Kevin Keegan: how Liverpool, Hamburg, Southampton and Newcastle fell Head Over Heels In Love with King Kev

Fifty years ago, a 20-year-old Kevin Keegan made his Liverpool debut following an almighty leap from the Fourth Division. King Kev's incredible success extended far beyond the Kop, however, during a fascinating career of pop single, punch ups bike crashes... and cracking perms

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

FourFourTwo Daily

Fantastic football content straight to your inbox! From the latest transfer news, quizzes, videos, features and interviews with the biggest names in the game, plus lots more.

Once a week

...And it’s LIVE!

Sign up to our FREE live football newsletter, tracking all of the biggest games available to watch on the device of your choice. Never miss a kick-off!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

This feature on Kevin Keegan first appeared in the September 2021 issue of FourFourTwo.

Subscribe to FourFourTwo today and save! You'll get 13 issues per year...

It all started in the back of a van, rumbling between Doncaster and Scunthorpe.

It was the summer of 1966 and sat behind the wheel was Bob Nellis, a furniture salesman who’d once had trials with Rovers. Now in his thirties, Nellis’ football career consisted of the odd Sunday League kickabout as well as helping to coach a local kids team.

Dreams of scoring a Wembley winner had long since expired; Nellis didn’t even have enough balls or kit to run his training sessions. Yet as luck would have it, the solution to acquiring some was getting changed on the back seat of his van: a scrawny 15-year-old lad named Joseph.

Nellis initially met the youngster a few weeks earlier, and hadn’t much enjoyed the encounter. Turning out for his local pub team, he was tasked with marking the skinny waif playing on the right of midfield. Such was the runaround Nellis received, he approached the kid at the final whistle. Nellis had a contact at Scunthorpe United, he explained, and 10 balls and a bag of kit had been promised if he could bring them someone worth signing.

Joseph had been to trials before, including at Coventry, but his miniature 5ft 8in stature proved a stumbling block. Still, the offer was a no-brainer for this pint-sized pub footballer who’d just quit school to work for a nearby brassworks firm.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

Once delivered to the Old Show Ground, Scunthorpe’s original home, the prodigy’s trial consisted of a cross country run before a match on the car park adjacent to the pitch. Even on gravel, it was obvious that the teen was wasted on ballcocks and toilet fittings. Iron manager Ron Ashman summoned the trialist to his office before the session had even concluded.

That night, Nellis drove home with a new bag of balls on his back seat. And Joseph Kevin Keegan was a professional footballer.

We need to talk about Kevin

Scunthorpe had been relegated to the Fourth Division before Keegan made his first-team debut in September 1968, aged only 17. The team trained on a rugby pitch owned by the local council, and players took turns to drive the minibus to matches. During the summer, they found part-time work to beef up their income; Keegan, for example, worked on the railways for British Steel.

Despite his shabby surroundings, the young forward was determined to shine. “The thing that impresses me most about you is that you’re a hundred percenter,” fitness trainer Jack Brownsword told him. Keegan would regularly be seen running up and down the terraces, weights tied to his waist, long after team-mates clocked off.

The starlet made 89 appearances across his first two seasons, and his performances quickly attracted interest from bigger clubs. Indeed, such was the buzz around Keegan that Granada Television visited Scunthorpe’s Quibell Park training ground to interview the coveted 19-year-old.

“I’m ’appy here... it’s a very good club,” the pearly-faced Keegan tells presenter Gerald Sinstadt in his soft Yorkshire accent, while mud-caked team-mates shoot into a rugby goal over his shoulder. “I’m getting first-team football – should think if I went First Division, I’d struggle a bit.”

It was soon time to test that hypothesis. In 1971, Scunthorpe accepted a £33,000 offer from Liverpool. Ashman, who negotiated the deal himself, drove Keegan to Anfield. “Have you got a good suit?” he asked his protégé. “Where you’re heading, you’re going to need to look smart.”

