Why Leeds United will always deserve more credit for their 1991/92 title win

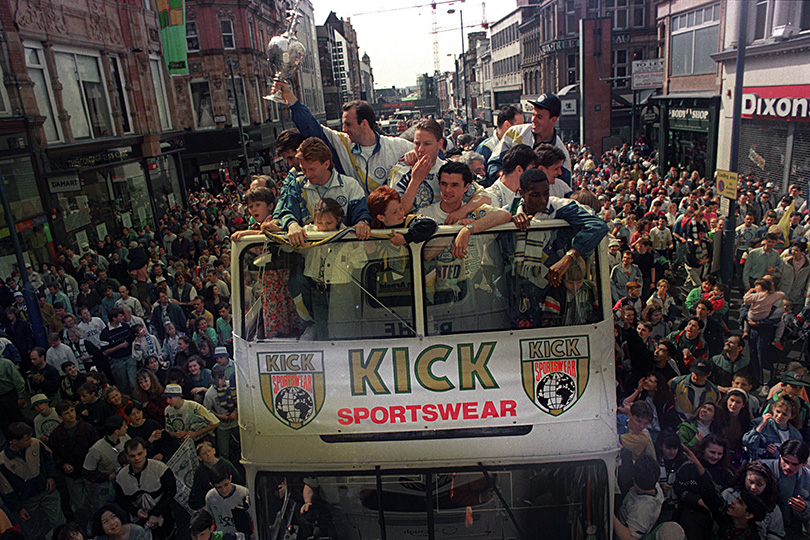

25 years ago, in the final season before England’s top-tier became the newfangled Premiership, an unlikely Whites side snatched the championship from Manchester United

Viewed a quarter of a century on, 1991/92 was one of English football’s strangest years. Nobody knew it, but as Kenny Dalglish departed, Liverpool’s lengthy dynasty had come to an end. Likewise, few could have predicted the remarkable Fergie reign that was about to emerge in its place.

It was the season finale of the dusty old Division One. The bells, whistles, pyrotechnics and vast sackfuls of cash of the Premiership (later Premier League) were approaching – and nobody knew quite what to expect.

As a result, Leeds United’s utterly remarkable 1991/92 league win is often mis-remembered. Those hazy of memory recall a vaguely agricultural side, overseen by a glum-faced Howard Wilkinson, still not quite free from the whiff of ‘Dirty Leeds’, occasionally enhanced by Eric Cantona’s cameos like pearls before swine.

This representation is deeply unfair. The last title triumph by an English manager in the last season before the crucial abolition of the boring, boring back-pass rule may have come just before a major footballing 1066 (the foreign hordes were coming to fire an arrow into the eyeballs of our meat ’n’ potatoes, 10-pints-after-the-match “professionals”) – but it was a tactical masterpiece.

It was also a huge shock. Leeds, who’d been a very average Division Two side just two seasons earlier, were the most surprising title winners since Nottingham Forest in 1978. It’s not stretching things too much to compare their rollercoaster win with Leicester City’s miracle of 2016.

Howard lifts the curse

Wilkinson was the catalyst. He arrived from First Division Sheffield Wednesday at second-tier Leeds in autumn 1988. The club, cursed by the shadow of Don Revie, were in the bottom half of the table and seriously demoralised.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Leeds United’s utterly remarkable 1991/92 league win is often mis-remembered

Wilkinson had in mind a 10-year plan. He would focus on serious youth development, to mirror what was going on at Manchester United. Hopefully this would culminate in Leeds being restored to their 1970s pinnacle and winning the league.

First, though, there was some serious training ground drilling to endure. A deeply average squad was worked mercilessly (hence the ‘Sergeant Wilko’ nickname, a play on the classic American comedy Sergeant Bilko – ask your dad).

It had an effect almost immediately. The club rallied to 10th in 1988/89, and some key individuals were put in place. Academy products Gary Speed and David Batty stepped up, while defender Chris Fairclough was signed from Spurs.

Fergie vs Strachan

Most importantly, a 31 year-old Gordon Strachan – who’d fallen from favour with Alex Ferguson at Manchester United – was persuaded to repel a huge offer from Ron Atkinson’s Sheffield Wednesday in March 1989 and drop down a division.

“People thought he was coming here to retire... No."

“People thought he was coming here to retire,” claimed his fellow Scot Gary McAllister in the new documentary about their title victory, Do You Want To Win?, before pointedly adding: “No.”

Strachan, immediately handed the captain’s armband, was on a one-man crusade to prove Fergie wrong. He was the side’s hub as they cruised to the Division Two title in 1989/90, and secured fourth place in Division One the year after, with Strachan winning the FWA Player of the Year award in the process.

