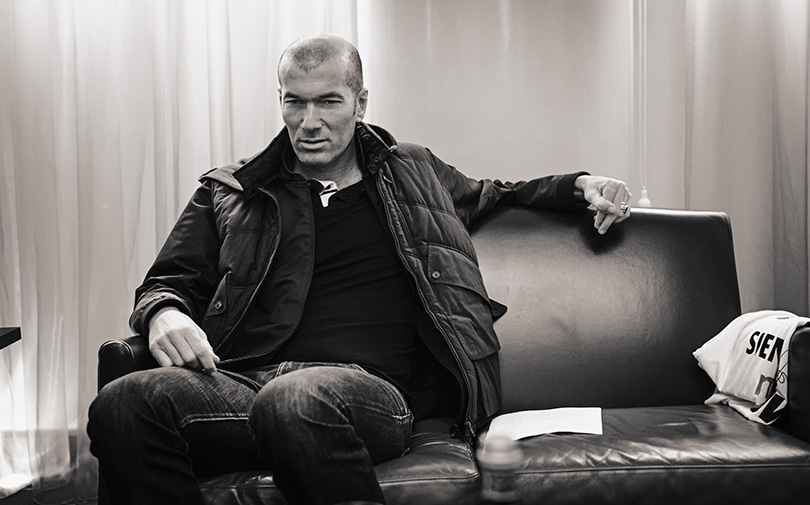

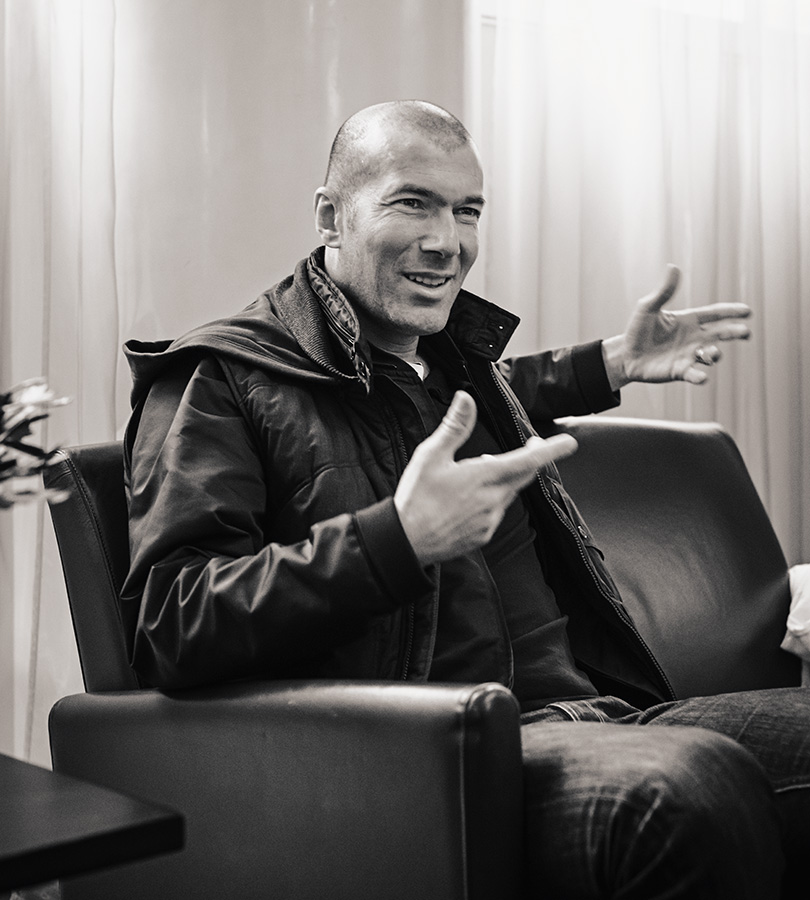

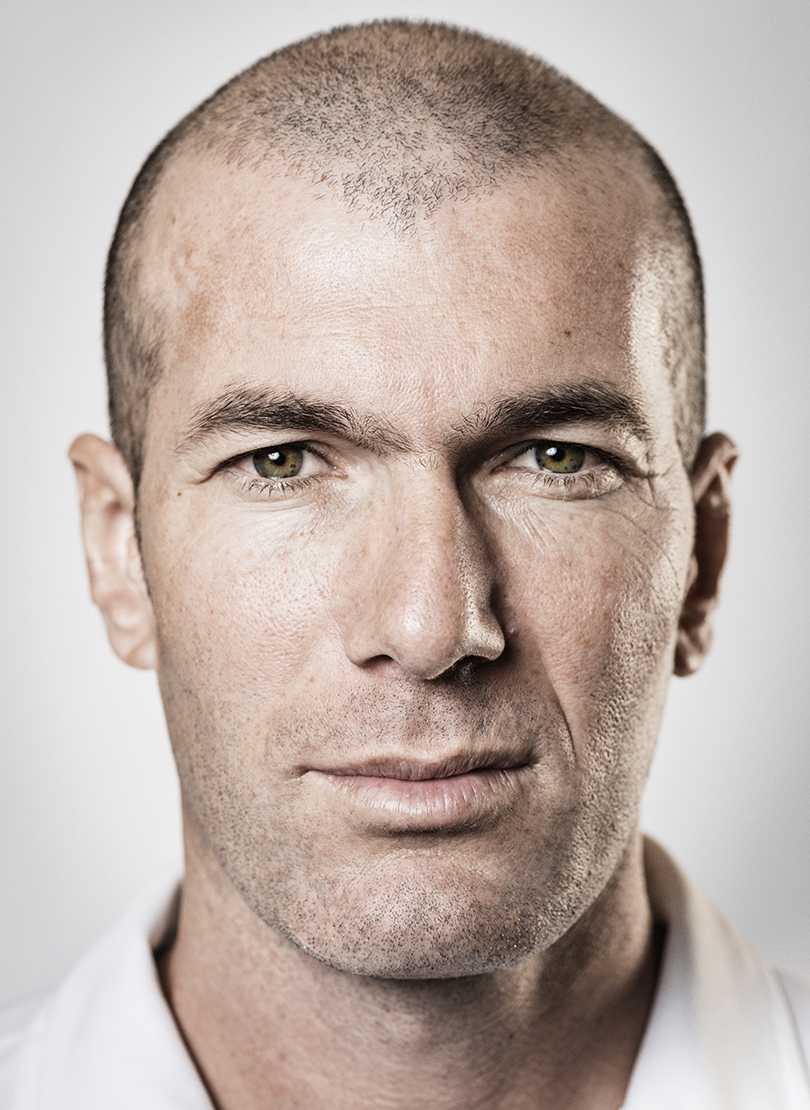

A silver car pulls up and Zinedine Zidane steps out into the mist. It is winter in Madrid. He strolls towards the door, pulling off his hat, shakes hands, and, removing his coat and draping it over the arm of the sofa, settles in. On the table in front of him sits a magazine. FourFourTwo, April 2003. Is it really that long ago? Time flies. The Frenchman picks up the magazine and smiles. There he is, alongside Luis Figo, Ronaldo, and Roberto Carlos. “I’m older now, and I’ve got less hair,” he grins.

That day in 2003, the four players posed on the pitch at Real Madrid’s Ciudad Deportiva training ground near the northern gateway to the city. These days, four gigantic skyscrapers stand in its place, towering over the Spanish capital, the land sold to clear Madrid’s €278m debt. The towers’ nicknames? Figo, Zidane, Ronaldo and Beckham.

Madrid now train just five minutes from where Zidane sits, at Valdebebas out by Barajas airport. He has just come from there. Another glance. A smile. “I was lucky to be able to play with those players,” he says. “They were spectacular players and good friends. I experienced something very special with them, at the world’s best club.”

It is a scene, a line, repeated over and over. A decade on, FFT wants to meet up with the old gang to find out what it was like, where life has taken them, to remember the good times. And, to judge by the warmth with which they all talk, those were good times.

Chasing Bobby

Meeting them all is a chase around the world. In Roberto Carlos’s case, quite literally. The first conversation was suppose to take place in Russia. Then it was Brazil. Then Spain. Then Greece. Then Madrid: first to his home to the north of the city and finally to a city hotel. In the meantime, a million changes of plans and excuses: there was even a SIM card dropped in the bath. His former team-mates giggle when they hear that he’s the last man left, that the pursuit is still on, Benny Hill-style: sounds like Roberto. He was always the hardest to tie down, as difficult to catch on the pitch as he was off it.

Yet it says something about the way that the four of them identified with Madrid that, ultimately, three of the four meet FFT in the city where they played, despite the fact that none of them are Spanish. The climate is not bad, which helps, and Zidane says he likes the mentality of the Spanish: open, happy, full of life. Figo and Zidane still live there and Roberto Carlos has a house; he was at the most recent clásico and still eats in the same restaurant he always did, devouring jamón. He remains an idol for the fans, something he is keen to thank them for.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Then there’s Ronaldo, sitting in a Kensington hotel, relaxed and charming as ever – and genuinely funny at times too. He’s preparing for a flight to China. “I’m going to play golf with Michael Phelps and Yao Ming,” he grins. It is another reminder of just how big the galácticos were. How big they still are, in fact; you quickly lose count of how many autographs he signs, and as he strolls into the lobby after spending an hour talking about those days, someone can actually be heard gasping: “Oh, my God!”