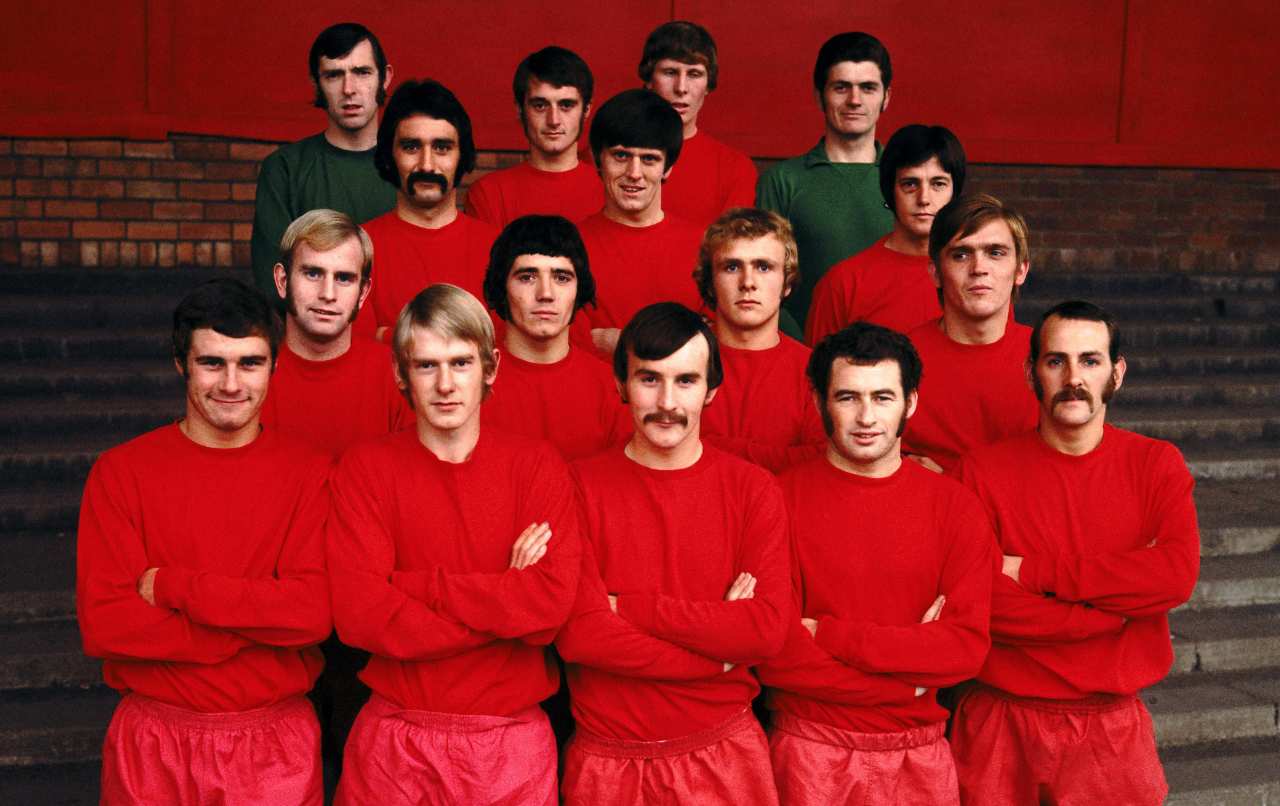

The Reds had gone five campaigns without a major trophy, and bringing in a 20-year-old from the fourth tier went unnoticed.

“We didn’t know anything about him,” Ian Callaghan, Liverpool’s record appearance holder with 857 outings between 1960 and 1978, tells FFT. “We went on a pre-season tour and this lad called Kevin came with us. That was the first time we’d ever seen or heard of him.”

Yet Callaghan admits the squad were instantly impressed by Keegan’s determination. “His enthusiasm and energy were fantastic from the off,” he recalls. “He was a very fit young guy and he gave everything – you could see how much he wanted it.”

Though he was signed as an understudy to Callaghan at right-midfield, Keegan’s lack of positional discipline during training prompted a rethink. After watching him play upfront in a youth match, Reds boss Bill Shankly gave him a chance there in a first-team training game. Unbridled by defensive responsibilities, Keegan scored four in a 7-0 rout.