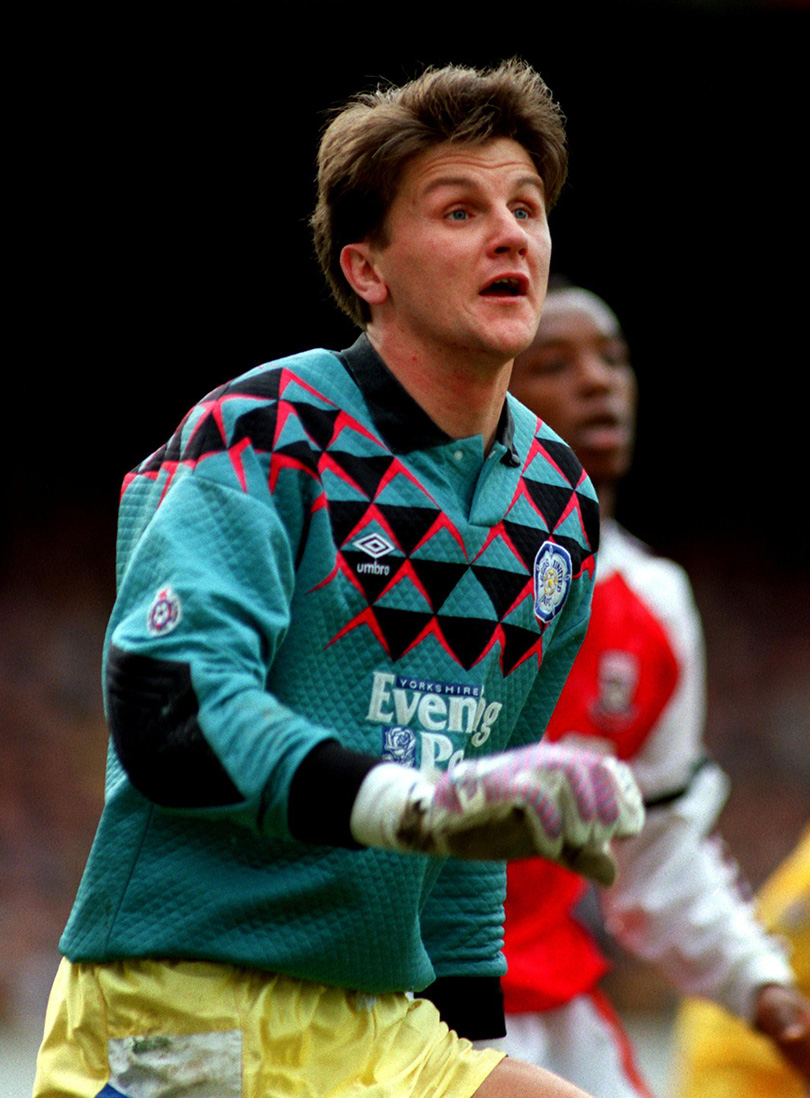

“You’ve got your vision, you’ve got your messages, you want people who mirror those beliefs and that culture,” says Wilkinson in Do You Want To Win? With Arsenal goalkeeper John Lukic also joining the ranks, he suddenly had just that.

It was a decent first XI, without doubt, but no pundits predicted a title push for 1991/92. Leeds’ back four – Fairclough, Mel Sterland, Chris Whyte, Tony Dorigo – contained no real star (although Dorigo’s ease on the ball was impressive). Yet they did a quiet, solid job all term; only Manchester United and Villa would concede fewer.

Ludic’s extraordinary shot-stopping exploits often saved their bacon: a remarkable performance at Anfield, on the way to a crucial 0-0 during the run-in, stands out.

Midfield marvels

It was the Whites midfield that really shone, however, brimming with vigour and vision but always ready for war. With two Scots, a nonsense-free Yorkshireman and a Welsh wing wizard, this could have been a great Shankly or Paisley midfield from the 70s – or indeed a wonderful Alex Ferguson unit from the later '90s.

Batty was the gruff Yorkshireman’s gruff Yorkshireman, a wrecking ball who could also play a bit

Speed in his younger incarnation was a jinking handful; not quite in the Giggs mould, but a horrible afternoon’s work for any right-back nonetheless. Batty was the gruff Yorkshireman’s gruff Yorkshireman, a wrecking ball who could also play a bit. McAllister was a Rolls-Royce, adding calm and keeping possession when things got too frenetic. Strachan provided the drive and leadership.

Up front was the archetypal big man-little man combo: Lee Chapman and Rod Wallace. Chapman was devoid of pace but a genius in the air, and utterly fearless – 6ft 3in and unafraid to ram his bonce where it hurt.

He was one of the few players who could genuinely shake up Manchester United’s Steve Bruce and Gary Pallister, and he scored vital goals all season long – 16 of them, including key hits against Manchester United, Wednesday and Arsenal. Sterling’s passes in particular seemed to be laser-guided to Chappy’s forehead.

Wallace, meanwhile, added cool, classy finishes, while England international Steve Hodge and much-loved Yorkshire workhorse Carl ‘Shutty’ Shutt also chipped in with vital strikes.

