From hat-tricks to handbags to early doors: what are the origins of the strange language of football?

Football phrases roll off the tongue so naturally that we barely stop to think about how weird and wonderful some of them are. Where do these odd idioms come from? And can FFT really stake a claim to one?

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Five times a week

FourFourTwo Daily

Fantastic football content straight to your inbox! From the latest transfer news, quizzes, videos, features and interviews with the biggest names in the game, plus lots more.

Once a week

...And it’s LIVE!

Sign up to our FREE live football newsletter, tracking all of the biggest games available to watch on the device of your choice. Never miss a kick-off!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A small fish in football’s massive pond.

"Their superb cup run has banked more than £110,000 for the non-league minnows.” - The Guardian, 2005.

Over the moon

Football folk who aren’t sick as a parrot may well be over the moon. The phrase’s origins lie with the 18th-century nursery rhyme Hey Diddle Diddle, in which, of course, a cow jumps over the moon.

Its first use in football is credited to Alf Ramsey, who said, after managing Ipswich to the league title in 1962: “I feel like jumping over the moon.” Then in 1970, when Keith Weller was transferred from Millwall to Chelsea, he declared himself to be “over the moon about the move”.

Park the bus

This figurative definition for the defensive tactic of getting as many players behind the ball as possible was introduced to British football by Jose Mourinho during his first season at Chelsea in 2004.

After being held to a goalless draw by Spurs, the Special One told reporters: “As we say in Portugal, they brought the bus and they left the bus in front of the goal.” Ahead of the return match later that season, Mourinho said: “We bring the bus this time. We are going to try to win but maybe we need to park the bus.” The tactic worked – Chelsea won 2-0.

Scored a hat-trick

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

A team in a state of disorder and confusion. Derived from ancient dice game 'hazard', in which sixes and sevens were difficult scores.

“The Preston team, through injury and illness, was all sixes and sevens.” - The Daily Express, 1900.

In the 1860s, while association football was being invented, popular magician John Henry Anderson, ‘The Wizard of the North’, wowed theatre crowds with his “demon hat trick” – the original rabbit-from-a-top-hat illusion.

But the sporting origin of this idiom can actually be found in cricket. In 1858, after Heathfield Harman Stephenson took three wickets in consecutive balls for the All-England XI against Hallam in Sheffield, a collection was held to honour his feat, with the proceeds used to buy him a hat. The cricketing treble soon became known as a ‘hat-trick’ and, by the end of the Victorian era, the phrase had transferred across to football.

In 1899, The Yorkshire Herald described a match between York Wednesday and Malton Swifts in which a chap called Hough, having already scored two goals, “got the hat-trick by scoring number three”. In the early years, players “got the hat-trick”.

By the 1950s, they “scored a hat-trick”. In more recent years a further distinction has developed. In 2001, The Times reported that Norwich striker Mark Robins had scored “with head, right foot and left foot respectively to complete a ‘perfect’ hat-trick”.

Missed a sitter

Loss of footballing nerve. Derived from the Victorian phrase 'no bottle', meaning 'useless'.

“Nasri is paid £150,000-a-week, but he bottled it in the wall.” - The Daily Mail, 2012.

Another cricketing term, ‘missing a sitter’ originally meant dropping an easy catch. “A ‘sitter’ is a catch which falls absolutely into the hands,” explained Tit-Bits magazine in 1898.

Within a few years it was being used in football. In a 1913 report of a match between Brighton and Bristol Rovers, The Daily Express wrote, “The crowd of 5,000 fairly gasped when Woodhouse missed a ‘sitter’.”

Early doors

The use of this phrase, as in “they’ll be looking to grab a goal early doors”, was a favourite of linguistically creative pundit Ron Atkinson. However, its origin long predates Big Ron.

At popular Victorian theatres, ‘early doors’ were special entrances at which patrons could pay extra to avoid the subsequent crush. The practice ended in the early 20th century, but the expression survived. The first man to use it in a football context was probably Brian Clough, who, speaking to The Observer in 1979 about his relationship with his players, said, “Early doors it was vital that they liked me.”

Plough a lone furrow

A target too big to miss for all but the most incompetent of strikers.

“Every Fulham fan was asking how Perry had missed such a barn-door chance.” The Daily Express, 1936.

A furrow is a trench in the ground dug for planting seeds or irrigation, and to plough a lone (or lonely) furrow is to work alone without any assistance, so this term has been applied to many an isolated football forward.

Perhaps the archetypal example is former Scotland striker Kenny Miller, who, The Herald recently reported, “spent much of his international career ploughing a lone furrow up front."

A case of handbags

Be it finger-pointing or swinging at thin air, footballers are often involved in ‘nothing’ altercations, like two bickering grannies swinging handbags in a Post Office queue. Initially, the term ‘handbags’ was used in football to describe a game gone soft. In 1971, newspapers complained that “something manly” had been lost, and that the game was “being played with handbags”.