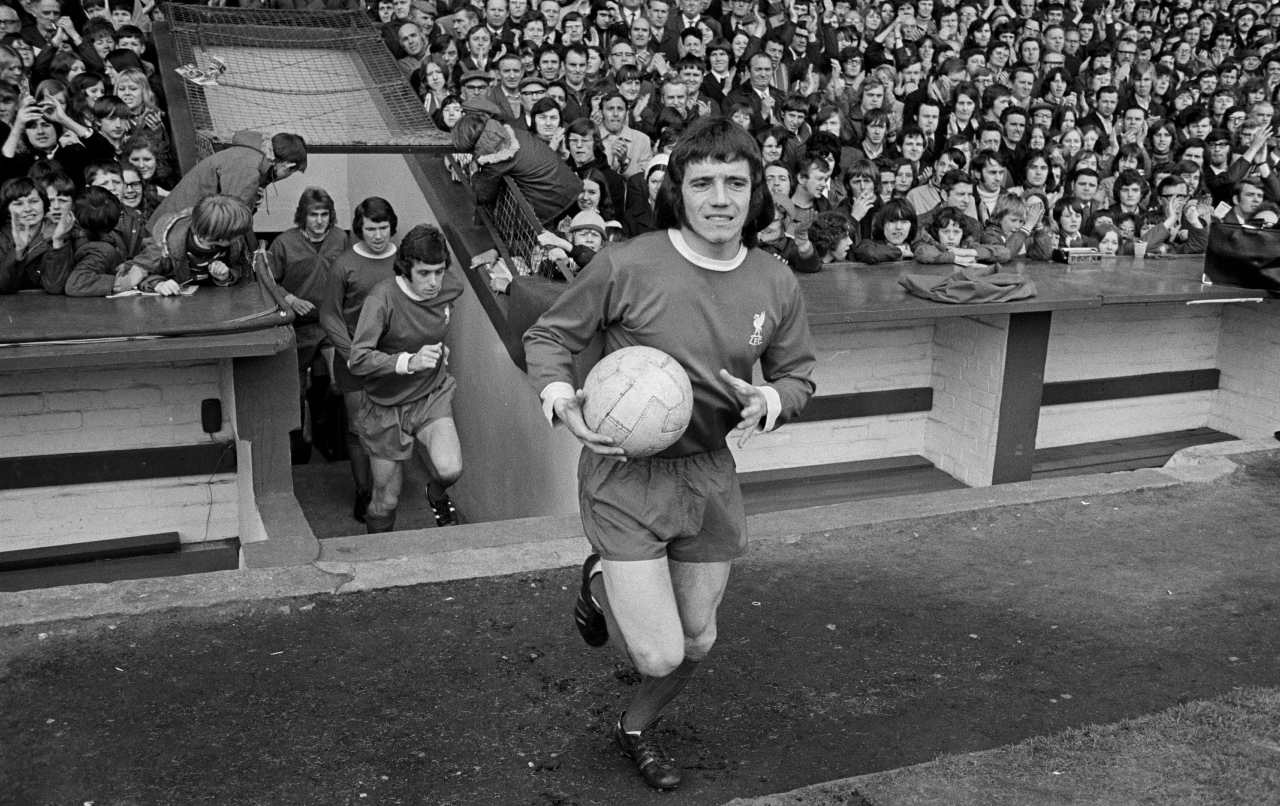

A senior debut soon followed, with Keegan handed the No.7 shirt against Nottingham Forest at Anfield in August 1971. He arrived into the dressing room almost half an hour late – “I hadn’t anticipated the traffic around the ground on matchdays” – but shook off a Shankly rollicking to score the opener after 12 minutes in a 3-1 victory. Unsurprisingly, Keegan was teed up that day by Welsh strike partner John Toshack.

“He quickly formed an excellent partnership with Tosh,” remembers Callaghan. “They had such a connection.” In fact, so in tune did the pair seem, they later appeared on a 1974 ITV show to try to prove if they actually had telepathic powers. “It came back negative,” confessed Keegan, “but rather than spoiling everyone’s fun, we kept that quiet.”

Keegan made another 41 appearances during his debut campaign, scoring 11 goals in all competitions. Liverpool went potless for a sixth year running, but that all changed in 1972/73 when both Keegan and Toshack plundered 13 league goals apiece, helping Liverpool to a first title since 1965/66. Weeks later, they followed it up with a 3-2 aggregate triumph over Borussia Monchengladbach in the UEFA Cup final; Shankly’s paltry purchase from Scunthorpe bagged a brace against the Germans in a 3-0 first-leg romp.

By the 1973/74 season, Keegan was the Merseysiders’ big game player. After losing the league title to Leeds, he scored twice in the FA Cup final win over Newcastle – leading to an infamous Charity Shield scuffle with Billy Bremner. Keegan and the Scot received three- and eight-match bans respectively.