So what was it like? “Wonderful,” says Ronaldo. “I had a great time,” adds Roberto Carlos. “Good memories,” says Luis Figo. He continues: “That was a lovely time. When I look at the cover I think of good atmosphere, talent, friendship. Look at us: it looks like everyone is laughing.”

That’s because they were. It was all Felipe, the photographer, could do to keep them still for a moment. Ronaldo was, as usual, the ring leader. “Mad,” as Steve McManaman put it. “What really stays with you is the friendship,” Figo says, “even if you live on other sides of the world.” He and Zidane still meet up in Madrid; they live close by and their wives are friends too. They go to the gym together. Although Zidane adds sheepishly, “it’s been a while since I went now”. Roberto Carlos describes Ronaldo as his “brother.”

Ronaldo notes: “Zizou and I have been arranging our annual charity game for 10 years in a row now. I visit the club every time I am in Madrid: for me, that was a wonderful story which I am still living.” Roberto Carlos is harder to pin down, for them as well as for FFT. He’s always forgotten something, always dashing off somewhere, with calls unreturned. There is no reproach from his friends: that’s just the way Robi is. “We had a good time,” Figo says. “And our team marked an era.”

Fantasy football

There may never have been a team like it. They already had Raul and Roberto Carlos; Fernando Hierro too. Iker Casillas was an emerging goalkeeper, one that observers could see would be good. In fact, the moment that Roberto Carlos first recalls is pre-galáctico (and pre-Casillas): the club’s seventh European Cup, won in 1998. “We were playing Juventus and they were clear favourites,” he says. “That was so special because people were so anxious for a return to the glory days and to finally win it [32 years later]. It’s different now: these days, Madrid chasing the very best titles is a sure thing.”

“That was the turning point,” he says. Another European Cup win followed in 2000, with Fernando Morientes, Raul and Steve McManaman scoring in the final against Valencia – and it was about to get even bigger.

That summer Florentino Perez won presidential elections and began to change things. He added a superstar a summer – every summer. An already exceptional team became barely believable; the greatest show on earth. It was as if someone had cheated at Championship Manager, gathering together all the world’s best players – absurdly talented, absurdly famous. When Hierro, the club’s captain, told FFT “of the 10 best players in the world, we have five”, he was not wrong.