However, after a tough-tackling match between Arsenal and Sheffield United, The Times commented: “If there were any handbags on the field last night, one or two of them might well have contained bricks.”

In 1985, Norwich manager Ken Brown responded to criticism of his side’s play after another rough game at Highbury. “The game is about competing, not about namby-pambies hitting people with handbags,” he said.

But it was Chelsea manager John Hollins who first used the term as we know it today. Commenting after a 1986 match, during which his defender Doug Rougvie had been sent off for clashing with Wimbledon’s John Fashanu, Hollins said: “It was a case of handbags at three paces and he was unlucky.”

Back to square one

The science of working the ball along the ground by means of the feet” (Football Annual, 1868), as opposed to drooling saliva down a chin.

“Dribbling, which infants and footballites alike are prone to.” - Penny Illustrated, 1875.

Accepted wisdom says that this phrase has its origins in a curious system used during the earliest days of radio commentary. Ahead of those games in the 1920s, the Radio Times would print a “listeners’ plan” that divided a football pitch into eight numbered sections. Commentators would refer to those numbers during a match in an attempt to give listeners a clear idea of where the ball was.

“That was a fine bit of play in section four,” a cut-glass voice might offer. It’s easy to imagine, watching a defender rolling the ball back to his goalkeeper, that one of these commentators could have coined the phrase “back to square one”. However, recordings of early commentaries contain only references to sections, never squares.

In fact, the first recorded use of “back to square one” didn’t occur until some 20 years after the commentary system had been scrapped. In 1952, the Economist Journal wrote that an author had “the problem of maintaining the interest of the reader who is always being sent back to square one in a sort of intellectual game of snakes and ladders”.

So the phrase almost certainly originates from board games rather than the beautiful game.

A sideways pass, as opposed to a non-spherical playing implement.

“The square ball is one of the best movements in football,” Fulham’s Eddie Lowe, The Daily Mirror, 1950.

Square pegs in round holes

A midfielder at centre-back, or a striker on the wing – they’re square pegs in round holes. This idiom can be found in newspaper reports going back to the 1850s, describing politicians, actors and military leaders. By the 1890s it was being used to describe rugby players.

“As a forward, Evans was a square peg in a round hole,” said one report. One of the first footballers to be labelled with the phrase was England winger Ron Flowers. In October 1959, after Wolves were beaten 5-1 by Spurs, The Times remarked: “Flowers, shanghaied from wing-half to defence, was a square peg in a round hole.”

Nutmeg

This spice-based idiom describes the skilful rolling of the ball between an opponent’s legs. In his 1968 book Shooting to the Top, Rodney Marsh wrote, “Three times I pushed the ball between the legs of the same full-back. This is the worst thing a forward can do to a defender because it makes him look foolish; and if, as I did, the forward then shouts ‘Nut Meg’ (the traditional taunt) the defender’s ego takes a knock.”

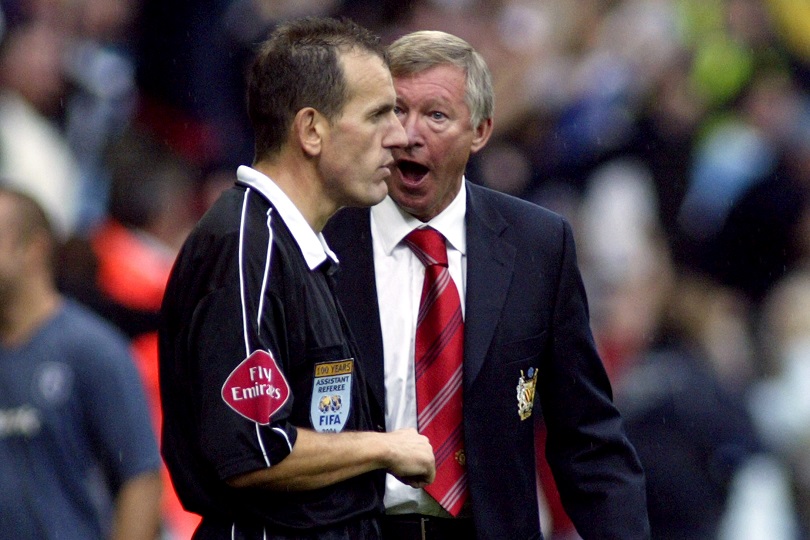

A close-quarters bawling out, patented by Sir Alex Ferguson.

“[Ferguson] grabbed me round the head and shook me. He’d just found out that it was me that started the hairdryer nickname!” - Mark Hughes, The Daily Mirror, 2006.

The phrase entered the mainstream around 1976, when The Times reported that the “nimble feet” of Spurs midfielder Glenn Hoddle had “nutmegged” West Ham’s Geoff Pike. As to its origin, one explanation of dubious legitimacy is that “nutmegs” was once a slang term for legs, or even testicles.

A more likely explanation is that in the Victorian era ‘nutmeg’ was a verb meaning to trick or deceive, derived from the underhand practice of diluting export consignments of nutmeg. Traders who were sold diluted consignments had been ‘nutmegged’, just like poor old Geoff Pike.