Little could King Kev lower in his gaffer’s estimations, however. “Shankly loved Kevin like a son,” smiles Callaghan. “They adored each other. Bill made everybody feel special. He didn’t like to play favourites with players, but their bond was clear.”

By the mid-70s, Keegan’s adulation had reached Beatles-level. The frontman was the driving force in Liverpool’s second wave of dominance under Shankly, then improved further under the Scot’s successor Bob Paisley. He was named the Football Writers’ Association’s Player of the Year in 1976 after the Reds’ second league and UEFA Cup double in just four campaigns. Kev-mania was in full swing.

“Kevin came to Liverpool and developed into one of the best players – and one of the most famous men – in the country,” says Callaghan. “He became the next superstar after George Best. You’d go out to the car park after the game and there’d be queues of fans waiting to see him, and he wouldn’t head off until he’d signed every last autograph.”

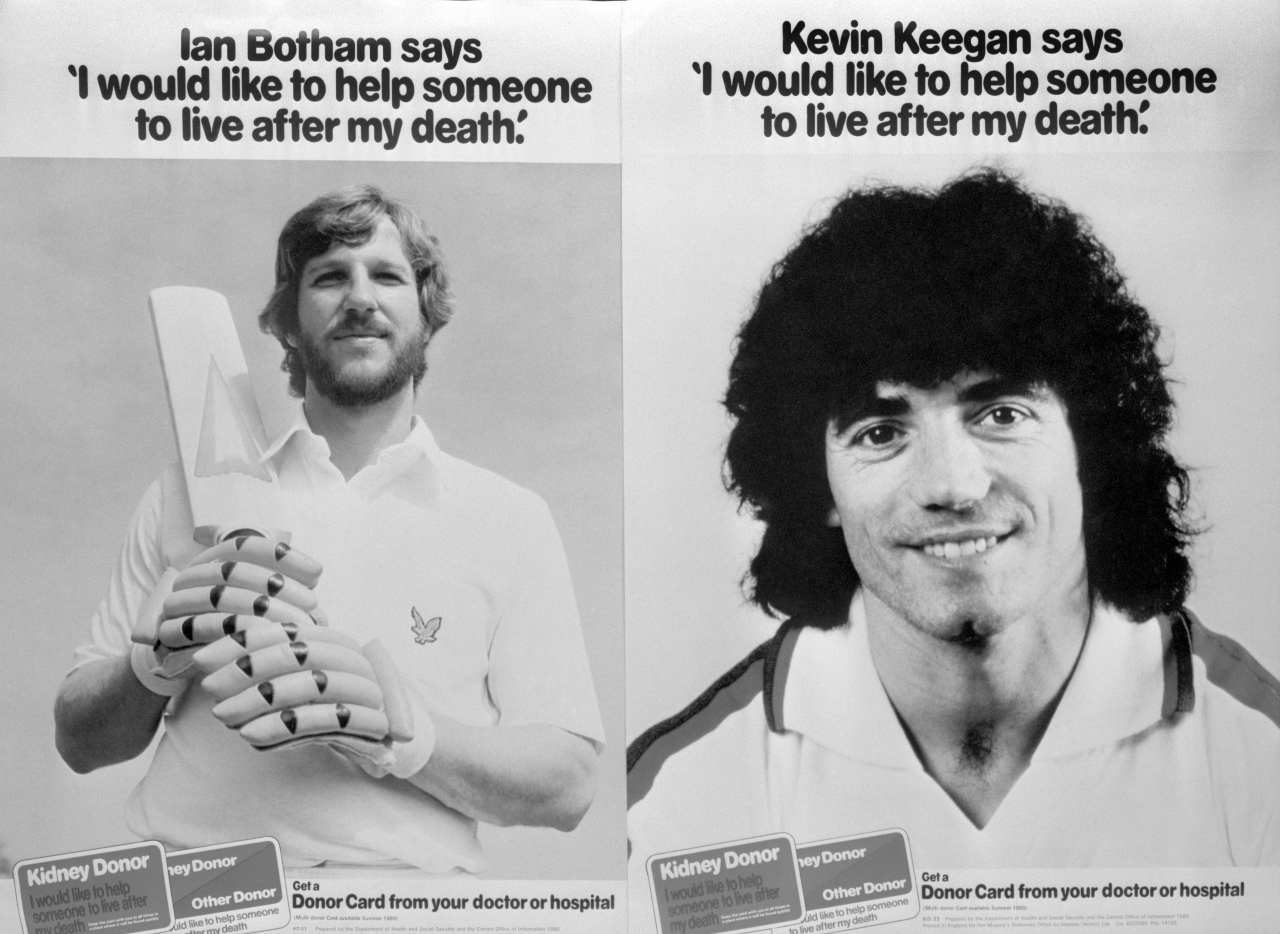

Keegan was one of the first footballers to recognise his marketability. He opened shops and starred in advertisements, including for Brut aftershave with ex-boxer Henry Cooper.

In the summer of 1976, he appeared on ITV’s Superstars. The show pitted athletes from a range of sports against one another in Olympic-style events, with Keegan hurtling off a bike and grazing his shoulder.

“The people in the stands have come here to see me make a fool of myself and they’ve got a right to it!” he insisted, before dusting himself down to win the steeplechase and claim overall victory.

“It would never be allowed now,” chuckles Callaghan. “But it was great entertainment.”

Keegan had also become key for England after making his debut against Wales in 1972. The ’70s was a fallow period for the national team, however, as the Three Lions failed to qualify for either the World Cups in ’74 and ’78, or Euros in ’72 and ’76.

“Everyone was disappointed with the way things went,” his England team-mate Mick Channon tells FFT. “People analyse why we didn’t get to any tournaments, but ultimately we weren’t f**king good enough.”

The blow of missing out on Euro 76 would be softened by extra success at club level. A dozen goals helped to deliver the 1976/77 championship, before Monchengladbach – regular Reds victims back then – were beaten 3-1 in Rome’s European Cup final.

“Kevin was the man of the match,” grins Callaghan. “He ran legendary Gladbach defender Bertie Vogts, his man marker, ragged that night.”

Ten years after that trip in the back of Bob Nellis’ van, Keegan had reached the pinnacle. But despite the relentless glory at Anfield, he was getting itchy feet.