“The best players in the world have to play for Real Madrid,” said Perez – and mostly, they did. At the time, Madrid boasted five of the previous six winners of the FIFA World Player award. There may never have been such a monopoly in the market, a team that bought so many of the world’s best. Pick a dream team at that point and half of them at least would be Madrid players. In fact, that was pretty much what happened: when Madrid celebrated their centenary in 2002, they faced a world select XI at the Bernabeu. Supposedly the very best players on the planet, handpicked from every club on earth, they were not as good as their hosts. That night, the biggest names lined up in white.

In between the teams, singing Madrid’s anthem, was Placido Domingo. Madrid visited the Pope, the United Nations and the King. Magic Johnson came to play with their basketball team. They wanted to be associated with the men who would later get called galácticos as much as the other way round. It was impossible to avoid the excitement; the sense of being in the middle of something special. Every day from through the metal bars of the training ground, hundreds of hands reached out to the players, fans screamed, desperate for autographs or pictures.

Hard days, harder nights

They were like The Beatles. “Sí,” concedes Figo. “It was incredible. It was all blown up so much. It was like a fashion.” “Madrid made me world famous,” Roberto Carlos says. That was not always a good thing: there was pressure and attention everywhere, but mostly it was fun. “A typical night out? We would basically go round to each others’ houses,” the Brazilian smiles. “We all had kind of discos at home. We basically wanted to have fun but it would be difficult to do that in the public eye, in front of paparazzi and people who wanted to take advantage. Of course were there women – we were mostly single. We wanted to have fun but we wanted to play for Madrid even more, so it was not over the top.”

It was fun on the pitch, too. “We might have been more of a team before then but there was something about that side that meant you went onto the pitch thinking: ‘I wonder what they’ll come up with next’,” remembers former right-back and FFT columnist Michael Salgado. “I enjoyed playing in that team so much,” says Zidane. “The opposition might score two, three goals ... nowadays, if that happened, you’d say: ‘we’re going to lose’. But we didn’t. No pasa nada. They scored two? We’ll score three. It was fun.” Roberto Carlos puts it in simple terms: “We were all like kids enjoying ourselves out on the pitch when we were together.”

He enjoyed it especially: Roberto Carlos tries to talk about himself as a defender, describing himself as “not nearly so spectacular as those guys”, noting how an “offensive team needed a defensive player with speed and stamina”, and even using the words “stable” and “useful” to define his role. But it just doesn’t wash: here was a left-back playing anywhere but at the back. And not spectacular? Pull the other one. He was a monster, racing round the pitch, monster thighs pumping, practically bursting the ball every time he took aim.

McManaman joked that he was “deformed”. Actually, he is not far wrong. “I was always muscular,” the Brazilian says. “But at Madrid they (his thighs) got even bigger because I needed even more power and speed. I have bought special trousers ever since I could afford them. Before then, I just got the sides and hoped they would fit.”

Not that he was the star, or at least not the only star. Everyone agreed on who the greatest talent was. Well, almost everyone. “Only Zidane would say that Zidane was not the best. We would joke about the fact that he was the only one who didn’t think he was the most skilful player of his generation,” Roberto Carlos says. Whenever David Beckham was asked about the Frenchman, there was a kind of reverential hush about the way he answered, almost in a whisper. “Zidane was the best,” Ronaldo agrees, “no doubt about that. Everything came so easily to him. His control was incredible. He was the best player I played with.”

The feeling is mutual and Roberto Carlos is proven right: “Ronaldo had the most talent,” Zidane says. “Ronaldo! He didn’t need to train, the cabrón!” laughs Figo, destroying at a stroke Roberto Carlos’s politically correct insistence that you couldn’t be any good if you were a little on the laid-back side. “He was so good that he didn’t need to train.” Zidane agrees: “Once in a while he didn’t fancy training, but the thing is that Ronaldo was such a good player and such a good person that in the end no one really minded.”

“I remember a game at home when the president came along with some politician who was important: ‘Ronnie could you run a bit more?’ He says: ‘Presi, you pay me to score goals not to run.’ So of course he goes out there and he scores. Only Ronnie could do that and he was the only one who the president would say something like that too.

“He was just so likeable. That was a good thing. If we’d told that story at the time it would have caused such a stir but, looking back, that was one of the things that made Madrid so great: it was natural.”

Goofy greatness

You can still see it now: there is no pretence with Ronaldo; he is very natural, honest, and ultimately just extremely likeable. Figo insists that Ronaldo is listo, smart. There’s definitely a spark behind the goofy grin: he speaks good English and has proven to be an astute businessman. He is proud too, more determined than it sometimes appears. But there was something almost childish about him, about the sheer enjoyment. “He lived each day,” Figo says. McManaman describes him as the team’s joker.

“The joker?” Ronaldo laughs. “Hmm. There is one that I can tell you about my golf buddy Macca. After we won the league for the first time [in 2003] everyone went out to celebrate. We drank, we ate and we danced. The next day we had to be at the town hall at 9am for a very formal event to commemorate the success. Everyone was there...”

Not quite everyone. Ronaldo prepares the punchline. “Guess which two players were the only two that didn’t make it?” he grins. “We were still out celebrating.” McManaman might have been in trouble, had it not been for the fact that he had the best back-up imaginable. Instead, it was just funny.

Balancing act

The coach was, of course, Vicente del Bosque. It was his job to make it work; to create that kind of natural atmosphere – and to build a team that functioned. That included playing Zidane in a false left-sided role that, with Roberto Carlos bombing past up the line, gave him freedom to drift into the centre. Del Bosque was under no illusions, describing himself as an “employee”. He knew that the policy was not his to decide but to work with; he was aware too that certain players enjoyed an untouchable status. McManaman recalls the coach effectively telling him that his hands were tied on team selection.

In an unnatural situation, Del Bosque kept the balance. He helped to mediate with those who felt they were getting too few opportunities, and maintain an equilibrium between the hard work and the relaxed, easy atmosphere that he thought conducive to harmony. Often that meant keeping a discreet, low profile: “We hardly see him,” McManaman remarked to FFT. He had what the Spanish refer to as ‘left hand’. But tactically, too, he found solutions. When it really mattered, he would surprise opponents with some clever shift.