No pressure, lads

Pressure, however, was also a vital factor. Importantly, Leeds didn’t feel much. They were still new to the top flight, and while the start of the season showed their potential – thrashings of Manchester City and Southampton, a 1-0 win over Liverpool, no losses until October – Leeds were still not really being spoken about as possible champions.

Wilkinson was playing the game perfectly, on and off the pitch

“We were all fairly pleased just to be doing so well,” remembers Batty. “Not until the end, when the Man U boys slipped, did we think anything other than it was nice to be there or thereabouts.”

Wilkinson was playing the game perfectly, on and off the pitch. At Villa Park, he deployed John McClellan cleverly in defensive midfield – an early version of the Makelele role – masterminding a wonderful 4-1 victory.

He was always forward-thinking: a sports science enthusiast, he recognised the value of nutrition and tweaked pre-match meals accordingly, years before Arsene Wenger was given credit for doing something similar.

A face that would make you cry across a poker table also disguised a Sahara-dry sense of humour - and surprising sophistication: he spoke to Eric Cantona, then still a fringe player, in French.

As the season wore on, and Leeds found themselves steadily gaining points and staying in the hunt, Wilko’s perceived dourness also proved a real asset.

Alex Ferguson might have become legendary for his mind games over the next two decades, but that year, he was truly outwitted

Alex Ferguson might have become legendary for his mind games over the next two decades, but that year he was truly outwitted – and no doubt learned a lot (about what to say, and what not to say, when it comes to a title battle).

As Leeds became more and more of a threat, and went top, Ferguson would insist that the pressure was on his rivals, because they’d not won anything before. But the more vocal the Manchester United boss became, the less Wilkinson said. There was a feeling of serenity around Elland Road as their opponent imploded.

Do you want to have a nice time?

Leeds got the job done. Batty remembers it in typically straightforward terms. “We played the football we needed to: basic, hard-working and direct,” he says. “McAllister, Speed and Chapman could finish.” Wilkinson, meanwhile, used the press criticism of his side’s style as a motivational tool. “Do you want to win this game, or do you want to have a nice time?” he asked. They wanted to win.

Yes, they were ‘hard’ – but rarely truly dirty

But even the protagonists themselves were being a little unfair on what could be a genuinely electric side on their day. Yes, they scored a lot from set-pieces and crosses. Yes, they were ‘hard’ – but rarely truly dirty. Watch them again as they dismantle a very good Sheffield Wednesday side 6-1: this was a team that could play.

Most of all, they had character. After a 4-1 crushing by QPR, Leeds hit straight back with a 5-1 win over Wimbledon. When Manchester City threatened to do their hated metropolis mates a favour by hammering Leeds 4-0, the Yorkshire outfit responded with a 3-0 win against Chelsea.

It was here that Cantona – a truly risky £900,000 Wilkinson signing from Nimes – chipped in.

His importance to the title triumph has perhaps been overstated, given that he started just six games that year. But while Ferguson’s side laboured to get over the line, incredibly burdened by the weight of history, the Frenchman sprinkled a little bit of stardust around Elland Road, adding to their sense of relaxation, scoring three goals, and providing a number of fine assists for Chapman. They’d gain 13 points from their last five matches.

The title was finally teed up thanks to a glorious, barmy, windy and fluke-ridden match between Sheffield United and Leeds, full of near-comedic moments. The Blades’ Alan Cork opened the scoring thanks to some Keystone Cops Leeds defending. Wallace equalised in a barmy goalmouth scramble.

A bizarre, windswept cross from McAllister was nodded in by Jon Newsome to make it 2-1, before a Lee Chapman deflected own goal levelled matters again. Finally, aptly, marvellously, a mis-timed header back to his own goalkeeper from Brian Gayle gave Leeds the 3-2 win.

United lost, painfully, to Liverpool the next day, sending the League trophy to Elland Road. A bemused Wilkinson was doorstepped for comment midway through his Sunday lunch.

He seemed a little lost for words. And if he’d known the future, he’d have been more dumfounded still. Hard times lay ahead for Leeds, and for Wilkinson himself. Neither would reach this apex again. It would be the last time a side assembled in such a way – many players over 30, plenty from the lower leagues – would conjure such a win. Until 2016, at least.

For that, Wilkinson’s Leeds deserve not to be forgotten. They were far more than just a footnote, sandwiched between modern football and more innocent days.

Now read...

Nick Moore is a freelance journalist based on the Isle of Skye, Scotland. He wrote his first FourFourTwo feature in 2001 about Gerard Houllier's cup-treble-winning Liverpool side, and has continued to ink his witty words for the mag ever since. Nick has produced FFT's 'Ask A Silly Question' interview for 16 years, once getting Peter Crouch to confess that he dreams about being a dwarf.

Join The Club

Join The Club