“He admitted to us at the beginning of the European Cup-winning campaign that he was seeking a new challenge,” reveals Callaghan.

“Kevin rarely changed his mind, and made arrangements to leave us before the season’s end. The way he played in that European Cup final was the perfect send-off.”

Perms and pop singles

If Keegan’s decision to leave the European champions at the height of his powers raised eyebrows – “I’m not being vindictive,” said Paisley, being vindictive, “but I wouldn’t play a man for England that goes abroad” – his destination was even more bewildering. The 26-year-old didn’t join another English club or European giant like Bayern Munich or Real Madrid. Instead he opted for Hamburg, who’d just finished sixth in the Bundesliga.

“We were all surprised Kevin came to HSV,” chuckles right-back Manfred Kaltz, who made 729 appearances for them between 1971 and 1991. “It was a big transfer for the club – he’d just won the European Cup, so was a name on everybody’s lips.”

The size of the deal added to the surprise: £500,000 was a British transfer record, and more than doubled Germany’s. Just as the Beatles swapped the Mersey for the fortunes on offer by the Elbe in their early career, Keegan knew his worth.

“With God and Kevin Keegan with us, we will win,” bragged Hamburg general manager Peter Krohn at the attacker’s unveiling.

The sums rubbed Keegan’s team-mates up badly, though. A group led by captain Peter Nogly knocked on HSV boss Rudi Gutendorf’s door to share their reservations. “If you put the little English guy in, we don’t want to work with you,” they reportedly warned. “We don’t need him and we don’t like him.”

Meanwhile, the England international struggled to settle in northern Germany. He didn’t know the language – admitting in one instance to visiting a hardware shop to buy a fuse, then leaving with Christmas lights just to end the embarrassment for everyone – and began to suspect that his colleagues were intentionally not passing the ball to him.

Keegan told his wife that he felt “unusually vulnerable”, but Kaltz believes he was being sensitive. “No one tried to send him back to England or anything,” he tells FFT. “He just had a hard time with the language. Everyone knew that Kevin would earn a lot of money, but I doubt anyone was envious of him for it.”

Either way, emotions swiftly began to get the better of Keegan. During a winter friendly against VfB Lubeck on New Year’s Day 1978, the Englishman snapped. Unhappy at the repeated roughhousing from an opposition defender, Keegan “knocked his lights out” before walking straight off the pitch.