“He spoke little but what he said was the right thing and at the right time,” Zidane recalls. “I agreed with what he said. I remember that when I got there, I was a No.10 but here I never played there and he said: ‘You’re going to play as a 10 still. When you have ball, come inside. But without it, you go out to the left.’ That was for the balance of the team. He spoke little but well. Perfect.”

“Everyone liked Del Bosque,” Figo adds. “He was very sensible. He knew how to manage the group very well. He’s not pesado; hard work, heavy-going. We lived great moments with him and I have real affection for him. I admire him. It was a fantastic experience to work with him.” As Roberto Carlos has it: “Vicente was what the club needed, because he knew the club well and got the most out of the players without reinventing the wheel. We won two Champions Leagues with him and he was always very simple in his instructions.”

The club captains Raul and Fernando Hierro were vital too. “Raul trained the best. He transmitted that ilusión that at Madrid you can make it but you can’t do anything without working hard,” says Zidane. “And Fernando was fantastic. “He was the only one that Roberto Carlos listened to, for example. Roberto did whatever he wanted. He was here, there and everywhere and when Fernando said ‘Roberto, here’, he listened and he came back. Fernando was the only one; he was also the one who did the most to keep us together as a team: when I arrived, he was there. ‘If you need anything...’”

The Makelele role

And then there was Claude Makelele. In his column for FFT, Michel Salgado cited him as the player who made it all work, someone that Madrid only managed to adequately replace with Xabi Alonso almost a decade later. “We did more or less what we wanted; he was the one that allowed us to.”

“Everyone was important, the team: the 11 were important. Even more so, because they create balance in the dressing room,” Figo says, starting to giggle. “But Makelele was the only one who ran backwards, towards his own goal!” Zidane adds: “Our philosophy was always to go and try to win games, always attack. “Makelele was the only one who always, always, kept his position; he never went. Never. He knew what he was doing. He was the reference point for the team.”

But then it was Zidane, Figo insists, who made the team play. And boy could they play. It was erratic at times but even when they played badly, there was something. Some moment, some piece of skill, a flash of genius, that made it worthwhile. There was no ticket like it: suddenly Madrid were selling out every game. That had not happened before. Everyone wanted to see them, to witness this – there was something romantic, childish about it. They were a fantasy football team. “People enjoyed just listening to the PR announcer read out the starting XI,” Salgado says. Those names: Figo, Zidane, Ronaldo... never before had so many of them been brought together.

Going with the Flo

The revolution started with an electoral promise; the news broke on the day that the current president Lorenzo Sanz was attending his daughter’s wedding. Suddenly, the media was onto him. What did he think about his opponent’s claim that he would sign Luis Figo if he was elected? Sanz laughed it off. There was no way that Figo was going to leave Barcelona where he was an idol. But over the next few days it became clear that Florentino Perez was deadly serious. And, although Figo denied the news in the media, Perez knew a way of making it happen.

He had spotted that Figo’s official buyout clause stood at 10,000 pesetas, the equivalent of £38m. Paying that meant paying a world-record transfer fee but it also meant leaving Barcelona with no way of blocking the move: league rules meant that once the money was deposited at LFP HQ, they could not resist. All it would take was Figo’s acceptance – and Perez had a way of gaining that too. The Portuguese winger’s contract negotiations with Barcelona were not going well; he felt insulted at the offer made.

The door was ajar. Perez offered Figo’s agent Jose Veiga 400m pesetas to sign an agreement binding him to Madrid in the seemingly impossible event of his election victory. It looked like money for nothing and the deal would help force Barcelona’s hand, pressuring them. If Perez won, the only way out of it was to pay a huge penalty clause – but there was no way he was going to win. Sanz had just delivered two European Cups in three years after a 32-year wait.

But Perez did win. The Figo Effect was a big part of the reason why: polls had shown that he was the player Madrid fans most wanted to see in white. Just over a week later, the day after Barcelona’s own presidential elections had come to an end, Figo signed for Real Madrid. He wasn’t smiling much. The truth is that he did not seem all that happy to be there.

The question, then, is inevitable. Why join Madrid? “I didn’t feel recognised for what I was giving the club [Barcelona],” he says. “I felt like I was giving my all and I didn’t feel from the directors the recognition that I felt I should have had. I told them that, I was clear about it, and they took no notice. They thought I was bluffing. And then things started taking the direction they took.”

“That was [an] uncomfortable [time] because there were doubts, there were difficult moments. Maybe it wasn’t very, very, very clear because it did not depend only on me. And so that made it all hard,” he continues. So, did you actually want to come? Really? “Well,” he says, “it started with anger and it ended up being real. But in the end it was the right decision. In the end, yes.”

There were no such doubts for the men that followed him. Next came Zidane, then Ronaldo. And the season after that, David Beckham. “The key,” Perez always said, “was the players wanting to come.” After that, negotiating with the clubs was easier. And with each passing player, so was negotiating with the players; David Beckham makes no secret of the sheer seduction of Madrid: Raul, Roberto Carlos, Ronaldo, Figo... Zidane! “All those great players.”

The napkin

Not long after Figo signed, Zidane found himself at a dinner with Perez. A napkin was passed round the table until it reached the Frenchman, with a note scrawled on it. “Do you want to play for Real Madrid,” it said in Spanish. Zidane took a pen and wrote, in English, “yes”.

There’s something almost embarrassed about the way that Zidane tells the story. “‘Yes!’ It wasn’t normal paper and it wasn’t easy to write on. I could have said ‘ouis’ or ‘sí’ ... I really don’t know why I wrote ‘yes’. I was happy. Enough to say to myself: ‘I’m going to speak in English’. I wanted to join Madrid because they were the biggest club in the world. It’s true that I could have played for Barcelona [a few years earlier when Johan Cruyff was keen to sign him] but it was always my dream to play for Real Madrid, to wear that white shirt.”