Potential banana skin

“Hereford away on a muddy pitch is a potential banana skin,” said Manchester United player-turned-pundit Paddy Crerand in The Daily Express in January 1990. Fortunately, his former club avoided an FA Cup fourth round slip-up – and went on to win the tournament.

Tricky cup ties are now habitually referred to as “potential banana skins”, despite the fact almost no one has slipped on a banana skin since the comedy pratfall was popularised by silent movie star Harold Lloyd in the 1910s. But, as The Times noted in 1971: “Logic has a way of slipping on a banana skin when it comes to football.”

Sick as a parrot

A refined or “educated” appendage, far superior to an uncouth right foot.

“He has a cultured left foot and is an excellent crosser of the ball.” - The Daily Mirror, 2000.

This expression has long been a stock phrase for post-defeat interviews, and was popularised in the ’70s by the likes of Bobby Robson, Brian Clough and John Bond. One of its first recorded uses was in 1974, when Robson told reporters Ipswich striker Trevor Whymark was “as sick as a parrot” after missing an easy chance.

But the phrase may have been around before then. Esteemed journalist Frank Keating claimed to have created it in the 1950s to irritate his sports editor at The Hereford Times, one ‘Polly’ Parrot. “When I invented that post-match loser’s phrase he’d violently excise it from my copy before hobbling to the editor’s room to demand my sacking,” said Keating.

And then there’s the tale of Tottenham’s parrot, presented to the club on a tour in 1908. With second-tier Arsenal controversially handed a spot in the newly expanded top-flight ahead of their relegated rivals, the bird promptly popped its clogs.

In fact, the etymology of the phrase can actually be traced all the way back to 1681, and a play by Aphra Behn called The False Count, which contains the line, “Lord, Madam, you are as melancholy as a sick Parrot.”

The old onion bag

An impressively neat change of direction. Still in use despite the fact that the sixpence coin was rendered obsolete by decimalisation in 1971.

"Oscar turned on a sixpence and put the ball under the bar.” - Gianluigi Buffon, 2012.

The goal net was invented in 1889 by civil engineer John Alexander Brodie, who also constructed the Mersey Tunnel. An onion bag, meanwhile, was a large net sack that was commonly used in Brodie’s time for carrying and storing more than just bulb vegetables.

The goal net/onion bag comparison was obvious, and the idiom soon entered football’s dictionary. However, by 1971, The Times was lamenting the loss of colourful football reportage along the likes of: “A rasping daisy cutter bulged the custodian’s onion bag.” In more recent times the ‘old onion bag’ idiom has returned to popular use, particularly in the US.

ESPN’s Tommy Smyth infuriated viewers by exclaiming after almost every single goal: “What a bulge of the old onion bag that was!” In 2007, one internet nut posted that he would “pay good money for someone to put a bullet in [Smyth’s] head.” Thankfully it was an idle threat, but it nevertheless prompted ESPN to launch a major security operation – of course codenamed Operation Onion Bag.

Win on paper

As every football fan knows, games aren’t won on paper. That fact was established during football’s formative years. In November 1890, The Birmingham Daily Post previewed a match between West Bromwich Albion and Aston Villa by saying: “On paper form, Albion should win, but paper form is not always correct.”

Put in a dazzlingly good performance.

In 1935, The Daily Mirror reported that England right-back George Male “played a ‘blinder’” in a win over Germany.

Villa won 3-0, which probably should have consigned the ‘win on paper’ idiom to the waste paper bin, but it’s still in use 123 years later.

Sold a dummy

A ‘dummy’ can be a counterfeit object, so to ‘sell a dummy’ is an act of deception. The term ‘dummy’ is used in bridge and whist, and has been used in rugby since the early 1900s. The 1907 Old International Rugby Guide describes “giving a dummy” as “feinting or pretending to pass”.

By the 1950s it was being used in a similar capacity in football. In 1956, the Daily Mirror raved about a performance from Spurs forward Tommy Harmer against Doncaster Rovers: “Coolly and deftly, Tom sold a dummy, sidestepped two eager Rovers, and slipped a slide-rule pass up to Johnny Brooks.”

The bottom-clenchingly tight final stages of a league campaign.

Coined by Sir Alex in 2003: “It’s squeaky-bum time, and we’ve got the experience now to cope.”

Gone pear-shaped

This idiom for when things go horribly awry is thought to have originated in the RAF as a description for an imperfect aerial manoeuvre. The phrase may have been introduced to football by the very publication you're reading now.

Describing Liverpool’s FA Cup defeat at Peterborough in the September 1995 issue of FourFourTwo, Trevor Rickwood wrote: “The day itself was one of those prize-winningly crappy days when everything went pear-shaped.” That’s just one example of this magazine’s invaluable contribution to the English language – indeed, FFT is cited 63 times in the Oxford English Dictionary.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2013 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!

Join The Club

Join The Club