An eight-week ban proved a turning point. Keegan got a call from an old pal. “Did you hit him properly, son?” Shankly cackled down the line. “Was it a left or a right hook? Did he stay down until the count of 10?” Keegan promised his former manager that he’d make a go of his career in the Bundesliga.

The first step was trying to master the language. “He put in a lot of effort and learned German very quickly,” recalls Kaltz. “He needed a bit of time to settle, but soon fitted in extremely well. In terms of commitment, attitude and ambition, everyone acknowledged that Kevin really was something special.”

It didn’t hurt that Hamburg’s early-season promise crashed in Keegan’s absence – they won only two of the eight games he missed. Eventually, his team-mates began inviting him out and requested updates about when he could play again.

With the barriers now down, Keegan was touched to turn up for training one day and find full-back Peter Hidien sporting a perm. Keegan had pioneered the haircut to mixed early results. On first viewing, wife Jean burst out laughing, while Keegan’s agent jokingly tried to disown him in public. Soon though, it was the footballer barnet du jour.

“I even tried it myself, but it was a complete disaster!” laughs Kaltz.

At the end of Keegan’s debut campaign, in which Hamburg finished 10th, Branko Zebec was appointed as manager. His impact was profound. A fierce disciplinarian, the Yugoslav believed his new squad needed toughening up, as punishing fitness sessions twice a day became the norm. “I’d never trained so hard in my life,” groaned Keegan.

But there was method to Zebec’s madness. Hamburg outran and outmuscled opponents to reach second place in the Bundesliga at Christmas, as Keegan – who hit a hat-trick against Arminia Bielefeld in HSV’s last game before the turkeys came out – won his first Ballon d’Or in 1978. Die Rothosen went 13 matches unbeaten from March to a final-day defeat by Bayern Munich and cruised to the title, Keegan smashing 11 goals. Supporters affectionately dubbed him ‘Mighty Mouse’ due to his powerful yet diminutive frame, and Kaltz concedes the team became reliant on Keegan’s ability to win.

“You could play him in midfield or up top,” he explains. “He was strong in the air, a good dribbler, lightning fast and a great scorer, but he also worked incredibly hard defensively.”

In true superstar form, Keegan celebrated Hamburg’s victory by releasing a pop single. Head Over Heels In Love was a chart success, selling more than 200,000 copies in Germany and peaking at No.31 in the British rankings. “I actually thought that song was quite good,” titters Mick Channon, who used to rib Keegan about his England team-mate’s pop ‘career’.

That Bundesliga crown would be Keegan’s only silverware in Germany, although he did win a second successive Ballon d’Or in 1979, before Hamburg lost the 1980 European Cup Final to Brian Clough’s Nottingham Forest in Madrid. By then, the headstrong Keegan had already revealed he was returning to England. Kaltz believes the intensity of Zebec’s training sessions were a major factor in his decision. “It meant we often lacked energy towards the end of matches,” he says. “If he’d stayed, I think we would have been champions two or three more times.”

Auf wiedersehen, Kev

It’s difficult to imagine any Ballon d’Or holder coming to the same conclusion as King Kev. He spurned offers from Real Madrid, Juventus and the USA to join Southampton: a Second Division outfit as recently as 1978, but who’d just come eighth in the top flight.

The move was all down to Saints manager Lawrie McMenemy, who called Keegan under the guise of needing some light fittings for his home. “They’re only made in Hamburg, Kevin,” he pleaded. “Could you bring a few back for me on your next visit?” Cunningly, McMenemy soon turned the conversation to Keegan’s plans once his Hamburg contract expired that summer.

“Lawrie was certainly a wheeler dealer,” smiles Channon, into his 15th Saints year by then. “He knew what was going on and who was available. But Kevin was Europe’s player of the year and probably the best footballer in the world. You don’t often get characters like him at Southampton.”

Keegan’s hopes of winning a league title with a struggling club didn’t pay off a second time. A talented-yet-ageing crop – including Channon, Charlie George and 1966 World Cup winner Alan Ball – did, however, help Saints to what was then their highest ever league finish of sixth in 1981, before ending seventh in Keegan’s second season.

His 26-goal haul in 1981-82 bagged him the First Division golden boot, as well as the PFA Player of the Year award. Saints may not have been top class, but in Channon’s eyes his strike partner still was.