The very presence of Zidane and Figo changed things. “It was important to know that all those fantastic players were there,” Ronaldo admits. “I was an icon at Inter and I had just won the World Cup, plus my contract was good in Italy. But I wanted to go. I had to pick a fight because I wanted to play for Madrid. For Inter supporters it was radical and I understand that but I really had to follow my dreams. And when I turned up, it was wonderful. I didn’t feel intimidated at all: all these great players and I got a fantastic reception. It would be difficult to make it work but we did.”

Beckham’s position was similar. Even if it was Barcelona who announced that they had reached an agreement to sign him, they had no chance. “I never spoke to anyone from Barcelona,” Beckham told FFT during his time in Madrid. “When I found out that Man United wanted to sell me, I was annoyed. They wanted to make the decision for me and the only thing that I wanted to do was make my own decision. Barcelona is a great club, it was obviously an honour to be mentioned by them and [presidential candidate Joan] Laporta is a nice person, a good guy, but I had always said that if I ever had to leave United – which I never thought I would do – then I would be going to Real Madrid. And I would decide my future.”

It didn’t take them long. Ronaldo scored within a minute of coming on in his debut; Beckham found the net after 124 seconds of his league debut. But neither Ronaldo nor Beckham, like Zidane and Figo, makes any bones about the pressure they were under. At one point Ronaldo had to request that the media leave him and his family alone. He had eased the tension a little on Figo and Zidane – “with each year it got spread out,” the Frenchman smiles – and the following year he would publicly declare with a grin: “I’d like to thank David from taking them off me.”

Paparazzi followed Beckham everywhere. He would drive home in convoy, deliberately turning down narrow side streets, the second car stopping as he pulled away to escape. There were dummy runs and security. At times, it got too much. Here was the other side of the galácticos – as if the pressure at Madrid wasn’t big enough anyway.

Price tags and pressure

“Unless you’ve been inside Real Madrid you’ll never know how gigantic everything is there,” Ronaldo says. “It is the most important club in the world and everyone is talking about it – even if they don’t know what they’re talking about. Winning something here is huge; failure, of course, is even bigger.”

For Zidane, that weighed heavily. His first three months were, he says, “difficult”. Madrid were not winning – except when Zidane didn’t play. There were some wondering if he was really worth the money. After all, his transfer fee had been another world record. And, frankly, he wasn’t playing well.

Michel Salgado says that Zidane was even thinking of giving in. He had started to question whether coming to Madrid was such a good idea after all. “It does cross your mind, Zidane admits: ‘Maybe I’ll go.’ The first three months were difficult. The media chased me everywhere, there were photographers everywhere, and I thought ‘what is this?’ I wondered about it. But it’s a passing thing. You train and you play, and it passes, team-mates and people at club told me. In the end, everything passes.”

“If Zidane had pressure, what happened to me had never been seen,” Figo insists. “Madrid has extraordinary dimensions. Radio, papers, TV, interests. For me it was worse than Zizou because I came from a rival.

“My first year the club was still being structured, a new president, an electoral change and so on, and I felt like I had to be in the press every day. You have to justify your performances after you have been the most expensive player in the world. You go onto the pitch and you’re not thinking about whether you cost 50 or 60 million, or if you earn one thousand or two, but subconsciously you do feel the pressure of that. Sometimes it’s a good thing, though. The pressure keeps you alert, awake.”

Welcome back

Never more so than in the Camp Nou. The clásico is huge these days, the tension, the sheer depth of hatred, and of course the quality. It can often feel like it has reached a zenith – or perhaps a nadir, depending on your point of view. But Roberto Carlos insists that it was bigger then.

“Part of the animosity is gone these days,” he says. “Maybe I say that because in those days Madrid was the team to beat in Europe and I was still playing. But I think in those days it was more of a fight. They know each other of the pitch and the teams are even more international. Nowadays it is more of a friendly. Very well played, beautiful, but friendly.”

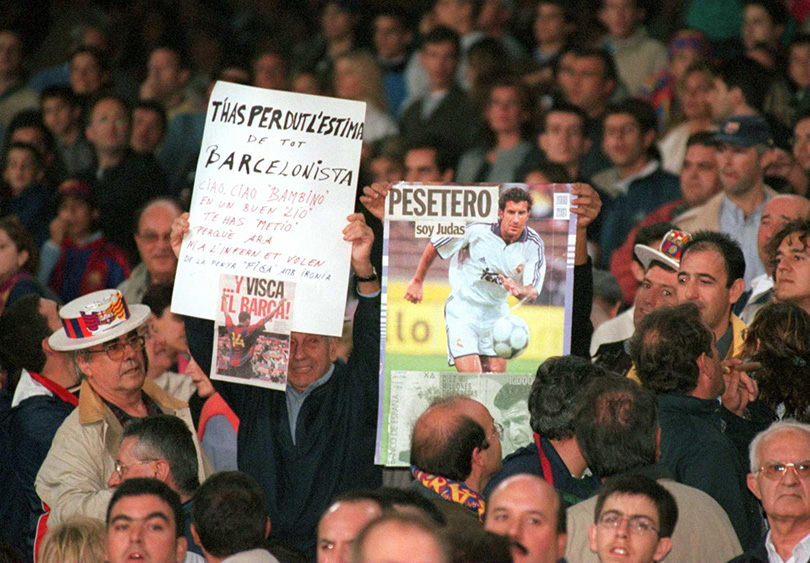

Calling it a friendly is a fairly dramatic exaggeration but Luis Figo might agree. When it came to him, ‘animosity’ stops a very, very long way short. In his first season, he could hardly function when he returned. He was ‘welcomed’ back as Judas. Golf balls and coins and bottles were thrown at him.

He says: “I must be one of the very few sportsmen to have had to perform with 120,000 people against me – and focused on me, not the team. It’s a strange situation when you go back there, to a place where you have been for five or six years, and you find yourself in a new situation. But I had lived lots of situations on the edge and I like the fact that that makes you alert.”