“Kevin was in his prime when he arrived at Southampton,” he remembers. “He’d score goals, make goals and dictate games. If his name was on the team-sheet, you knew we were guaranteed another few thousand fans through the turnstiles.”

Ahead of the 1982/83 season, the recently retired England captain – who’d finally made a World Cup outing that summer, albeit for 27 injury-doomed minutes against Spain – made another shock move. For once, though, fans could understand the destination.

Keegan’s ancestors had emigrated from Ireland to Newcastle. His grandfather, Frank, was a local hero: a mine inspector who saved 30 lives following the West Stanley Colliery explosion in 1909. His father Joe and uncle Frank also spent their working lives down the pits; their Saturdays at St James’ Park. It was Keegan’s homecoming, even as the Magpies languished in the Second Division.

Tens of thousands mobbed the stadium for Keegan’s unveiling, and the queue for season tickets went around the block. Those frenzied scenes had nothing on Keegan’s debut: a 1-0 win over QPR which featured a goal from the man himself. The 32-year-old celebrated by launching himself into the swaying support.

“I could have stayed there forever,” he later reflected. The atmosphere Keegan inspired was only outshone by his brilliance.

“He was the messiah to those fans,” former Newcastle and Northern Ireland midfielder David McCreery tells FFT. “But 100 per cent, he was still a world-class player. The rest of us went onto the pitch knowing he was going to be the difference.”

For Keegan, mere adoration wasn’t enough. He felt it was on him to take the club back to the top flight, and was disappointed with the team’s fifth-place finish in his debut season. But Peter Beardsley’s arrival from Vancouver Whitecaps proved significant in year two – his work-rate and creativity allowed an ageing Keegan to prosper. By then 33, the messiah netted 27 goals in 41 appearances to steer Newcastle to promotion.

Leading the Magpies in the First Division, 13 years after his Liverpool bow, seemed the perfect end to a remarkable career. But King Kev had already chosen to retire.

“The players and the manager, Arthur Cox, tried to convince him to stay on,” continues McCreery. “We knew what a huge asset he would be in the First Division. But when Kevin makes his mind up, there’s no changing it.”

McCreery rates Keegan as “one of the best I played with, alongside George Best and Paul Gascoigne.” Kaltz calls him “a great player and a great person” – sentiments echoed by Channon. “Wherever Kevin went, he made a massive impression on everyone,” he says of his friend. “He was top dog.”

But Callaghan, like many Reds supporters, believes Keegan’s playing legacy belongs to Anfield. “He’s one of the greatest players in Liverpool history,” he declares. “Kevin was the best. It’s that simple.”

Keegan’s career may have been officially over in 1984, but for a man whose perm and pop career broke the mould for footballers, there was time for one more piece of pizzazz: a farewell friendly between Newcastle and Liverpool at a sun-kissed St James’ Park. Fans held up banners reading “Auf Wiedersehen, Kev”, as a teenage Alan Shearer watched in awe as ball boy.

“There were probably another 15,000 fans outside wanting to pay their tributes,” says McCreery, who played in the 2-2 draw. “Kevin had brought good times back to the club and people wanted to thank him.”

The most memorable moment came at the final whistle. A white helicopter landed on the centre circle as Keegan completed a closing lap of the pitch, a horde of supporters in tow. Then, wiping tears from his eyes, he climbed aboard his chariot.

A career which started in the back of a van ended in a helicopter. Up it went, high above the stadium. Its passenger took one last look at the swirling sea of black and white below, crossed the Newcastle skyline and vanished into the blue.

Subscribe to FourFourTwo today! Guarantee the finest football stories and interviews dropping on your doorstep first every month.

NOW READ

BETWEEN THE LINES Kevin Keegan on Newcastle's 1995/96 Premier League challenge: “I still have nightmares about how we threw the title away”

RETRO How the 1990s saved English football

QUIZ Can you name the all-time Premier League stats holders?

Ed is a staff writer at FourFourTwo, working across the magazine and website. A German speaker, he’s been working as a football reporter in Berlin since 2015, predominantly covering the Bundesliga and Germany's national team. Favourite FFT features include an exclusive interview with Jude Bellingham following the youngster’s move to Borussia Dortmund in 2020, a history of the Berlin Derby since the fall of the Wall and a celebration of Kevin Keegan’s playing career.

Join The Club

Join The Club