“My concern wasn’t the atmosphere but that something beyond the pitch could happen. It was so heated up by the Catalan press that I was worried that some madman might lose his head.” In his third season, the hatred still having not subsided, some madman did lose his head. So, famously, did a pig.

Among the objects thrown at him was the head of a cochinillo, a suckling pig. “I didn’t see it. I didn’t realise: there were so many things that I didn’t notice. I saw it the next day in the press,” Figo says. Then he burst out laughing: “If I had seen it, I would have eaten a bit! Time for an aperitivo. It never even enters your head that someone could go into the stadium with a cochinillo.”

“Or a bottle of whisky.”

Ownership and expectations

With every year came a signing, and every year belonged forever to that signing. The summer was part of it, almost as important as what happened on the pitch. It was all about ilusión, the hope, the expectation, the excitement. But then they had to deliver, and for all of them there was redemption and relief as well as joy.

Figo’s Year ended with Madrid storming to a league title, the Portuguese leading his side as he did all year to a hammering of Alavés. Ronaldo’s Year ended with him scoring on the final day to clinch the league title. “No matter how experienced you are, you never quite realise how big it is to write your name into the history of this club,” he says. And in between them, Zidane’s Year ended with the European Cup. This was the pinnacle – and in Madrid’s centenary too.

No club is as synonymous with a trophy as Real Madrid are with the European Cup; it is the trophy that defines them. So much so that they need not even name them now, just number them. They had waited 32 years to win la séptima, the seventh. The eighth came two years later. Now came the novena. Ask Real Madrid’s players for their best memory from the galáctico era and, curiously, it is this game that most pick out: a game that came before the stars were all there, before Ronaldo and Beckham.

“To me, winning the European Cup in 2002 was the best moment,” Roberto Carlos says. “Very few teams could match that. Zidane was proving to be one of the best ever, Raul was in fantastic goalscoring form, Figo was still one of the best in the world. We beat Barcelona in the semi-finals, defending champions Bayern in the quarters. It was Madrid’s centenary year: a dream come true. Then Ronaldo came the following year and it got even more marvellous.”

Figo had not won the European Cup. Nor had Zidane: it was the one thing he had not won. Ronaldo still hasn’t, becoming part of a great quiz question: players who have been at four European Cup-winning clubs without winning it themselve (Inter Milan, Milan, Barcelona, Madrid).

It hadn’t been an easy year. If it ended with the best moment, 2001/02 also contained the game that most, Roberto Carlos apart, recall as the worst: the Copa del Rey final at the Santiago Bernabéu on Real Madrid’s 100th birthday; the game specially shifted by the Federation to coincide with the date of the club’s foundation.

“It was all set up for us to win,” Zidane says. Instead, he describes that night as “horrible”. Instead, it was the north stand that celebrated the night away, 20,000 Deportivo La Coruña fans ironically singing ‘Happy Birthday to you’ at their hosts.

Winning the cup was an obligation: McManaman recalls the team feeling like they were on a hiding to nothing. Deportivo won 2-1. “I remember Diego Tristan... sometimes he produced amazing performances and that night was one of them,” says Zidane.

Figo came into the game struggling with an ankle injury and came out of it struggling even more. The memory still hurts. “That was the worst moment for me. I played injured and I suffered a lot after that. Losing at home was hard. I had an important injury and it was badly diagnosed, I had to take a pain-killing injection to play the final and it affected me for the rest of the year.”

In truth he shouldn’t have played. So why did he? “It’s a final,” he replies. “I thought it was a sprain but it was more than that. I suffered a lot. I played a bad World Cup and the ankle wasn’t right. I paid a very heavy price for that ... and in the end we didn’t even win.”

Zizou’s swing

Europe and that goal made up for it. “It was,” Roberto Carlos says, giggling, “the perfect assist.” Zidane grins: “Perfect, yes: I’ll testify to that. Where do I sign?” Bombing up the left wing, the Brazilian hooked a high, high ball into the air, looping towards the edge of the area. It was aimless, a ‘watermelon’ to use the Spanish phrase. But it turned out rather well: an ‘assist’ so ‘perfect’ that Zidane even had time to think. But think what?

“What I’m thinking is: ‘I’m going to shoot’,” he says, looking up at the ceiling, turning his shoulder, doing the actions. “I shift sideways and I think: ‘I’m going to shoot.’ I looked across to see where the goal was. I had time. I know I’m going to hit it first time and… whoosh! When it went in, I felt so much happiness. I ran off shouting, and in Spanish too. Take that! Take that! Take that!

“That was the thing I needed at this club, a great moment. The trophy I didn’t have was the Champions League. I had lost it twice with Juventus, one of those against Madrid. And when a club buys you and pays 78 million, it’s because you have to do something very big. The first three months were difficult: the media chased me everywhere, and I thought ‘what is this?’ That goal was perfect. People say: ‘Well, he cost a lot but he won the Champions League.’ Lifting that European Cup was the best moment for me at Madrid.”

“The king of Spain was in the dressing room and it was as if he was one of us. It’s the king! When you’re there, that’s when you think: que bonito! Everyone’s laughing and joking. People outside wouldn’t imagine it.” The goal became a symbol; the perfect culmination of a difficult year, the coronation of Zidane. He had become one of Real Madrid’s greats, some elevating him to the status of the game’s five greats, with Pelé, Maradona, Di Stéfano and Cruyff.

Dry your eyes mate

Zidane played his last game for Real Madrid in May 2006, a 3-3 draw against Villarreal at the Santiago Bernabeu. Five years on, one of the greats was bowing out. On the giant screen at each end of the stadium, videos showed his best moments as a Madrid player. That goal from Glasgow was everywhere, the silhouette that became so symbolic, foot up near his ear connecting with the perfect volley.

There were banners all over the stadium. Gracias. Merci. One pleaded: “Referee, don’t blow the final whistle: that will be a signal for Zidane to leave us.” On the players’ shirt, stitched below the Madrid badge was: “Zidane, 2001-2006.”

With three minutes to go, Zidane was withdrawn to a standing ovation. He disappeared into the tunnel, where he waited silently until the final whistle. “That was really... mal, mal,” he says, struggling to find the right word. “I had a bad day. Right from the start to the end, I just wasn’t there. I was thinking: ‘It’s over’. ‘That’s it’. I was thinking so much about the end, about what happens next, about the fact that it was my last game at the Bernabeu. And it’s weird but I cried before the game. That can happen to people, but not to me.”

He puffs out his cheeks. “Pfff... before the game, and after it too. We went to eat, my whole family, maybe 50 people. And the presidente came to see to say: ‘Thank you for everything you have done.’ It was a lovely gesture.”

Zidane’s departure signalled the end, a break from all that. Figo had gone the previous summer. And by then, the president Florentino Perez had already walked away, resigning after a defeat in Mallorca in February. There would be elections in the summer, a change of régime. Ramón Calderón came in and Fabio Capello became manager. Ronaldo left seven months later, heading off to Milan. “Capello took away my enthusiasm for the game,” he says. And on the final day of the 2006/07 season, Calderón’s first in charge, Capello’s too, David Beckham and Roberto Carlos bade farewell. They did so with Madrid’s first league title in four years.

When Zidane left, he still had the World Cup to look forward to, and he performed brilliantly in carrying France to the final. Some wanted him to change his mind and continue but he was not for turning. The Frenchman looks extremely fit. So in fact does Figo, with whom he still plays padel in the gym near to where they both live. But it’s not the same. “You miss the adrenaline of playing,” Zidane says. “You’ll always miss that.”

“You miss the football but you don’t miss the rest of it. In the end, you tire of it. All that time locked away in your room in a hotel. You can’t come out because there are people everywhere. I couldn’t take it any more. By the time you’re 34 or 35 you can’t do it any more. At 20, 25, it can seem fun but in the end I left it because I couldn’t take it any more. You’re always in a hotel because you’re playing every three days. It’s part of a footballer’s life and I am not complaining, but it gets too much.”

Last dance?

Especially when things are not going well. It is hard to talk about Zidane and not to talk of him as an artist, all graceful touches, like a ballet dancer. It is not a definition he shares. “It’s uncomfortable because if I’m playing in a way that is elegant, great. It’s nice that they say that. But I am first of all a footballer and I hope people enjoy me as a footballer on the pitch: a competitor, not a dancer. I am there to win. I was a player that always wanted to win,” he says. And by the time he left, Madrid had stopped winning.

Zidane’s final game had nothing riding on it. It was not the first time. In April 2003, FFT got to the heart of the club, the mechanisms, and the culture and explained that the galácticos project was unsustainable: it reinforced division and undermined some of the unwritten rules of the game. “Some privately fear that the club could end up imploding,” we wrote. Others did not see it, or chose not to. There were problems in paradise but they carried on regardless.

That season finished with the league title, but then it started to go wrong. In 2005, a Ronaldinho-inspired Barcelona defeated them 3-0 at the Bernabeu. “That was my worst match,” Roberto Carlos says, “when Ronaldinho thrashed us. He scored twice and I played really badly. It was also one of the first times that Lionel Messi really shone for Barcelona.”

One Madrid director had reportedly commented that they did not sign the Brazilian because he was so ugly that he would sink them as a brand, choosing Beckham instead. Barcelona did sign the Brazilian and won the European Cup, plus two leagues in a row. Before that, Valencia took the title. Madrid went empty-handed: after 2003, Madrid suffered a three-year drought, their longest spell without a trophy in over half a century.

Zidane blows out his cheeks. “Muchísimo tiempo,” he says. A very long time. Too long.

“And that,” he continues. “Is one of the reasons I left it. I might have been there longer if they had won more. But you say to yourself: ‘I’m an important player in this team and it’s three years ...’

Did you feel responsible? “Yes. In my last press conference, I said that: I am responsible for that. I am important here and I don’t like it. I retired in part because of that.”

Class system

What had been billed as the team that couldn’t lose had become the team that couldn’t win, slipping back in the Champions League, round by round, and in 2005 and 2006 not even getting close to competing for the league. In part that was because of the billing itself, the very nature of the project. The ‘galáctico’ title – which still wasn’t common currency in April 2003 – was a double-edge sword, a celebration of some of the best players in the world, the most impossibly glamorous team ever – but also the formalisation of inequality and the pressure that galactic status brings with it.

Many players saw the term “galáctico” as a weapon to be used against them. When galáctico is mentioned, Figo is quick to interrupt. “Aquí, nadie es galáctico,” he says. No one is a galáctico here. He continues: “When you win it’s fine, but when you lose it does you damage. There are jokes, comparisons, etc, and it’s always negative. That was a nickname constructed to sell, and that’s it.” Roberto Carlos also rejects the tag: “None of us felt like galácticos.” And Ronaldo agrees: “There was a negative tone to the word galáctico, a term we never chose to describe ourselves. We knew that there was already pressure at Real Madrid but over time that label heaped even more pressure onto us.”

“I think no one felt like a galáctico or above the rest,” Figo insists. Only they did or they were made to feel that way – and not just by the media: ‘galáctico’ was a term embraced and promoted by the club. Those who were not galácticos were keenly aware of the institutionalisation of ‘classes’ in the dressing room. Some complained that it was as if the stars were the only people at the club; they were its image and it was all about image. Other simply felt marginalised; that had effect on transfer policy and, despite the fact that it was a group of players who for the most part genuinely got on well, the dressing room. Asked why things started to go wrong, Zidane says: “I don’t know.”

“Maybe,” he offers, “there was too much respect among the players. When there were things that are not going well, you have to say so. And we didn’t do that. I don’t know why. Respect, maybe. Maybe because each person had a certain status ‘I can’t say this to them...’”

Classes, in other words? “Maybe, but above all because we seemed scared to say anything to the other player. If you have a problem you have to say so, you have to resolve that problem... as we didn’t.”

An example: one Madrid player was too afraid to take a shirt in to be signed by his own team-mates for a family friend, insisting: “I can’t go in there and ask Zidane or Ronaldo to sign this.”

Zidanes y Pavones

Madrid’s policy was defined as “Zidanes and Pavones”: Perez aspired to a team made up of the world’s best players, the Zidanes, and youth teamers like Paco Pavón. It was sold as an emotional concept: excitement and commitment, the best and the home-grown. But it was also a financial imperative: Madrid could pay a galáctico’s wage – at the time, around €6m – by offsetting tiny salaries for youth team players, some of them on as little as €150,000 a year. “A pittance,” as one irritated team-mate put it.

It also tended, as Santi Solari noted at the time, to the eclipse of the “middle class”. Players like Claude Makelele, who was vital in the side. Makelele was on a salary of under €1m a year, a sixth of his more illustrious team-mates. And he knew it – not least because he knew of their value as marketing tools. And because Madrid, at boardroom level, were not really bothered if he walked. Perez publicly insisted that Makelele was not good in the air and couldn’t play a pass.

When Madrid signed Nicolas Anelka for €25m, the then-president Lorenzo Sanz described it as a “beautiful madness”. Perez claimed that his big-money signings were not madness at all: they actually generated money for the club. But in order to do so, their image had to be exploited, with adverts and tours and presentations. They had to be marketable. Others did not have that image, which came to feel even more significant than what they actually did on the pitch.

In the summer of 2003, Real Madrid signed David Beckham. A few months before, FFT had suggested him as a potential new signing to Roberto Carlos. “But where,” the Brazilian asked, “is he going to play?” It was a pertinent question.

End of the cycle

At the same time, Vicente del Bosque was released as coach. Over the next two-and-a-half years Perez hired five coaches: Carlos Queiroz, Jose Antonio Camacho, Mariano Garcia Remon and Vanderlei Luxemburgo. None of them won anything.

He went through four sporting directors and over €440m worth of players in three years; 19 players in and 31 out. That summer of 2003, the exodus started: like Del Bosque, Fernando Hierro was released. Claude Makelele, Albert Celades, Steve McManaman, Fernando Morientes all departed too. Only Beckham came in. Here, at last, was pure galaticisim – and it didn’t work. The squad was painfully thin, especially at the back. “A Ferrari can’t run without tyres,” Queiroz complained.

So could the players see the shift coming, before the defeats even began? “Yes, yes, yes,” concedes Figo. When? “The fourth year, maybe. When we started to divert a bit, when we started to break the rules a bit of what a football team should be.”

Beckham’s signing had come to symbolise the shift but his team-mates are quick to defend him. “I’ve always had unfair things that were said to me,” Beckham insists. One of them came to be an obsession: the accusation that he had only come to sell shirts. The problem was that, however committed Beckham was, that was partly true.

“People said ‘Beckham: image’, but he was very, very professional, very serious,” Zidane says. “He always came to training early and worked very hard.” Figo adds: “David is phenomenal lad, a great person: he never created any problems. The image he is different to what he is like as a person and player. He’s an excellent professional.”

But? “It’s not his fault at all that they signed him with this aim or that one... I had a great relationship with him. I liked him a lot. He was an excellent player and I enjoyed working with him but the institutional part the club has to answer: why they signed him, what functions did they have in mind? What I can say about David is that he was great, excellent, likeable, and a friend. That matters most to me.”

Roll up, roll up

“[That summer] we went right round the world, from Los Angeles to China,” Figo recalls. “There were moments on that tour,” Zidane continues, “that I was thinking: ‘I’m not training, I’m always travelling, there are no training sessions, no rest. Thailand, China, Japan... I felt that maybe we didn’t train enough to prepare for the season. I felt more or less the same [as Luis] but it was the club’s policy and we had to respect that because we earned a lot of money and the club had to raise money from somewhere.

“You start to see things,” Figo continues. “You see people from outside in the dressing room. It’s a bit complicated. You lose the seriousness a bit. For example: one of those digressions was that we had an actor on the team bench and people filming us in the dressing room. My opinion is that... I don’t know... my opinion is that it’s not the right thing to do. But in the end, that’s what was done.”

“My opinion, and it is a personal opinion, is that it’s very important that the clubs seek income in publicity and so on ... but there has to be a balance. There was a moment in my personal opinion – and I’m sure others will disagree – that the balance didn’t exist. One thing is the rules of a football team; another thing the interest of marketing. There has to be a balance so that they don’t clash, to ensure that it doesn’t seem like publicity circus.

“I think we reached a point where we departed from the pathway that a football team should take. And I think we paid for that in footballing teams. The last two years that I was at Madrid ... we may have been benefited in marketing terms but I think in footballing terms we paid for it.”

But what fun it had been. In the end, they were victims of their own success; a success that was founded as much on their aura as their actual awards. They ended up being too big even for themselves. But they had been huge – and how they had enjoyed it. “Those first two years were incredible,” Ronaldo recalls. “I scored the first time I touched a ball for Madrid. I came onto the pitch for my debut and a few seconds later I scored. Then I scored again. I thought: ‘Wow, this is going to be great’.”

It was. From the goal after 14 seconds in the Madrid derby, to the hat-trick at Old Trafford: “I had never had a standing ovation at an away game before,” Ronaldo beams. From the Figo’s dribbles on one wing to Roberto Carlos, a bullet on the other. From Raul scooping the ball over countless keepers to David Beckham finding Zidane on the volley from so far away that one newspaper claimed the pass had been delivered from out on Orense Street – a mile away. From that volley to that volley, voted the greatest goal in Madrid’s history. From one Ballon d’Or to another to another. And always the promise of something else, a little hint of something special in the air. Something unexpected.

Luis Figo looks at the magazine again. He picks it up and takes it with him. A memento, a reminder. Good memories. The sun is streaming in through the glass windows onto the balcony. Sum it up in a word, Luis. “A privilege.”

This feature originally appeared in the June 2013 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!

Join The Club

Join The Club